This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

Image Credits: Mary Holland and Carolyn Vallas

The Cormorant Controversy

Anglers who fish Chatfield Hollow State Park in Killingworth, Connecticut, swear that cormorants have figured out when trout stocking is due. They may be on to something. It seems that hardly have the trout hit the water at this heavily stocked park than the glossy black birds are diving and gulping them down like foodies at a gourmet buffet. Even worse for anglers who troop there to cash in on its liberal supply of fish, once those birds—specifically the species commonly dubbed the “double-crested cormorant”—show up, even the trout that survive stop biting.

The much-maligned bird is a remarkable creature, exquisitely adapted to life over, on, and under the water. It flies 35 miles per hour, can cover a yard underwater in a couple of seconds, and can dive more than 100 feet. Its streamlined form, smoothed by feathers low in preen oil so they compress and reduce drag under water, is propelled by powerful simultaneous backwards thrusts of webbed feet and steered by its wings.

Cormorant with a flounder near the mouth of the Connecticut River in Old Lyme, CT. Image Credit: Getty Images/Wirestock

Biology and behavior make cormorants fish-eating machines. “They catch fish better than some fish,” says Milan Bull, Senior Director of Science and Conservation at the Connecticut Audubon Society. “They are amazing under water.” Its neck shoots out like a striking rattlesnake to snag prey in its hook-tipped bill. Smaller fish are scooped up by the bird’s stretchy mouth and swallowed immediately. Cormorants surface and manipulate larger fish for swallowing head down.

It’s no surprise that many of the fishermen with empty creels want Connecticut authorities to reduce cormorant numbers by lethally culling them. Several state and federal agencies, some in New England, cull double-crested cormorants, not just because they eat lots of fish—a pound a day per bird—but because their messy breeding colonies and roosts destroy nesting sites of other aquatic and wading birds.

As for culling in Connecticut, it’s not happening. “Connecticut’s cormorant population has been stable over the past two decades,” says Min T. Huang, who leads the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection’s migratory bird program. There is no need to reduce numbers, he says.

If this is not good news for fishermen, it is for bird lovers, some of whom go bonkers over killing cormorants. Animal rights groups decry it as “slaughter,” and even mainstream environmental groups have opposed it, opting for frightening them away with noise, deterring them with netting, and other nonlethal means of controlling the population called hazing.

Grid system and shelters to keep cormorants away and protect common tern chicks, Popasquash Island, Lake Champlain, VT. Image Credit: Audubon Vermont

The cormorant controversy has a wide reach, as does the bird itself. About a million double-crested cormorants winter, breed (in spring and summer), or migrate in or through every state in the Union and southern Canada and south into Mexico. At one time or another in the year, double-crested cormorants can be found along Atlantic coasts from the Canadian Maritimes to Mexico’s Yucatan and on the Pacific from southern Alaska to just south of Baja California. Most leave New England and winter in the Southeast.

Cormorant nesting colonies in our area are mostly, but not completely, coastal. In Massachusetts, about 11,000 breeding pairs nest in colonies sprinkled along the coast and islands, according to Andrew Vitz, Massachusetts’s state ornithologist. Along the Connecticut coast, cormorants favor islands, such as Gates Island off Mystic. New Hampshire’s sole breeding colony is on Lunging Island at the Isles of Shoals, six miles from the mainland. Neither Massachusetts nor New Hampshire use lethal means to cull cormorants.

Although land-bound, Vermont has cormorants galore on Lake Champlain where an estimated 8,000 of them live. One colony of about 500 nesting pairs lies on the Vermont side of Lake Champlain, while the Four Brothers, rocky islets over the New York border southwest of Burlington, is another stronghold. There is a new colony on Lake Memphremagog on a private island in the Quebec side of the lake, but no known breeding colonies in the Connecticut River watershed, says John Gobeille, wildlife biologist with the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department.

Given that foraging flights can cover about forty miles, cormorants can range far inland from the coast and from Lake Champlain, especially immature birds and nonbreeding adults. “You are likely to see them any place that has fish,” says Vitz. They can show up in season throughout most of the watershed states, regularly frequenting the area around the Vernon Dam between Vernon, Vermont, and Hinsdale, New Hampshire, increasing in numbers the closer the river is to the sea. These are mostly foraging flocks and can more often be seen during the spring and fall migration periods. Bull of Connecticut Audubon says he knows when river herring are running upstream to spawn when cormorants gather on the Connecticut River and other spawning streams.

Double-crested cormorants were not always so numerous. Since colonial times their numbers have cycled through extreme ups and downs. John James Audubon reported seeing millions of cormorants in one day in December 1820, but even by then they were killed because they took too many fish, for their feathers, and as food. It may be hard to believe, but some cultures—Iceland for example—consider cormorant good eating, although it has been described as like chewing on a tire.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, though, cormorants were rare enough that the sighting of one near Holyoke, Massachusetts, in 1925 merited a note in the prestigious ornithology journal, The Auk. The observer, who first thought he’d spied a loon, wrote, “Cormorants use the Connecticut Valley but casually,” noting the last had been seen in the 1880s.

Numbers eventually rebounded, only to be knocked back again by their ferocious consumption of fish laden with DDT and other pesticides. Perhaps only 32,000 nesting pairs remained by the start of the 1970s. After the banning of DDT and increased protection for cormorants, their populations began to rebuild. Bull first documented their return to Connecticut with a sighting off Norwalk in 1979. One pair nested on Lake Champlain in 1981, followed by flocks the next year. Within a few years, they were reproducing explosively over much of their range.

Audubon Vermont has been working to protect terns nesting on Popasquash Island in Lake Champlain from predation by cormorants. Image Credit: Audubon Vermont

What was hailed as a conservation success story, however, has, for some state fish and wildlife agencies, become too much of a good thing. The astonishing population surge of this North American bird has caught many fish and wildlife biologists in a thankless crunch between birding groups and wildlife management protocols.

Killing cormorants, which is achieved either by shooting them or destroying their eggs, is anathema to animal rights groups like the Friends of Animals. “We expect the federal government to protect native wildlife, not intentionally cause major declines,” stated Michael Harris, the organization’s legal director, in opposition to cormorant culling in the Pacific Northwest’s Columbia River Basin. The Animal Legal Defense Fund has called cormorants destined for control a “scapegoat” for poor environmental policies.

The process is not popular with mainstream conservation organizations, either. BirdLife International, a consortium of birding organizations, claims that lethal cormorant control is scientifically unwarranted and that “Seabirds are going to…eat fish.” The National Audubon Society has opposed the use of large-scale lethal control of cormorants but left it open for “judicious use of lethal control of birds when necessary” and “when backed by solid scientific evidence.” Mostly, though, conservation groups urge nonlethal means, such as removing nests and scare tactics.

Audubon Vermont, an arm of the National Audubon Society, has used nonlethal means to keep double-crested cormorants off Lake Champlain’s rocky islets where they like to roost. Their activity there threatens the nesting of the common tern, which, despite its name and abundance elsewhere, is endangered in Vermont. These islets, which are as small as the “footprint of a house,” says Mark LaBar, Audubon Vermont’s conservation program manager, are critical to tern survival. Keeping cormorants out was simple, he says. Thin wire, set a yard above the ground, discouraged cormorants from landing, due to their low glide path. Since 1988, the tern population there has increased 300 percent, largely due to restoration efforts.

While good for the terns, sometimes hazing cormorants causes them to set up house elsewhere and restart the problem. “Our experience with nonlethal [methods] is that it has no effect on the birds. They just acclimate to it,” says Gobeille, of the state control program on Lake Champlain. The Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife has spent big dollars over the years to cut cormorant numbers by lethal control on Lake Champlain. Cormorants started nesting on state-managed Young Island there in 1982 and their numbers grew from a handful to thousands. By 1996 their pungent guano, reeking of ammonia and so acidic it changes soil chemistry, had killed virtually all of the trees on the island. “We rely primarily on lethal control,” says Gobeille, “although we are required to use nonlethal also, according to our federal permit.”

Because cormorants have federal protection under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, a state wildlife agency or private interest suffering cormorant damage cannot launch a lethal control effort without a permit from the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). With federal approval, states, tribes, individuals, and other entities are allowed “to lethally take cormorants to alleviate damage and conflicts associated with aquaculture and fishery resources, recreational and sport fisheries, property, natural resources, and threats to human health and safety.” Culling, however, is allowed only when nonlethal methods do not work.

The federal approval process is outlined in a rule, published by the USFWS in 2020, after a lengthy court battle in which environmental and animal rights organizations fought against lethal control. Gaining approval is not easy. “The permitting process is very slow, often taking a full year for a response after submitting a permit application,” says Gobeille.

Cormorant predation on fish is a source of contention between some environmental groups and fish and wildlife managers. The birds are known to eat more than 250 different kinds of fish, exactly which are dependent on location and season. The list includes many of commercial importance, not just sport fish, but others, such as menhaden, which are used for feed, oil, and bait. Most fishermen who spend time on or at the edge of water have seen cormorants take sport fish, from freshwater trout to saltwater flounder.

Bull wonders out loud whether cormorants are implicated in the demise of the winter flounder fishery, blamed to a large degree on rising temperatures and overfishing. While there is no science linking the two, says Bull, the rise of the cormorant population coincides with the fall of the winter flounder. With winter flounder about gone, it is now common to see cormorants with young summer founder in their bills.

It is documented that Columbia Basin cormorants in the Pacific Northwest eat 20 million salmon and steelhead smolts a year. That may seem immense but not when the fact that more than two million adult salmon spawn there and females can produce up to 17,000 eggs each. The normal survival rate from egg to adult is infinitesimal, about one percent.

It was mass killing of Columbia River cormorants by the US Army Corps of Engineers from 2015 to 2017 that triggered outcry from birding and animal rights groups resulting in modifications in federal exceptions for killing cormorants. It’s why the 2020 rule stipulates that nonlethal means must be tried first.

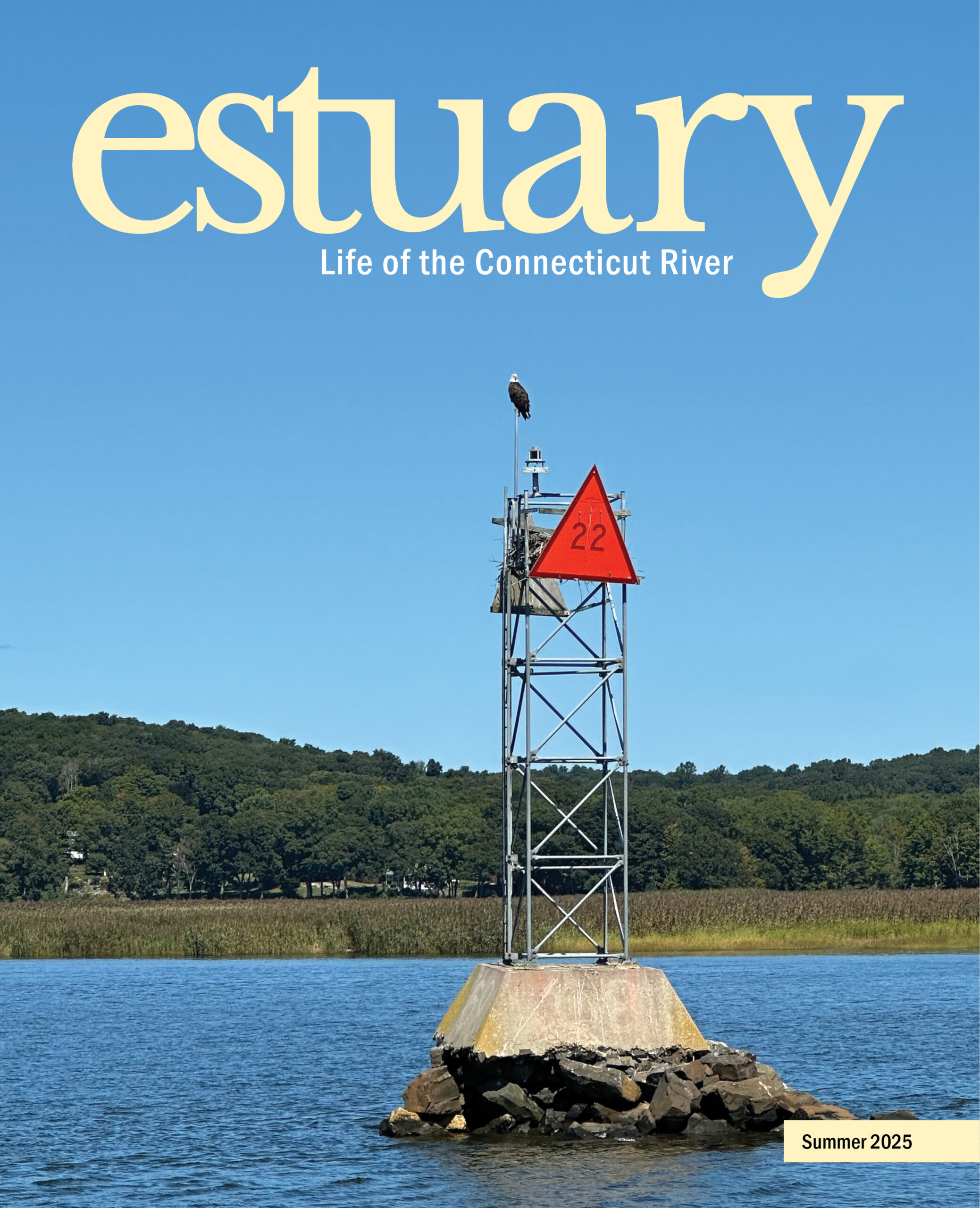

Left: Cormorant. Right: A common tern on a buoy off Popasquash Island, Lake Champlain, VT.

Image Credit: Trevor LaBarge

Understandably, the history of differing attitudes on cormorant control is, in the words of the US Department of Agriculture Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), “long and convoluted.” An APHIS report notes that in the late 1990s, “Agencies in ten states, ranging from the Southwest to the Northeast, considered cormorant predation to be of moderate to major concern to fishery management.” Then the agency added a caveat. “Overall, double-crested cormorants are not major consumers of commercial and sportfish species.”

At the same time, however, the report noted that at spots such as fish farms and stocking sites—Chatfield Hollow comes to mind—cormorants have severely depleted fish. Fish farms are particularly vulnerable because fish there are as easy to catch as shooting them in the proverbial barrel. You might as well put up a sign that says, “Eat at Joe’s,” quips Audubon Vermont’s LaBar.

A study by scientists from APHIS and Mississippi State University, published in 2023, showed that the presence of catfish aquaculture was “a significant driver of distribution and abundance” of cormorants. Their conclusion, briefly, bolsters Milan Bull’s observations about cormorants and river herring: Where there are fish, there are cormorants. The question is, can we live with that?

Ed Riccuiti is a freelance writer and published author who writes about history, nature, science, conservation, and law enforcement.