This article appears in the Winter 2025 issue

This article appears in the Winter 2025 issue

The Terrestrial Hatch

The Terrestrial Hatch

Story and Photos by Ed Mitchell

In the short, dark days of winter, we find ourselves thinking back to the angling season just past, fondly remembering our time on the water. For many anglers the pinnacle of those memories is dry fly fishing, an exciting, challenging part of our sport. And the source of that fishing centers around caddis and mayfly hatches.

As essential as those hatches are, they aren’t always predictable, varying in timing and intensity from year to year, tapering off dramatically in the warmer months. But there is another source of dry fly fishing—one often overlooked; one that provides dry fly action in summer and early fall when caddis and mayfly hatches wane; one that goes on all day long, fooling the biggest, wariest trout—yet one that remains a mystery to many anglers.

Stream edges with lush vegetation are productive for terrestrial flies that resemble ants, beetles, grasshoppers, and crickets.

Figured it out? You’re right, its terrestrial insects, land-based bugs attracted streamside for both food and water. Occasionally they slip, flip, flop, or fall into the stream. Once afloat, trout love munching on them, gobbling up ants, beetles, caterpillars, crickets, grasshoppers, inch worms, spiders, and a host of other creepy crawlers as if they were candy. Yes, this type of dry fly fishing is unlike a caddis or mayfly hatch. Don’t expect squadrons of insects floating down stream. No, you’ll be fishing “blind,” searching the best-looking water where famished trout await your terrestrial fly.

Where and When: The prime time of year for terrestrial insects begins in mid-June and runs through August and September, lasting until the first frost of the year. Action occurs at any time of day, although early morning and late afternoon are often best. Weather is rarely a factor, although a breeze or rain pushes many terrestrials into the stream. Focus your fishing along lush grassy banks, bushy shorelines, and where tree limbs dangle over the stream. Those conditions all deliver insects to the water. Best yet is a fallen tree, one extending out into the current. Its limbs often host a great many insects, making this location an angling gold mine. And be alert wherever a river goes under a low-lying bridge, or wanders along a field. They’re all productive.

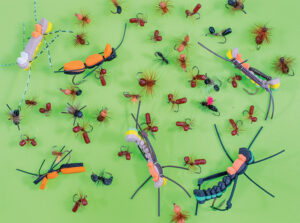

Fly Patterns

We can’t cover all the terrestrial fly patterns available here, but allow me to point out some of the popular ones: ants, beetles, “Chernobyl” ants, and grasshoppers and crickets. And since ants are the most well-known and widespread of these terrestrial insects, let’s start there.

Common Ants. Ants range from large carpenter ants down to diminutive red and brown ones. To cover this range, you should have ant patterns from hook size 10# down to size 18#. The overwhelming majority of the existing ant patterns are tied with simple foam bodies and a turn or two of hackle. And black ant flies are the most popular. Still, I urge you to carry red ant flies, especially in small sizes, 16# on down. Frequently called cinnamon ants, they are absolutely deadly. I’ve seen them pull cautious trout up off the bottom even in hyaline waters.

Ants and “Chernobyl” ant flies.

Chernobyl Ants. Around 25 years ago out on Utah’s Green River, a new type of terrestrial fly pattern was born: the Chernobyl ant. The name is a prank. These ugly flies look more like a prop from Star Wars than any ant. But as the gag goes, supposedly these flies mimicked an insect mutated by nuclear radiation—hence the reference to Chernobyl. Upwards of 1.5 inches long, the original patterns were large, and meant to be a meal too big for a trout to pass up. Tied on 2x long hooks in sizes from 6# down to size 10#, the top of the hook shank is a layered pile of colored foam sporting rubber legs. Many anglers laughed at these monstrosities—myself included. But I was wrong. Chernobyl ants work well, although today on eastern water where fish may be warier, smaller Chernobyl ants are growing in popularity tied down to size 14#.

Beetles: There are several types of beetles common along riverbanks. Despite the variety, a basic fly is all you need. Years ago, I saw a beetle fly that was just a coffee bean with a hook glued to the flat bottom. True story. Like ant flies, the vast majority of beetle flies incorporate a black foam body. Some patterns go a step or two further by adding legs or a piece of bright floss topside to make the fly easier to see on the water. It’s a helpful touch. Beetle flies are commonly tied up in sizes 10# to 16#. But in those years when cicadas are around, big beetle flies in size 6# are appropriate.

Grasshoppers & Crickets: Grasshopper flies are legendary for inducing wild strikes. And it’s totally understandable. Compared to an ant or beetle, a grasshopper is a belly buster trout can’t ignore. But there is a downside. Grasshoppers are far fewer in number, with their abundance tending to go through cycles. And hoppers are not as extensive or numerous as ants and beetles, usually only found where streams run through grassy meadows, pastures, and agricultural lands. And weather plays a role too. A warm, dry day with a bit of wind is the absolute best.

Beetle, grasshopper, and cricket flies.

Over the years hopper flies have been made with a variety of material from deer hair to balsa and cork. But here, too, foam has largely taken over, as it is cheap and floats well. Color schemes include green, yellow, and brown. Size 8# or 10# 2x long hooks are the norm, with small hoppers tied on a size 12# hook. Forget dropping these flies gently on the water. Go ahead and plop them down near the bank, the sound brings hungry trout a-running. And give the fly a twitch too. By the way, an all-black hopper pattern makes an excellent cricket imitation.

Now for the famous “hopper-dropper” combo. A hopper fly is big enough to support a smaller fly dangling underneath. For that matter, some Chernobyl ants can too. You make this rig by simply tying a short piece of monofilament off the hook bend to which you attach a small fly, typically a nymph. Obviously, this tactic offers the trout a choice. Big fly above, small one below.

Ed Mitchell is the author of four books on fly-fishing and has written for many magazines. He has over 50 years of experience in both fresh and saltwater fly-fishing.