This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue

This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue

Chapter 19: Leyland

The Union camp and our ferry assignment—a steamboat on the Rappahannock River—was just a few hundred yards from where Ray and I jumped off the train.

Ray was fifteen or so yards ahead of me as we ran across the field when I tripped and fell into a foxhole. By the time Ray doubled back to find me, a Confederate soldier had shot him in the arm. I fired two shots at that Confederate soldier, just grazing his forehead but injuring his leg; he dropped to the ground, so I took his gun away. When I realized he couldn’t run away I captured him and took him prisoner for the Union—which seemed like a good idea at the time. My prisoner—blood-soaked pant leg and blood running down his face—couldn’t walk, so Ray and me had to pick him up and give him two shoulders to lean on, supporting him the rest of the way into camp.

As a lieutenant approached us, we saluted while my prisoner hung on, “Reporting for ferry duty, Lieutenant. Sir, I’m JJ, and this is my cousin Ray. We’re your ferrymen.”

“And this?” the lieutenant said pointing to the bloodied Confederate soldier hanging between us.

“Captured and taken as prisoner for the Union, sir,” I said proudly.

“Name’s Leyland,” my prisoner said.

“And what in the name of Ulysses S. Grant possessed you to take this man prisoner…your name—JJ, was it?”

“Yes, sir, that’s my name. Just the letters, J and J. Stands for Jeremiah Jedidiah, which is too long, so everyone just calls me JJ.”

The lieutenant folded his arms across his chest, glanced toward the camp and back at us. “As you can see, JJ, we’re a temporary installation here, just a few hand-picked men, a boatbuilder, an engineer, a medic, a cook, and a collection of what I hope are the right tools to get that ferry operational. We are not equipped to house, feed, or hold a prisoner.”

“Then, what do I do with him, sir?”

“Name’s Leyland.”

“The military hasn’t set up an exchange program yet, so we can’t swap him for a Union prisoner. There isn’t a prison within a day’s ride, so we’re left with just one option. As soon as we get him patched up, I’ll issue his parole pass, and he’ll be on his way out of here and out of our hair.”

“Parole pass?” Leyland said.

“You’ll sign a piece of paper promising not to return to any fighting unit and take up arms against the Union Army. A parole pass gets you safe passage home, that’s it.”

“Hey, I was born and raised alongside the Mississippi River,” Leyland said, “Hundreds of steamboats on that river, I worked on one, shoveling coal. I know steamboats.”

“Do I understand—Leyland?”

“Yes, sir. Leyland.”

“Are you saying you’ll switch sides and fight with the Union?”

“No, sir. I got no allegiance to Jefferson Davis or Abraham Lincoln. I signed up ’cause they promised me a regular paycheck.”

“So, you don’t want a parole pass?”

“No, sir. I’ll take that pass and go home, like you said. I just figure, since I’m in no condition to travel on foot right now, maybe I can help with that steamboat you got there, while my leg and my head are scabbing up. I can stay a few days and help y’all.”

The lieutenant gave us each a long weary look, smiled, and walked away.

A cavalry horse with a freshly bandaged left rear fetlock was tied up outside the medic’s tent. His rider—an officer—walked out of the tent as we were walking in. He stopped, turned, and looked at the Confederate soldier hanging between us. “What’s this?” he asked.

“Confederate prisoner, sir,” I said.

“Prisoner? What on earth will you do with him here, in this camp?” he said, then to no one as he walked on, “But, that’s not my problem.”

“No, sir, not your problem, sir,” I said, and we continued into the tent.

Inside the tent a soldier, standing at a porcelain bowl, his sleeves rolled up past his elbows, scrubbed his hands. He reached for a towel, dried his hands and forearms, and said, “Now, what can I do for you fellows?

“Two injured men,” I said.

“I got shot here, in the arm,” Ray said.

“This one’s a prisoner. I shot him in the leg and grazed him in the head.”

“Hey, wait a minute,” Leyland said, “that horse. You’re a horse doctor.”

“I prefer the term, Veterinary Sargeant; only here, in this Army, in this tent, until my cavalry assignment gets here, I’m the medic. I was sent here because the lieutenant got word there wasn’t a veterinarian within fifty miles of here. I’m what you got, soldier. I’ll fix you up just fine,” he smiled, “just like I stitched up that Morgan pony you saw outside this tent.”

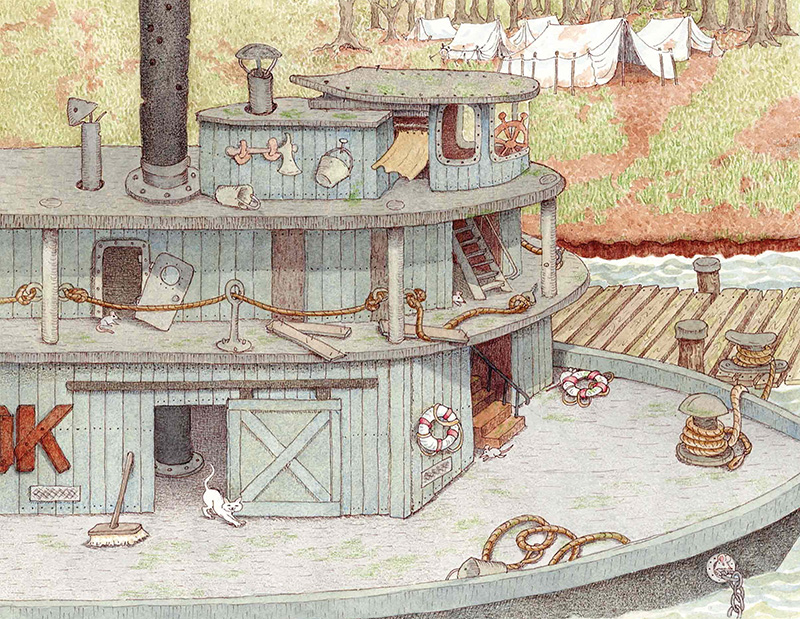

It was midday by the time Ray and Leyland got stitched up, and we were all able to meet on the dock, tools in hand, ready to check out our new home-away-from-home, a steamboat. The lieutenant gave us a briefing and said we were camped in a place called Tappahannock, and what he learned was that this steamboat had been abandoned by the owner right after the war began. Confederates had a water battery just a few miles south of here, cannons and such, which, I can tell you, would be enough to scare this ferryman off the river.

Peg, a boat-builder from New Bedford, introduced himself and told us how two days earlier he dove into the river, swam under the steamboat and checked the hull. “Fore to aft,” he said, “the timber’s not in the best shape, soft in spots, but not as bad as I expected it to be for a boat that hasn’t been dry-docked in a couple of years. No leaks inside, either. Being that this river is a tidal estuary, that freshwater changing places with the salt water every day has protected the wood. Patches of moss everywhere, and it looks like somebody’s been using the smokestack for target practice.”

Liam, the engineer, reported on the condition of the engine room. “Got a whole clan of mice living in the coal bunker, must be several generations in here. Cute little critters. That white cat hasn’t been doing his job. If I can get my hands on a bucket, I’ll relocate the mice to the woods up there, then we can get a fire going.”

“What about fuel?” I asked.

“Got a coal delivery a couple of days ago; it’s in the supply tent,” the lieutenant said.

“She sure does stink,” Ray said. “That main transport area is like a boxcar, just a big empty space with a few slits cut in the wall for air to pass through and drain holes in the floor. This whole boat has a serious lack of windows.”

“I can tell you this,” Leyland said, “this riverboat was never meant for ladies and gentlemen, fancy meals, player pianos, or gamblers like the ones where I shoveled coal.”

We had plenty to talk about that night at supper as we arranged our camp stools in a circle and enjoyed our bean soup and hardtack. Even the cat came around, looking for handouts, I suppose.

Liam, the engineer, told us how he upended the bucket of mice near the stand of trees and how they all huddled together not knowing what to do with all that bright sunlight and wide-open spaces, until a brave one explored the base of a tree and found a hole under an old dried-up root. “He made some kind of a squeak that they all seemed to understand, and they dashed into that hole like it was a foxhole and they were being fired on by nature.”

I read the last entry from a logbook I found in the wheelhouse about how on June 7, 1860, eight cattle, four goats, and a half-dozen pigs were transported to Rappahannock Station.

“No wonder it smells like a barn,” Ray said.

“I gotta put in a good word for your man Peg,” Leyland said. “He fashioned this here crutch for me.” Then he turned to Peg and said, “How’d y’all get a name like Peg, anyway?”

“I don’t use nails if I can avoid it. When I build a boat, I use wood pegs. I plan to make some pegs for the roof on your wheelhouse, JJ.”

I studied my prisoner, the way he fit right in with everyone, sitting there in his grey Confederate uniform with the gold stripe up the leg, and the rest of us wearing Union blue. He seemed like a regular fellow, when only this morning we fired at each other with intentions to kill, which is the job of a soldier, I guess. Paid killers, that’s what we are. Doesn’t make sense to me.

“What do you want to call her, JJ?” Peg asked, “I’ll craft a sign out of some wood scraps I salvaged from damaged siding inside the passenger space. It’ll hold you over until you get your hands on some paint and a paintbrush.”

I didn’t have to ponder at all—I was ready for that question. “Saybrook,” I said. “That’s where Ray and me come from, and just like this old steamboat, Saybrook is a hard-working little village that sits alongside the Connecticut River, where every house has at least one family of mice and a lazy cat, moss grows on everything—it’ll grow on you if you stand still too long. Someone’s always replacing rotting planks on a house or a dock or a boat, and the air stinks to high heaven twice a day at low tide. That’s what we’ll call her—Saybrook.”

Leslie Tryon is an award-winning author-illustrator of children’s books (Simon & Schuster, publisher). Five generations of Tryon’s family served as ferrymen on the Connecticut River between Old Saybrook and Old Lyme, Connecticut, and many of those men were named JJ.

Historical Note

Armies of the North and South found themselves having to deal with thousands of prisoners of war. As the number of prisoners increased, camps were built specifically as prisons, including the most infamous, Andersonville. Both armies chose to parole prisoners as the lesser evil. Captured men were conditionally released on parole if they promised not to return to battle. A soldier under parole would sometimes stay on and work with their captors, but could not bear arms.

–National Park Service—

An introduction to Civil War Prisons

In 1863, the United States War Department ordered that each cavalry regiment have a “Veterinary Surgeon.” At $75 per month, these men enjoyed more than four times the pay that the “Veterinary Sergeants” had received.

–National Museum of Civil War Medicine