This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue

This article appears in the Fall 2025 issue

The Mount Holyoke Range’s unusual east-west orientation, geologic formations, and

The Mount Holyoke Range’s unusual east-west orientation, geologic formations, and

extensive conserved forests provide critical habitat for wildlife. Image Credit: Jamie Malcolm-Brown

Addressing the Biodiversity Crisis

in the Connecticut River Valley

By Kari Blood

One of the reasons many people love living in the Connecticut River valley is the ability to observe wildlife in the landscape around them. In Western Massachusetts, where Kestrel Land Trust’s headquarters is nestled at the foot of the iconic Mount Holyoke Range, we see migrating warblers flitting around the treetops in spring, resident beavers engineering the water flow around the pond outside our office, and the occasional bobcat slinking past the window. The headwaters of the Fort River, a focus area for the Silvio O. Conte National Wildlife Refuge, are located in these hills. The combination of protected forest and water provides ample habitat for many species.

Yet, wildlife sightings in the valley will become increasingly rare if we humans don’t take bold steps to slow the loss of species in our region and around the world. In recent years, scientists have been sounding the alarm not only about the climate crisis but also about the inextricably linked “biodiversity crisis.” Birds, insects, fish, mammals, and even plants are losing ground in terms of their populations, and they’re literally losing ground as their habitats are developed, polluted, fragmented, and destroyed.

The term biodiversity, a term that’s often used but rarely defined, refers to the variety of all types of life in the natural world including plants, animals, fungi, algae, and even microorganisms like bacteria. Biodiversity is a key indicator of the health and resilience of an ecosystem: the web of habitats, plants, animals, and all other living things in a given location. Measuring biodiversity at its most basic level means counting the number of different species that share a certain home region, but it also includes how many of each species and how those quantities are related to each other. It also includes measures of available habitat.

The Living Planet Report by the World Wildlife Federation studies trends in global biodiversity, and in 2024 it revealed an average decline of a staggering 73 percent in overall species populations worldwide since 1970. Researchers have also recently found that we have lost more than 25 percent of all North American birds in the last fifty years. In Massachusetts, there are more than 453 wildlife species listed under the MA Endangered Species Act, and that number could easily grow.

The gray fox is a common but secretive species that relies on forest habitat. Image Credit: Mark Lindhult.

While there are multiple factors that contribute to any particular species’ decline—such as pesticide use, widespread disease, competition from invasive species, or overharvesting by humans—habitat loss is often a significant factor. Human development of buildings and roads, intensive land use like industrial agriculture, and resource extraction such as mining and oil drilling are the main drivers of this loss. One of the best ways to address the biodiversity crisis, therefore, is by protecting the lands and waters that provide the homes, food sources, breeding grounds, and conditions that species need to thrive. Fortunately, conserving land and water for habitat is also a natural solution to climate change, which also threatens biodiversity.

Traditional efforts to conserve biodiversity tend to focus on well-known species that are in decline, like the blue spotted salamander or timber rattlesnake. National and state governments list species as being endangered, threatened, or vulnerable, or similar terms, and those designations trigger various levels of legal protection to reduce harmful human impacts and to encourage human actions to help species populations to recover. This system can work well if agencies, corporations, governments, and individuals follow the rules. But it may not be enough.

To conserve the entire interdependent web of life, we also need to focus on species that are common now, to reduce the chances they’ll need to be listed as threatened or endangered in the future. This more holistic approach of keeping common species—like black bear—common, requires protecting entire habitats, which can benefit whole suites of other species.

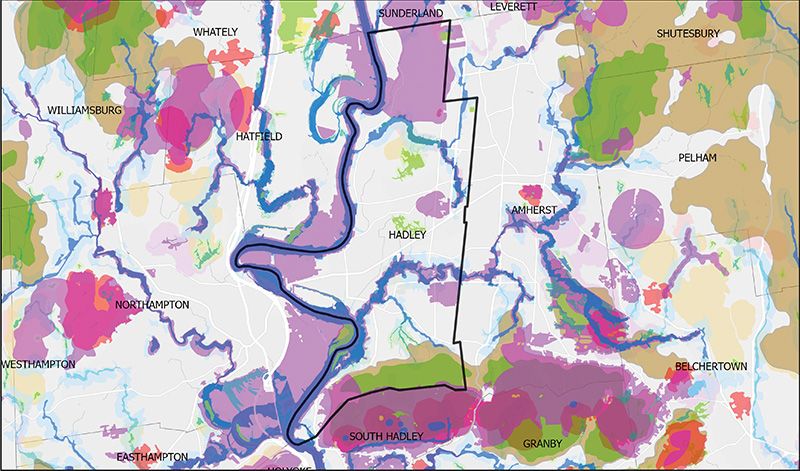

Regional nonprofit land trusts like Kestrel Land Trust play a critical role in protecting biodiversity through conservation efforts guided by up-to-date scientific tools that identify the most important lands for both common wildlife and threatened species. One of the tools we use in Massachusetts is called BioMap. Produced by MassWildlife and The Nature Conservancy, BioMap uses innovative mapping capabilities and on-the-ground scientific data about species locations to deliver an interactive map that identifies areas with valuable habitat for conservation efforts.

Kestrel Land Trust headquarters at the base of the Mount Holyoke Range overlooks Plum Brook Pond within the Town of Amherst’s Sweet Alice Conservation Area. Image Credit: Kestrel Land Trust.

BioMap sorts lands according to two primary categories: Core Habitat and Critical Natural Landscape. Core Habitat identifies areas that are vital to sustain rare species, exemplary natural communities, and climate-resilient ecosystems. Critical Natural Landscape identifies large landscape blocks that are minimally impacted by development, and lands that provide a buffer around core habitats. These lands safeguard habitat connections between core habitat areas and improve resilience, that is, the ability for the land to withstand disturbances while sustaining the health of its plant and animal communities.

Kestrel works with landowners to assess their lands for conservation. Our team relies on BioMap to determine whether the land under assessment is likely to provide habitat for threatened or endangered species or provide a buffer around those areas. We also look for undeveloped land connections between these higher priority habitats, which can provide critical corridors for wildlife to move across the landscape as changes in weather patterns modify their usual range. The detailed analysis often highlights forests as the priority, but areas of farmland also may show high value for various types of wildlife.

Bigger Is Better for Biodiversity

Western Massachusetts forests are a part of the Northern Appalachian ecosystem, which is among the largest remaining areas of intact ecologically significant forest in the world. These lands provide vital pathways for wildlife to migrate.

Kestrel is part of two regional conservation partnerships working to protect these lands. One is the Berkshire Wildlife Linkage within the Staying Connected Initiative’s 1.58 million acres of forested landscape from the Green Mountains in Vermont to the Hudson Highlands in New York. In the last 10 years, Kestrel has protected more than 2,000 acres in the heart of this region, which The Nature Conservancy argues contains the highest concentrations of complex and varied habitats in Southern New England. Kestrel also leads a partnership of all the land trusts in this region to proactively conserve another 10,000 acres in the next two years.

BioMap of the Hadley, MA, area. Each color shows a specific type of Core Habit or Critical Natural Landscape: the more colors, the more important the area is for biodiversity, as shown along the Mt. Holyoke Range at the bottom of the map. Image Credit: MassWildlife/BioMap.

The Quabbin to Cardigan Partnership focuses on the two million acres in the Monadnock Highlands of north-central Massachusetts and western New Hampshire, including the Quabbin Reservoir. In the last ten years, Kestrel has protected over 12,000 acres in this area, which includes the towns of Pelham, Shutesbury, Sunderland, Leverett, and Belchertown, Massachusetts.

One example of a recent landscape-scale conservation that was informed by BioMap data was an effort that Kestrel’s team dubbed the “Mountain Waters Project.” This initiative is permanently protecting more than 700 acres of wild and working lands in and adjacent to Southampton, Massachusetts. The project is named for Pomeroy Mountain and the waters that flow through its surrounding forests, feeding the Mahan and Connecticut rivers and providing clean drinking water for the Tighe-Carmody Reservoir and Barnes Aquifer in the more densely populated Holyoke area to the south. Two-thirds of the parcels conserved through this effort provide Core Habitat and nearly all are designated as Critical Natural Landscape. They generally have high climate resilience and provide valuable landscape connectivity and many intact forest blocks.

Farmland, Too, Can Boost Biodiversity

While we often think of forests and wetlands as the places that provide habitat for wildlife, considerable biodiversity can also be supported by the abundant farmlands. Along the Connecticut River in Massachusetts, rich soils have made farmland the dominant habitat type, often including smaller areas of floodplain forests and wetlands adjacent to farms. In the hill towns to the north, forests are the dominant land type, with patches of farmland interspersed within that ecosystem.

Farmland protection efforts focus on conserving active farmland for growing food and other agricultural products, which is a critical way of ensuring food security in our region and supporting our local rural economies. But for many species, the value of farmland lies in the “edge habitat” it creates, where two or more habitat types abut one another. The combination of habitats in close proximity to farmland may create just the right conditions for certain species, such as white-tailed deer or the threatened eastern spadefoot, an amphibian similar to a toad. The American kestrel, a small falcon for which Kestrel Land Trust was named, uses a variety of farmland habitats to hunt for invertebrates and small mammals.

Other species require large areas of open land that can be found on farms. Grassland birds, many of which are in significant decline, are regularly found in these wide-open farm fields. Vesper sparrows, listed as threatened in Massachusetts, often nest in farmland. Local potato fields are one of their most preferred habitats. Bobolinks, a boldly patterned bird, breed in local meadows and hayfields. The less visible Savannah sparrow prefers similar habitat. Managing hayfields to allow these species to nest successfully can be challenging for farmers, but for those who are willing to try, incentive programs are available that encourage cutting hay at times of the year that will increase the grassland birds’ nesting success.

Local farmland often supports a variety of bird species like snow buntings that breed in the northern tundra during summer but migrate south and forage for food on farms. Even the majestic snowy owl can sometimes be spotted hunting in local fields. The presence of man-made structures like old barns can make farms desirable for some bat and bird species. These aerial insectivores—animals that fly and catch insects for food—need a structure to roost in or to build their nests. Barn swallows are local, common aerial insectivores that are part of a group of birds in great decline in North America.

Local farmland also makes a big contribution to more abundant migratory and resident birds. Red-winged blackbirds and dark-eyed juncos, though common, are not immune to the challenges causing the biodiversity crisis, and they benefit from the habitat provided by our region’s farms. So do flocks of American robins, American crows, and Canada geese that forage in farmland, which helps keep these familiar species common in our landscape.

While there are often many benefits to conserving a parcel of land, including growing food, creating space for public recreation, protecting water quality, or sequestering carbon, saving wildlife habitat is often at the top of the list. By protecting wildlands, woodlands, wetlands, and farmland in our region, we can help the common and the not-so-common species survive in the Connecticut River valley—and stem the advance of biodiversity loss in our region.

Kari Blood is the Community Engagement Director with Kestrel Land Trust and has worked in the land conservation arena for fifteen years. Kestrel Land Trust is our newest River Partner. See their ad and news in “Let’s Go” in each issue.