“Sunset Over the Connecticut River”

Photo by Susanne Hall

Editor’s Log: Island Solitude

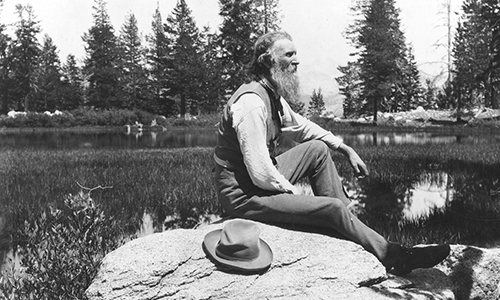

“Come to the woods, for here there is rest,” wrote John Muir, the pioneering environmental activist and writer. “There is no repose like that of the green deep woods.” Few knew the healing power of nature better than Muir (1838–1914), whose deep connection with the outdoors was forged through a convalescence.

- Page 2 of 2

- 1

- 2