This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

How did a man who left high school at the age of fifteen have a major impact on the development of some of our nation’s premier institutions of higher education, including the flagship universities of Vermont, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts? That would be a person with a core understanding of self and an uncompromising work ethic. That man was Justin Smith Morrill.

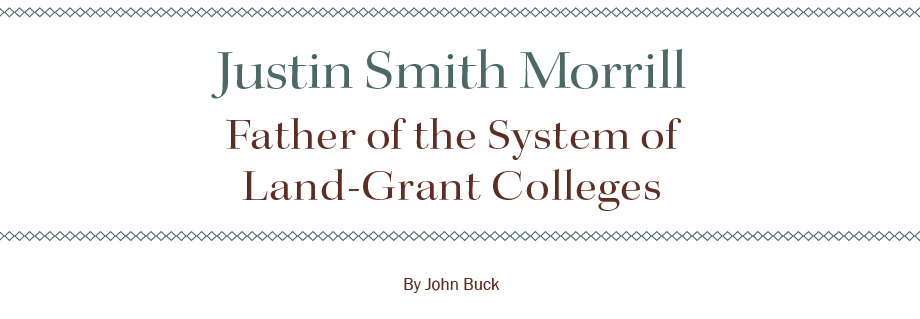

Justin Smith Morrill. Image Credit: Library of Congress (Justin Smith Morrill).

Morrill was born on his parents’ farm in Strafford, Vermont, on April 14, 1810 (less than twenty years after Vermont’s admission to the Union). He was raised by parents of modest means and was unable to pursue an education past the age of fifteen. Still, he was a very bright and ambitious young man. He developed an acumen for business by starting as a merchant’s clerk in Strafford and then as proprietor of his own business. He expanded his knowledge and skill through a business partnership with well-known Vermont judge Jedidiah Harris. He and Harris owned four profitable stores throughout Vermont. Success allowed Morrill to capitalize on a growing nation by investing in banks, railroads, and real estate. His initiative served him very well—so much so that he was able to retire from business before his 40th birthday and return to Strafford to enjoy life as a gentleman farmer.

In addition to his Strafford farm, Morrill held the offices of Town Auditor and Justice of the Peace. His growing interest in politics led him to become involved in local Whig Party politics where he soon rose to Orange County party chair. The Whig Party had become a nationally active political party during the early and mid-nineteenth century. It was responsible for electing to the presidency William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Millard Filmore.

Whigs were comprised largely of business entrepreneurs, professionals, and, importantly, the middle class. They disdained presidential power for fear of executive tyranny over congressional authority, supported tariffs, and a national banking system. A schism between northern Whigs and their southern counterparts, however, developed over the issue of slavery, and the party all but dissolved shortly after its 1854 presidential convention. But before the official end of the Whig party, Morrill was elected to the House of Representatives that November representing Vermont.

Morrill was among the northern Whig remnants who were part of the founding members of the Republican Party that got Abraham Lincoln elected in 1860. He won reelection to the House four more times before winning one of Vermont’s US Senate seats in 1866. While in the House, Morrill authored two significant bills. The first, the Morrill Tariff Act of 1861, was enacted to offset deficits incurred by the Buchanan administration. It was controversial with southern Democrats who saw it as economically obstructive to their slave-based economy. Viewing the tariffs as a form of punishment by abolitionist legislators, the act further incited successionist sentiments.

Morrill, however, is best remembered for his efforts to provide federally supported education to the common people and to ensure that emancipated slaves would have access to the same educational opportunities as others. Morrill’s second major legislative accomplishment was the Land-Grant College Act of 1862. Perhaps rooted in the intentions stated by the Continental Congress that, “Knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools, and the means of education shall forever be encouraged,” Morrill felt strongly that a democracy could not be successful and the young country could not be globally competitive without an educated citizenry. Perhaps because of his minimal formal education and his Whig roots, he felt it was the responsibility of the federal government to help states educate their citizens, particularly in the fields of agricultural, mechanical arts (engineering), and military studies (known today as the ROTC).

The sea-change significance of this legislation is that a post-secondary education would no longer be the domain of the privileged, but would open the door to opportunities for middle- and working-class people. Significantly influenced by agricultural science proponent and Illinois College professor Jonathan Baldwin Turner, Morrill drafted the act that began:

AN ACT Donating Public Lands to the several States and Territories which may provide Colleges for the Benefit of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That there be granted to the several States, for the purposes hereinafter mentioned, an amount of public land, to be apportioned to each State a quantity equal to thirty thousand acres for each senator and representative in Congress to which the States are respectively entitled by the apportionment under the census of eighteen hundred and sixty: Provided, That no mineral lands shall be selected or purchased under the provisions of this Act.

The sale of these Federal acres laid the foundation for a national system of state colleges and universities. In some cases, the land sales financed existing institutions such as the University of Vermont. In other cases, new schools were chartered by the states. Major universities such as Nebraska, Washington State, Clemson, and Cornell were chartered as land-grant schools. Fifty-seven schools were ultimately designated land-grant schools.

Morrill Hall, University of Vermont. Image Credits: Wikimedia Commons (plaque). Niranjan Arminius, Wikimedia Commons (Hall).

While one can appreciate the impact of this act today, the Land-Grant Act, being a product of the social norms of its time, was not without its flaws. It is important to note that Federal lands used to finance the Act were lands largely acquired through treaties (not always upheld) and outright adverse possession from peoples of the First Nations. Untold numbers of Native Americans were displaced or denied use of ancestral lands as a result. Furthermore, higher education was limited to White men. Finally, perhaps because only men of at least twenty-one years of age could vote and hold federal office, only men were identified in the act’s language. Although the Whigs and subsequent Republicans fought for the abolition of slavery, the nineteenth century was still very racially and gender segregated.

Not to be deterred, Morrill introduced a second Land-Grant Act that was enacted in 1890 to address racial inequality. This second act, aimed at the reunified southern states, added nineteen schools. It required the former Confederate states to either provide access to land-grant universities regardless of race or to establish separate land-grant institutions for Black students. Because racist sentiments enforced by Jim Crow laws remained in the forefront in those states, Black students would not be allowed into the existing land-grant colleges. Instead, a core group of what are now commonly known as Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were founded. They include Alabama A&M, Prairie View A&M University, and Tuskegee University. Although many colleges and universities were admitting women in the nineteenth century, co-ed classes were not common until the latter half of the twentieth century. Native peoples would have to wait until the end of the century to be included.

Morrill carried his Whig to Republican ideology through his entire political career. He was a fiscal conservative who opposed large government surpluses and over-taxation; he opposed Congressional pay raises, actually giving back his raise to the Vermont treasury. He voted to convict President Andrew Johnson at his impeachment trial and was an early supporter of the 14th amendment (i.e., citizenship by birth or naturalization and prohibition of holding office after participating in an insurrection). Being the good public servant that he was, he never lost sight of his Vermont constituency. Like other historic figures (e.g., Thomas Jefferson), however, Morrill was a man of his social and cultural times. He opposed women’s suffrage, for example, and efforts to formalize the eight-hour work day.

Morrill died in 1898 at the age of 88 and is buried in the family plot in Strafford. At the time of his death, his nearly forty-five years in Congress ranked him as America’s longest-serving congressman. Now more than one hundred years after his passing, Morrill’s higher education legacy lives on. In addition to the original 1862 act and its 1890 companion, the Smith-Lever Act of 1914 included extension education as a function of land-grant funding. Most recently, in 1994, land-grant funding was further expanded to include support for thirty-five tribal colleges on Indian reservation lands.

The significance of the Land-Grant Acts has not been lost on those colleges and universities supported by its benevolence in the naming of a “Morrill Hall” on many of their campuses. Morrill’s Strafford homestead is a National Historic Landmark maintained by the Friends of the Morrill Homestead (MorrillHomestead.org.) and is open to the public from May to October.

John Buck lives in Waterbury Center, Vermont, with his wife, Cathy. He is a retired state wildlife biologist and a full-time maple syrup producer who, with his family, manages their 70-acre maple farm.