This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

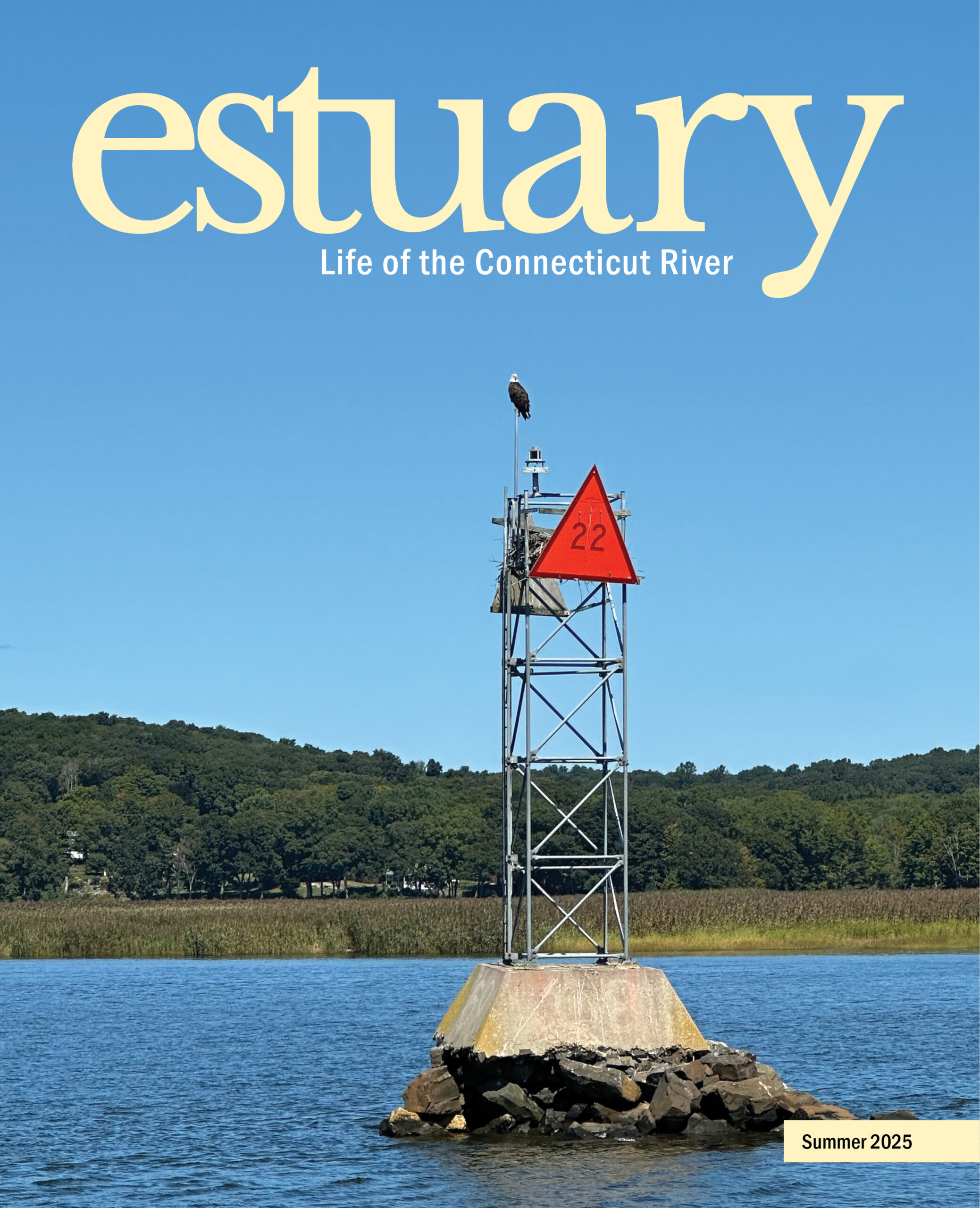

Mountain laurel in the wild, lower Connecticut River valley.

Some folks go on an annual religious pilgrimage. My annual journey is to see mountain laurel which blooms from late May to early June. One year, I sprained my ankle, and a friend drove me through Nehantic State Forest in Lyme, Connecticut. A spectacular drift of laurel was easily seen driving down Bear Hill Road in Middletown where it grew under the power lines—until Eversource removed it to access their rights-of-way.

Another year I wasn’t sure I was going to make it in time, but the long, cool spring created one of the most wonderful blooms in many years. I’d heard about the Nature Conservancy’s Selden Creek Preserve in Lyme on Joshuatown Road. I’d visited the Ravine Preserve across the road, but not this one.

As you enter the loop trail, the laurel envelopes you. That year, the blooms were snowy white on branches feet above our heads. At one spot, the laurel enveloped us in a 360-degree panorama. As we continued, it arched over the trail creating a canopy suitable for a wedding, but just for us, alone in the woods. It was beautiful and humbling at the same time that Mother Nature would share such magnificence with us humans.

Henry Hudson first described mountain laurel in his 1609 log of a trip to Cape Cod. In 1624, Captain John Smith noted its presence in his The Generall Historie of Virginia. John Bartram, the famous botanist from Philadelphia, sent the first plant sample to England in 1734, and naturalist Mark Catesby published the first color print of the plant in 1743. But it was Swedish botanist Peter Kalm, who sent specimens of laurel to the taxonomist Carl Linnaeus, who prevailed in the naming of the plant. In 1753 Linnaeus called the plant’s genus Kalmia for his former student and latifolia for its characteristic wide leaf.

In May and June 1791, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison took a vacation through the Northeast to get away from the hustle and bustle of government in Philadelphia. They traveled down the Connecticut River from Northampton, Massachusetts, stopping in Hartford and Middletown, Connecticut. On the way through the southern reach of the river, Jefferson remarked that he saw the most beautiful shrub ever—our mountain laurel.

Mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) was designated Connecticut’s state flower in 1907, and well it should be since it is so widespread, enormous, and gorgeous. Mountain laurel, in fact, is found from Canada to Florida. Although it can grow from five to fifteen feet or more in height in the wild, cultivars can be purchased of dwarf varieties a mere fifteen inches high when mature. Amazing variations of laurel are available at nurseries, many developed by Connecticut plant breeder Richard Jaynes who worked for many years at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES) in New Haven. He literally wrote the book on laurel: Kalmia: Mountain Laurel and Related Species (1997).

While laurel grows in shade, here it likes edges of forest, especially craggy roadsides and the steep bedrock-exposed slopes of the Connecticut River. We are so fortunate that the river takes that sharp curve south of Middletown where the laurel grows from the riverbank to the top of the highest outcrops.

The flowers are cup-shaped and can range from white to pink to deep rose in the same area of the forest. Inside the rim are tiny dots, hence its nickname “calico-bush.” The flowers have a unique way of dispensing pollen. The stamens are arched, with the tips tucked under the rim. When a pollinator lands on the flower, the weight of the insect releases the stamen, which hurls the pollen like a catapult. Laurel sets buds in the fall for the next year’s bloom.

A mountain laurel cultivar.

Laurel is a broad-leafed evergreen in the Ericaceae (heath) family that includes rhododendrons, azaleas, blueberries, and cranberries, but unlike its cousins all parts of the plant are poisonous, containing a toxin called andromedotoxin which disrupts sodium ion channels in the brain. Ingesting it can cause nausea, pain, and other unpleasant symptoms. It was called “lambkill” by early settlers when they noticed its effect on livestock. Honey made from bees nectaring on laurel is also toxic. Its toxicity was unknown to Native people who made spoons from laurel and called it “spoonwood.” Well-liked by carvers, mountain laurel was once used for pipe bowls. Because of our current knowledge of its lethal nature, it should not be used in any form, including as kindling. Unfortunately, that doesn’t seem to deter deer from consuming it, at least in my yard.

New research on the relationship between laurel and the mycorrhizal fungal network in the soil where it grows shows an important role in the biogeochemical function with regard to carbon and nitrogen. The Yale Forest Forum explains that the fungal partner provides the plant with greater access to nitrogen and other nutrients in the soil, while the plant provides the fungus with carbon from photosynthesis. This symbiotic relationship may account for the abundance of mountain laurel in Connecticut forests. Such a shrubby laurel understory, though, can be a trekker’s nightmare. Often referred to as “laurel hell,” the thicket of numerous thin branches is nearly impossible to traverse.

As the snow melts and the maples redden with buds, I look forward to the pursuit again this year, to marvel at one of the Connecticut River valley’s great natural treasures.

Alison C. Guinness is a resident of East Haddam where she researches the local earthquake phenomenon called the Moodus Noises. She curated an exhibit at the Connecticut River Museum on brownstone and searches for important uses of sandstone around the world.