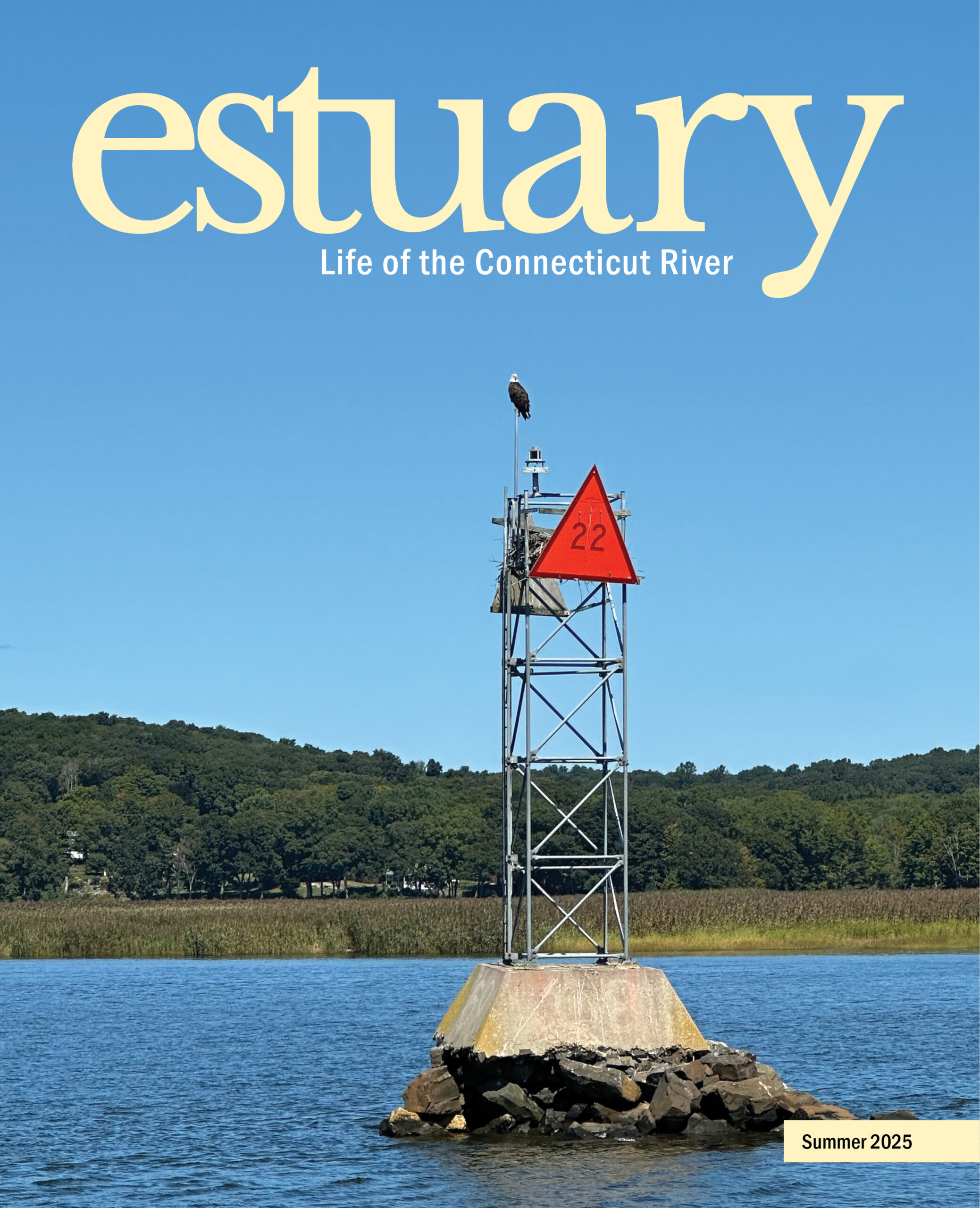

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

Summit Houses of the Pioneer Valley

by John Burk

Inspired by artists and writers such as Thomas Cole and Timothy Dwight, many tourists during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries came to the Connecticut River valley to visit the region’s mountain houses atop peaks such as Mount Tom, Mount Holyoke, and Mount Sugarloaf. Visitors enjoyed the panoramic views and amenities such as restaurants, observatories, theaters, concerts, and inclined railroads.

After decades of prosperity, by the late 1920s the popularity of summit houses began to decline. Increasing automobile ownership meant people had more options, and then the Great Depression hit. Even before that, several of the Connecticut Valley’s summit houses were lost to fire, a constant danger for wooden buildings on isolated ridges. Today, hikers can visit the sites of these mountain houses—and one that has survived 175 years—to enjoy the view and imagine what these places must have been like in their heyday.

Remains of the former Eyrie House hotel on Mount Nonotuck at the northern end of Mount Tom’s ridge with the Connecticut River in the background. Image Credit: John Burk Photography.

Mount Nonotuck

On Mount Nonotuck, an 820-foot peak at the northern end of Mount Tom’s ridge in Holyoke and Easthampton, I followed an interpretive trail to the former site of a hotel known as the Eyrie House. The path led past stone walls, rocky lookouts, picnic groves, and ruins of a pavilion that hosted concerts and parties.

Owned by proprietor William Street, a businessman from Holyoke, the Eyrie House opened in 1861. Competition with the nearby Prospect House on Mount Holyoke prompted several expansions of the establishment. By 1882 the hotel had thirty guest rooms and a variety of other attractions, such as elevated promenades, a croquet court, and even live animal exhibits.

In the 1890s Street began construction of a larger stone hotel and an inclined railway, but financial problems halted both projects. In April 1901 a fire, ignited by wind-swept embers after Street cremated two horses, destroyed the Eyrie House. Street, who was substantially underinsured, never rebuilt. The State of Massachusetts acquired the land several years later after establishment of Mount Tom State Reservation in 1902.

The easiest route to the Eyrie House interpretive trail is via a 1.2-mile walk on Mount Nonotuck Road (closed to vehicles), which begins at a gate near the Mount Tom Reservation visitor center. For a more rugged adventure, the New England National Scenic Trail (NET), which traverses Mount Tom’s ridge, crosses Mount Nonotuck Road near the hotel site. Parking is available at Mount Tom North Trailhead Park on East Street in Easthampton.

Mount Tom

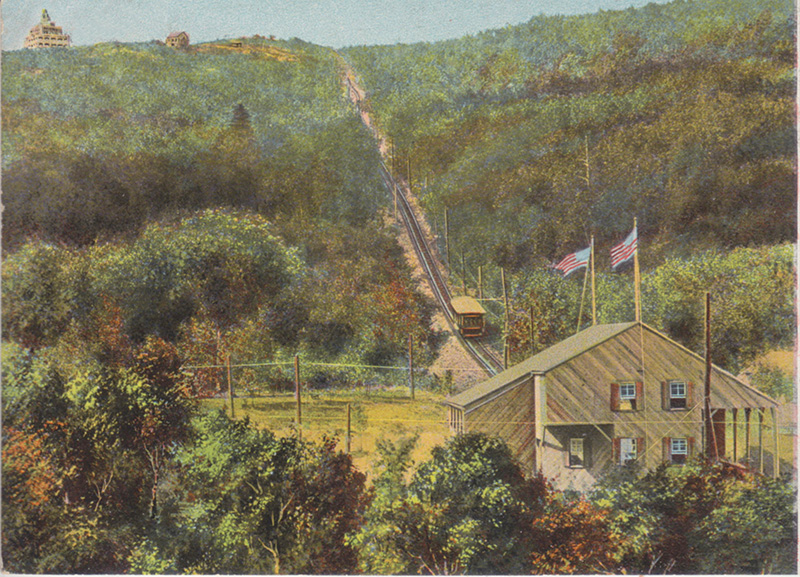

Three miles south on Mount Tom’s 1,201-foot summit, a large concrete foundation marks the former site of a mountain house that thrived during the early twentieth century. In 1897, to generate business from tourists and weekend visitors, the Holyoke Street Railway Company built the first of three summit buildings: a two-story pavilion with a restaurant, stage, and an observatory. An inclined railroad connected it to Mountain Park at the base of the east slopes. President William McKinley, who visited in 1898, reportedly described the view as “the most beautiful mountain outlook in the whole world.”

After a fire destroyed the pavilion in October 1900, an elaborate seven-story replacement, with a multi-level observatory and a large copper dome, opened the following year. With an average of 75,000 visitors annually, it remained a popular attraction through the 1920s.

In May 1929 this second summit house burned in an inferno that was visible from Hartford and other distant vantages. The third structure, a temporary steel building with a dining room, souvenir shop, and observation tower, was removed when the park closed in the late 1930s.

The most direct route to Mount Tom’s summit, a steep 0.8-mile ascent, is via the NET from the MA 141 trailhead near the Holyoke-Easthampton town line. The foundation (off-limits to the public), which houses antennas and transmitters for local radio and television stations and remnants of a boardwalk are visible at the former hotel site.

Mount Sugarloaf

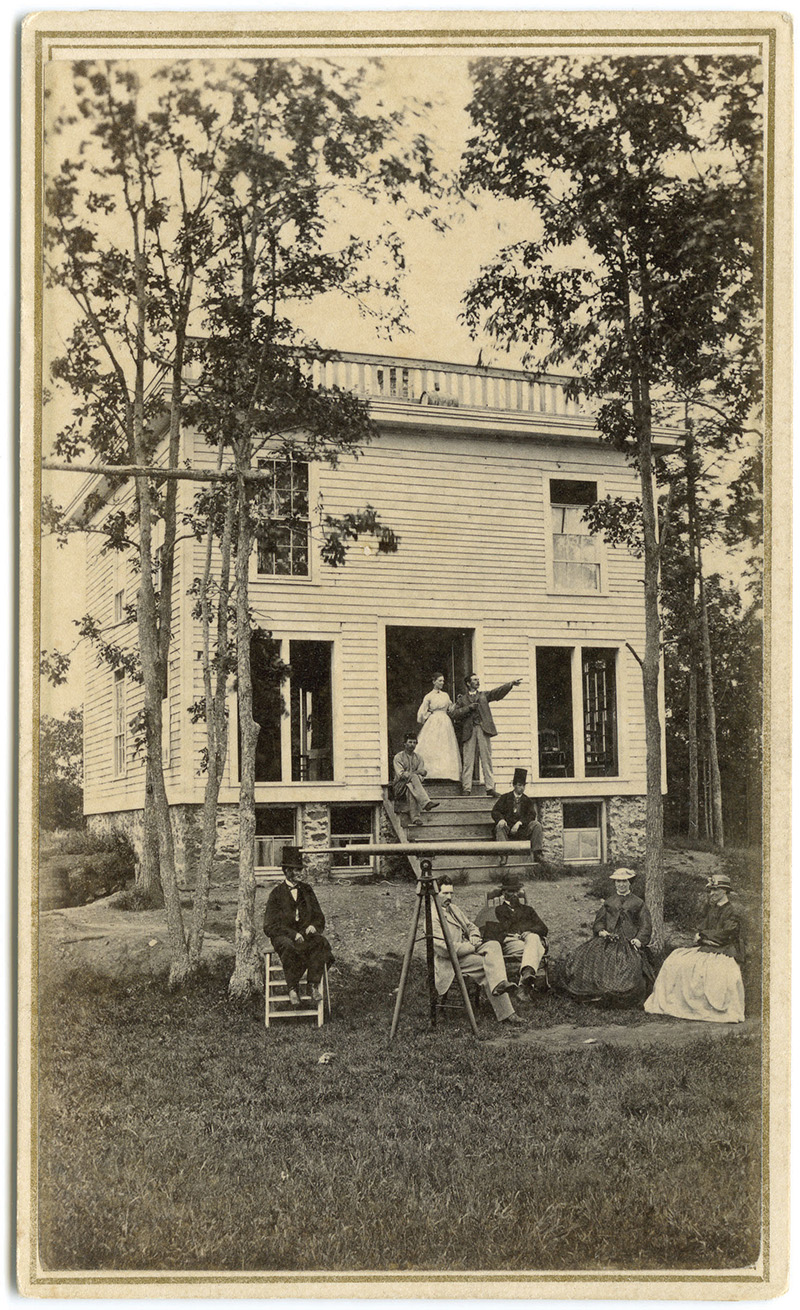

Tourists at Mount Sugarloaf’s Mountain House shortly after it opened, c.1865.

In the upper Pioneer Valley, Mount Sugarloaf’s Mountain House hotel in Deerfield was a popular destination in the late nineteenth century. Built in 1864, the three-story hotel featured twenty guest rooms and a porch with panoramic views. Declines in business caused the hotel to fall into disrepair during the early twentieth century, and it caught fire in March 1966. Firefighters were unable to reach it in time because the auto road was covered with snow. Today there’s no trace of the old hotel, but Mount Sugarloaf State Reservation’s present three-level pavilion can be reached via the auto road or the Pocumtuck Ridge Trail.

Mount Toby

Across the valley in Sunderland, developers briefly attempted to establish a resort on Mount Toby, the highest peak in the region. During the 1870s Rector Goss, a lumberman, built an enclosed six-story observation tower, horse stables, and carriage road from a railroad station at the base of the mountain. After Goss’ death, John Graves added a hotel at the summit in 1881. Shortly after its completion, a fire destroyed the hotel, tower, and stables. The road now serves as a popular hiking route to the summit, where a fire tower offers sweeping views across the region.

Mount Holyoke

A prominent attraction of the Pioneer Valley for 175 years, Mount Holyoke’s summit house stands as the lone survivor of the region’s mountain-house era. Development on Mount Holyoke, one of America’s first popular mountain destinations, began in the early 1820s when two buildings opened at the summit. In 1851 John W. French, a bookbinder from Northampton, built the Prospect House. A 600-foot-long inclined railroad linked the summit to the Halfway House on the middle slopes. During the 1860s French added rooms and opened a steamboat ferry to the Mount Tom railroad station on the west side of the river. A four-story addition, completed in 1894, increased the hotel’s capacity to forty guests.

The Holyoke Street Railway Company’s inclined railway from Mountain Park to the Summit House.

In the early twentieth century the Mount Holyoke Company and businessman Joseph Allen Skinner added electricity and plumbing, upgraded the railway, and built an auto road to the summit. The hotel permanently closed after the hurricane in September 1938 destroyed the 1894 addition. Skinner donated the property and surrounding land in 1940 to the state to establish Skinner State Park, which preserves the western portion of the Holyoke Range.

Mechanical problems ended the tram service in 1942. During the next four decades the Prospect House gradually deteriorated while officials and planners engaged in prolonged discussions about its future. After residents expressed strong support for preserving it in its original configuration, the Prospect House was restored in the 1980s as a visitor center.

A network of trails in the park, including Halfway House Trail, Tramway Trail, and a segment of the NET, provide a variety of options for hiking to the visitor center. The main trailheads are on MA 47 and Mountain Street in South Hadley. The auto road is open seasonally to vehicles from mid-May to October.

The Prospect House in its heyday, showing the 1894 addition destroyed by hurricane in 1938.

John Burk is a writer, photographer, and historian from western Massachusetts whose credits include books, guides, and articles in nature and regional publications.

Image Credits: Photograph Collection, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries (Mount Sugarloaf’s Mountain House).