This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue

This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue

It Turns Out,

Gardening is Also Good for You

How much time does it take for people to get a dose of nature high enough to say they feel healthy and have a strong sense of well-being?

Precisely 120 minutes—and that’s either all at once or over the course of one week.

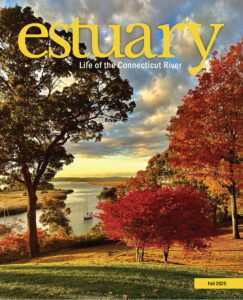

A walk in nature can lower blood pressure. Research from Japan has found that trees and plants emit “phytoncides”—aromatic compounds—that, like aromatherapy, lower blood pressure by subduing the body’s fight-or-flight stress response. Image Credit: Judy Preston.

This was the conclusion of a robust 2019 European scientific study of 20,000 people representing different occupations, ethnicities, and economic circumstances and those with chronic illnesses and disabilities. Plenty of other studies have come to similar conclusions: ninety minutes in a natural setting, for example, has been shown to reduce the tendency to brood, which is associated with both depression and anxiety. Natural environments have also been shown to reduce feelings of isolation and aggression in psychiatric patients.

If you are a gardener, you likely know that being surrounded by nature and growing things just feels good. Gardening is time spent in nature, and the benefits of gardens for human health are increasingly well documented. These benefits include lower blood pressure and stress hormone levels, enhanced immune system function, reduced anxiety, and improved mood.

Audubon’s Forest Classroom integrates the outdoor classroom with rigorous academic concepts, conservation-based themes, and connection with nature. Image Credit: Emily Kaplita, Audubon Vermont.

On some level the benefits of nature have been understood, intuitively, for a long time. The use of “hospital gardens” date back to Hippocrates. Sanitariums in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were places where people could go to heal. Spending time in sunlight and the fresh air of the country were understood to be important for the treatment of respiratory conditions. Even the evolution of our country’s national parks recognized the healing powers of nature for both mind and body.

My own (and many others’) interest in the topic was piqued with the publication of Richard Louv’s 2005 book, Last Child in the Woods. In it he coined the phrase “Nature Deficit Disorder” that handily played on “Attention Deficit Disorder,” a term that was rapidly stoking the public’s fear of childhood inattention.

Louv highlighted the human costs of alienation from nature, citing accelerating social and technological changes in society and the decline of our ability to understand and therefore be good stewards of the natural world. Healthcare experts echoed concern, citing an “epidemic of inactivity” and the loss of independent play in children. Despite all the negatives, Louv emphasized the benefits that could be gained from the connection to nature—especially nearby nature.

But this idea was not new. In the early 1980s, the Japanese introduced mindful strolling in the woods to treat depression as the practice of “forest bathing.” In his 1986 book, Biophilia, biologist Edward O. Wilson argued that “our natural affinity for life—biophilia—is the very essence of our humanity and binds us to all other living species.”

The naturalistic landscaping at this shoreline health clinic in Westbrook, CT, echoes the building’s “interiorscape”; both enhance the visitor and patient experience. Image Credit: Judy Preston.

In the last four decades, many studies have investigated the physical, mental, and emotional benefits of exposure to nature. What started as a topic with little interest from academia has come to flourish through research and clinical trials that are paving the way to incorporate nature benefits into health applications.

The benefits of nature have also been applied to buildings. Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification, introduced in 1998, influences the design and management of a building to protect the environment, while also enhancing the human experience of it (referred to as its “interiorscape”). One example is healing gardens, such as the one at Yale Health’s Smilow Cancer Hospital in New Haven. These specialized gardens have become increasingly common as nature-based refuges for patients dealing with life-threatening conditions, and include the therapeutic application of plants.

Gardeners already note that the annual dormancy and rejuvenation of plants is what helps to set our own biological clock. There is something reassuring and comforting—especially in New England—to being able to mark the passage of time through the spring burst of green after the winter and the extraordinary beauty that marks the end of the growing year with autumn foliage. In fact, fall is my favorite time of year—for walks, for the garden wrap up, and for the prospect of sitting at the fireplace pouring through seed catalogues and making notes about aspirations for next year’s garden. There is no “bad” season in nature, and knowing that we can benefit—in many ways—from what surrounds us outside is another reason to love gardening.

Judy Preston is a local ecologist active in the Connecticut River estuary.