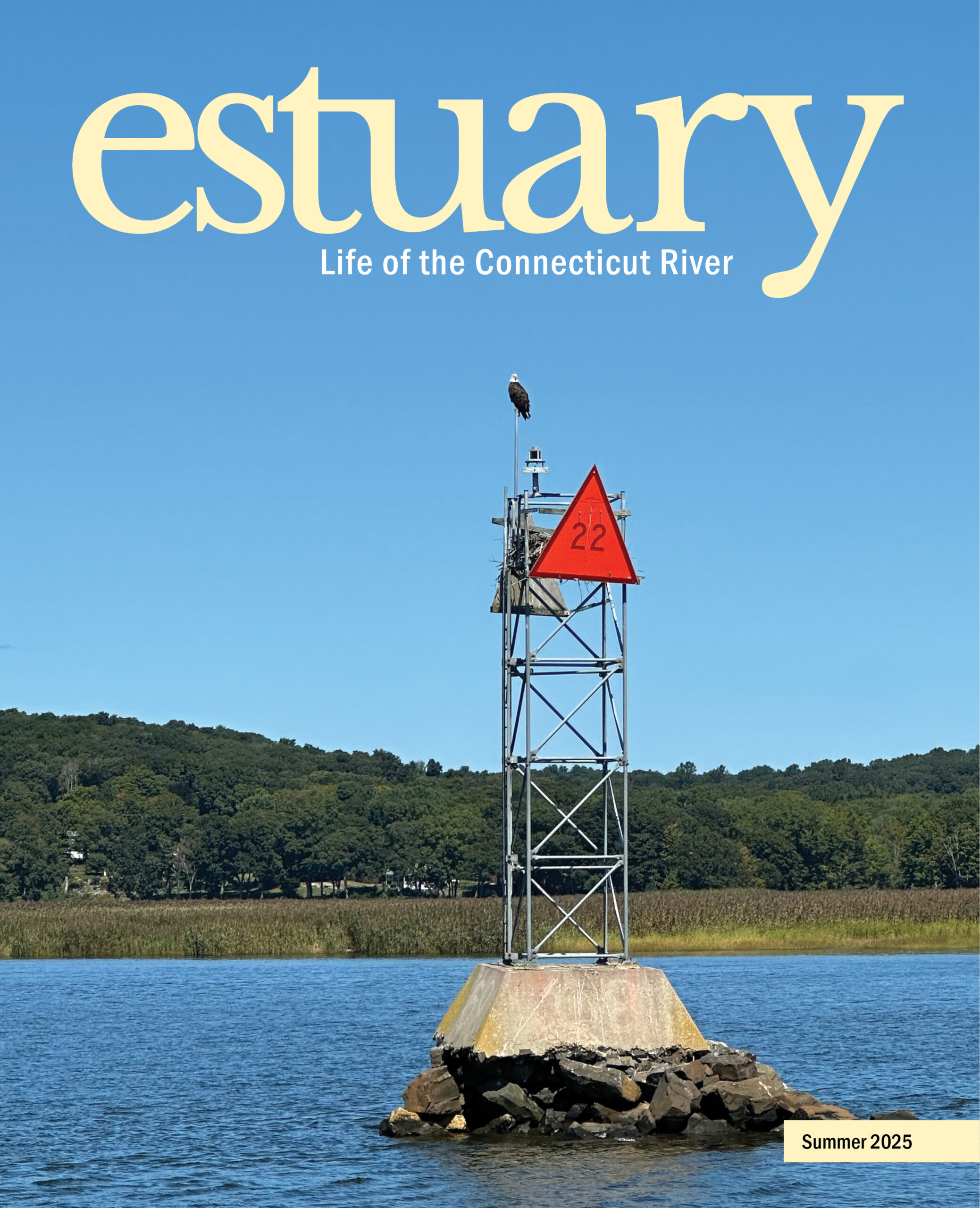

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

It seemed like such a good idea. Just coat seeds with insecticide so that the plants sprout with the insecticide systemically already in their leaves, ready to repel and kill the pests. The theory was that it would save on the amount of chemicals sprayed by airplanes and towed sprayers; it would be environmentally sound because of the much lower volume of chemicals needed. And, crop yields should increase.

Neonicotinoids (neonics, for short) entered the lawn and golf course markets in the early 1990s and today represent the largest use of insecticides in North America.

But neonics have proven to be harmful, even fatal, to birds, bees, and other helpful insects that pollinate the very plants being “protected.” What’s more, only 2 to 5 percent of the toxic substance remains in the plant; 90 percent washes out of the plant into fields and leaches into streams and rivers, thus harming important aquatic and human life. On top of that, it has now been well-documented by scientists that the yield of the crops responsible for the greatest use by far of neonics, corn and soybeans, has not increased because of the use of the pesticide.

Here is yet another ostensibly “good” deed gone terribly awry in certain respects, which provides another partial explanation as to why the bird population in North America has dropped from 9 billion in 1970 to 6 billion today.

Here is yet another ostensibly “good” deed gone terribly awry in certain respects, which provides another partial explanation as to why the bird population in North America has dropped from 9 billion in 1970 to 6 billion today.

Louise Washer of Norwalk, Connecticut, president of the Norwalk River Watershed Association and a member of the Pollinator Pathway board, refers to neonics as “the new DDT.” She notes that neonics are orders of magnitude more toxic than DDT. In her view, “agriculture has become the thing that kills the insects we rely on to have the food.” Washer advocates against “high harm, low benefit” uses such as on lawns and golf courses. She represents one of several groups supporting a pending law in Connecticut to ban certain insecticide brands from such use.

Professor John Tooker in the Department of Entomology at the University of Pennsylvania concurs with the conclusion that “use of neonic seed coatings in large-acreage crops is unnecessary and is providing few if any economic benefits to those crops (corn and soybeans, etc.). But neonics have value […] in fruit and vegetable production.” He adds, “As with most subjects, the details matter,” and recommends that responsible policies need the engagement of the state’s own agricultural experts.

Because the matter is not clear-cut, responsible legislation is difficult and takes time. Lobbyists for the insecticide manufacturers are unlikely to be helpful. It’s a matter for objective experts. In June 2024 Vermont became the second state (after New York) to ban the major uses of neonics. It bans the use of neonics for ornamental plants starting in 2025 and for agricultural use in 2029.

The neonics matter is yet another example for which it would make sense to have consistent rules throughout the Connecticut River watershed; hopefully, Connecticut—where scientists at the University of Connecticut have found neonics in streams and rivers throughout the state—New Hampshire, and Massachusetts will not be far behind Vermont.

Who does one turn to for advocacy on the legislative front? How about the Boston-based Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) whose mission is “to protect New England’s environment for the benefit of all people. We use the law, science, and the market to create solutions that preserve our natural resources, build healthy communities, and sustain a vibrant economy.”

According to CLF’s Scott Sanderson, “CLF is pushing forward bills in Connecticut and Massachusetts to fight the overuse of these toxic pesticides. Both bills ban the use of neonics on corn, soy, and wheat, since studies have established that the pesticides don’t benefit farmers. The bills wouldn’t impact neonic use on other crops where the pesticides have shown to offer farmers some economic benefits. Connecticut’s bill will also ban neonics for non-agricultural purposes. There’s no excuse for sports fields or ornamental landscaping to introduce toxic chemicals into our environment. Golf courses can find ways to keep their greens lush and manicured without poisoning butterflies, bees, and songbirds.”

Cropdusters still spray crops in the Connecticut River watershed by helicopter and airplane using tried and true insecticides from the past. It’s a risky business for the 3,400 registered Ag pilots in the US and the more than 100 million acres they treat each year, but some of the insecticides at their disposal may be safer for our bees, butterflies, and other pollinators and birds than the seed-coated neonics. Suppliers of seeds should of course provide farmers with the better and safer options.

Dick Shriver

Publisher & Editor