This article appears in the Winter 2025 issue

This article appears in the Winter 2025 issue

Chapter 20: Leyland Saves the Day—Twice

Me and Ray are expert ferrymen, it’s true, but we’re experts with small ferries that shuttle people, animals, and the mail across the Connecticut River between Saybrook and Lyme. When we signed up with the Union Army, the recruiting officer asked if we had any special abilities, and of course we said we were experienced ferrymen and heirs to the family ferry business. We maybe over-talked the expert part of our years of experience, especially the part about ferrying being in our blood, being first cousins preceded by four generations of ferrymen. We really laid it on.

I guess all that bragging worked, because the Union Army jumped at the chance to put us in charge of a broken-down, old, steam ferry and issued us orders to move arms, ammunition, supplies, and soldiers up and down the Rappahannock River. This river was a high danger zone with Union forces on one bank and Confederate forces on the other, each side wanting to control it. After we got here, we learned that three ferries before us got blown up or sunk. I guess we asked for it.

There’s one good thing. Turns out that Leyland, my prisoner, really does know how to operate a steam ferry like the Saybrook, seeing as how he had a paid job shoveling coal on a paddle-wheel steam ferry that ran up and down the Mississippi River before he signed up with the Confederate Army.

The Union soldiers that loaded up the ferry by torchlight this morning hid several long wooden ammo boxes under sacks of dried beans, a big gunny sack of oats, some chicken feed, and bales of hay. Also onboard were a half dozen crates carrying live laying hens, one milk cow, and a fresh load of coal—enough supplies to keep a cavalry unit of men and horses fed for a week or more and enough coal to keep the Saybrook’s boiler going for two or three days.

I raised anchor before dawn, my favorite time of day, first light, and was just ready to push away from the dock when I heard—

“Fire in the hole!”

I shot a look at Ray. “That’s Leyland,” I said.

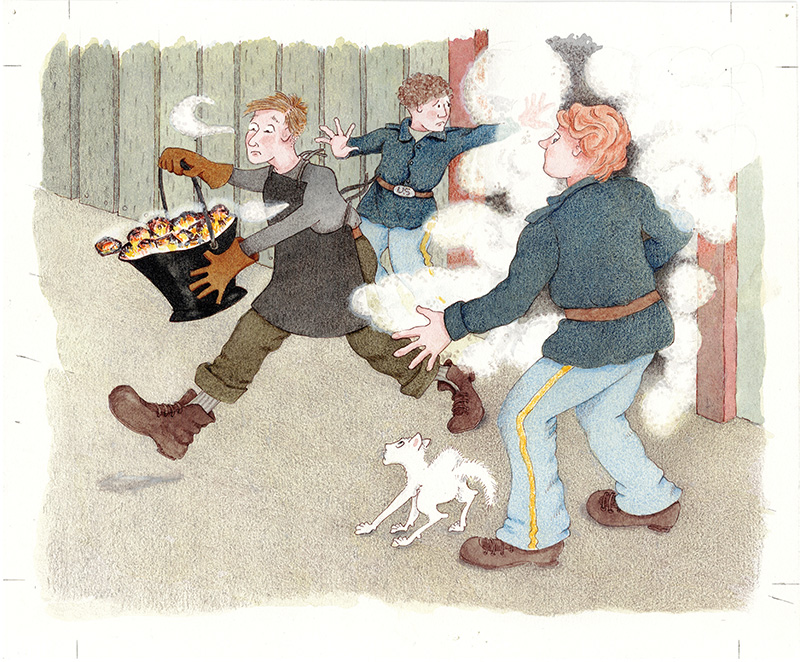

Ray and me got down to the main deck just as Leyland ran out of the engine room wearing his heavy canvas apron and big leather gloves and holding a metal coal hod full of red-hot coals in front of him.

“Get back!” he shouted. “Might explode! Keep away from me.”

Leyland ran for the edge of the deck and tossed the coal hod off the starboard side, into the river. As soon as that pail hit the water there were two explosions, busting it wide open.

“There goes a perfectly good coal hod,” Ray said.

Boom! Another explosion came from behind us in the engine room.

“I’ll get the hose!” I shouted.

Ray worked the pump, and I let the stream of water lead my way into the engine room. I couldn’t see a thing. Thick smoke burned my eyes and made me choke.

“Don’t want this smoke in your lungs!” Leyland shouted. “Carbon monoxide, heavy metals, bad stuff!”

Once the smoke cleared out of the engine room, we got a chance to assess the damage. The coal shovel was lying on floor, the iron door of the firebox hung by one bolt, and red-hot bits of coal and embers were scattered all over the engine room, sizzling, hissing, and popping in puddles of water.

Leyland quickly put out some flames on top of the footlocker.

“Could’ve burned up my uniform,” Leyland said.

“Almost got blown to kingdom come, and haven’t left the dock yet,” I said.

“Sabotage,” Leyland said, nodding. “Coal torpedo. Confederate Army trick. Probably hidden in that new load of coal we took on this morning. I spotted a fake piece of coal only after I had already shoveled a whole lot of it into the firebox. I shoveled that coal out as fast as I could and into the coal hod.” He lifted the broken firebox door. “Obviously, missed one.”

“Leyland? How is it you know so much about coal torpedoes?” I asked.

He handed me an unexploded one and said, “Recruiter knew I worked on a ferry shoveling coal, so he put me in charge of making these things. Keep this so you’ll know what they look like. Meanwhile I’ve got to comb through that whole new load of coal in case there’s more. Didn’t count on being a prisoner of the Union Army and have the chance of my own torpedo blowing up in my face.”

“Do unto others,” I said, “as you would have them do unto you.”

“Yeah,” Leyland said. “Bad deeds will come back to bite ya.”

We finally got underway, the Saybrook chugged along, heading south toward Fredericksburg with our first delivery. The surface of the river looked calm enough, but I was fighting a strong current underneath. I knew about currents from all our years on the Connecticut River, which takes a mariner to school every time he sets sail.

THUMP! Did something just ram into the Saybrook? We were all a little jumpy after the coal torpedo incident. Probably debris in the river, I told myself.

Minutes later, another THUMP!, then, shouts—a man’s voice. No, two men?

Another shout, “Put down them ropes and stand fast, Yank!”

I pushed the curtain back, looked down to the main deck, and saw a dinghy in the water banging against the starboard side. A Confederate soldier was holding his rifle aimed directly at Ray’s navel. “Let’s get ourselves up to the wheelhouse,” I heard him say.

I turned to grab my Springfield standing in the corner behind me and found myself facing a different Johnny Reb, not three feet away from me, now in the wheelhouse and with a rifle aimed at the floor right next to my right foot.

“Just keep both them hands on the helm, and your eyes dead ahead, Yank,” he said. Then, picking up my logbook, he started reading my latest entry aloud. “Bulk food supplies and animals to Fredericksburg area…sounds innocent enough,” he said, putting the logbook down. “Only, somebody’s been hauling ammunition on this river, right under our noses, and I’m guessing it might be y’all.”

I wanted to tell him it couldn’t possibly be us since this was only our first day running supplies on this river, but I said nothing.

Ray pushed the curtain aside and was shoved into the wheelhouse by the business end of an Enfield rifle musket.

The second Reb swung the Enfield back and forth between Ray and me and said, “You hold this floating wreck of a boat nice and steady, while your Yank pal and me go back down to the cargo bay and take a look to see what you really got stowed in there.”

I felt sweat in the palms of my hands and a wave of nausea wash over me—someone could actually get shot and killed today, and that someone could be Ray or me. All these feelings and thoughts rushed around in my stomach and my brain when a third Confederate soldier flung the curtain aside and stomped onto my bridge, shouting—“What, in the name of Stonewall Jackson is going on here!”

It was Leyland, struggling to buckle his pants.

“A soldier can’t enjoy a peaceful moment in the outhouse,” Leyland said, “that he’s disturbed by uninvited guests on his boat.”

“Your boat?” Reb one asked.

“You heard me, soldier. It’s my boat now,” Leyland said, shooing the soldiers out of the wheelhouse like he was swatting at flies, “Now, y’all can just step back outside this curtain and leave my pilot to his business.”

Reb two piped up. “Your pilot?”

“This boat ain’t flyin’ no colors. How we supposed to know?” Reb one protested.

“What you got in that cargo bay, huh?” Reb two asked.

“Somethin’ don’t smell exactly right here,” Reb one chimed in, followed by Reb two. “Where’s your gun? You one of us, but you ain’t got no gun?”

“Y’all are beginning to irritate me,” Leyland said, “These two Billy Yanks,” he points to me and Ray, “are my prisoners, see? Mine, not yours.”

“They sure don’t act like prisoners. Why ain’t they tied up?”

“Now, listen, friend,” Leyland said. “How dumb would I have to be to tie the hands of a pilot of this boat?”

“What about this other guy?” Reb two said, pointing his gun at Ray.

“He’s the second pilot. They trade off,” Leyland said. “They both got parole papers, so I got to keep them from harm, but they’re true ferrymen, so I got them working for me since I confiscated this boat. Ain’t that the truth, JJ?”

“Yeah,” I said, acting annoyed. “It’s true all right.”

“Yes…what?”

“Sir!” I barked. “Yes, SIR.”

The two intruders lowered their rifles. One said, “Okay, friend. You can take us on a tour of your cargo bay.”

I watched as Leyland, Ray, and the two Johnny Rebs climbed back down to the main deck, pushed the big barn door open, and disappeared into the cargo bay. They came out after a few minutes. Leyland played boat captain until he made sure the two Rebs were back in their dinghy, oars in hands, and headed back upriver to their camp.

“Couldn’t stop them,” Leyland said, “when they helped themselves to two laying hens.”

“I noticed,” I said. “Small price.”

I continued piloting downriver. I breathed a sigh of relief when I sighted a dock ahead, and three Union soldiers waiting for us. One jumped onto the Saybrook’s port side and tossed the mooring lines to the men on the dock who secured us to the pilings.

“You made it,” a soldier said. “Any trouble?”

“Trouble?” I laughed. “I’ve got a whole new definition of a good day. I’ve had the soldiers’ basic good day when I’m not shot dead by a Johnny Reb. Now, it’s a good day when the Saybrook doesn’t sink to the bottom of the Rappahannock because a coal torpedo blew the firebox out through her portside.”

Leslie Tryon is an award-winning author-illustrator of children’s books (Simon & Schuster, publisher). Five generations of Tryon’s family served as ferrymen on the Connecticut River between Old Saybrook and Old Lyme, Connecticut, and many of those men were named JJ.

Historical Notes:

The Rappahannock River

A critical transportation route between the Union and Confederate capitols, control of the Rappahannock River changed hands several times during the war. The battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Rappahannock Station were fought along its banks.

Coal Torpedoes

During the Civil War, bombs and other explosives were called torpedoes. A coal torpedo was a bomb made to look like a piece of coal. A hollow container was filled with gunpowder and coated with coal dust. It could be mixed in with real coal and unknowingly shoveled into the firebox of a ship or train. Secret agents in the Confederacy used these to sabotage Union transportation.

PBS Learning Media

Rifles carried during the Civil War

Union infantry carried the Springfield 1861 rifle; Confederate infantry carried the Enfield rifle musket. The Enfield had a slight advantage over the Springfield as it was a bit more accurate at long distances.