“Clean, Healthy, and Full of Life!”

“Clean, Healthy, and Full of Life!”

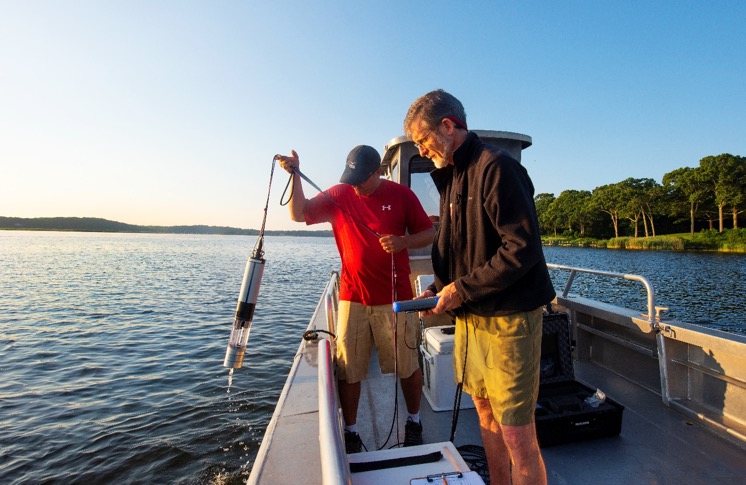

That’s Andy Fisk’s goal, and not just a dream, for the Connecticut River. Fisk, a patient, persistent, articulate scientist, is executive director of the Connecticut River Conservancy, a water-shed scale conservation organization based in Greenfield, Massachusetts. He can take water samples in the morning, and debate experts on water quality policy in the afternoon. Fisk is among those who comprehend the arduous journey from water testing to legislation based on those tests, with a lag time of 5, 10 or even 15 years. Good, sound, effective water policy development must therefore necessarily survive multi-generations of elected officials in governors’ mansions as well as the White House.

A brief history of the environmental movement at the federal level bears repeating. Public opinion regarding air and water pollution was largely shaped by Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, published in 1962, and sensationalized catastrophes such as the 1969 fire on the Cuyahoga River in Ohio. In 1970, President Richard Nixon brought the Environmental Protection Agency into being with William Ruckleshaus as its first head. Ruckleshaus noted that, “public opinion remains absolutely essential for anything to be done on behalf of the environment.”

The Clean Water Act of 1972 brought voluntary standards for discharges of pollutants into navigable inland waterways. President Jimmy Carter’s EPA administrator, Douglas M. Costle, who had also led the study in the late 1960s that recommended the creation of the EPA and in 1975 was Connecticut’s Commissioner of Environmental Protection, championed the Clean Water Act (as amended) of 1977. This act outlawed the use of any pipe or man-made ditch for discharges into navigable waters. The law also required industry to meet “best technological standards” for specified pollutants with a deadline for compliance of 1984. “Voluntary compliance” was replaced with “mandatory compliance with penalties.”

The die was cast. Industries, farms and individuals made the necessary investments. The Connecticut River rose from a Class D (basically, dirty and unsanitary) River to a Class B River, which it is today.