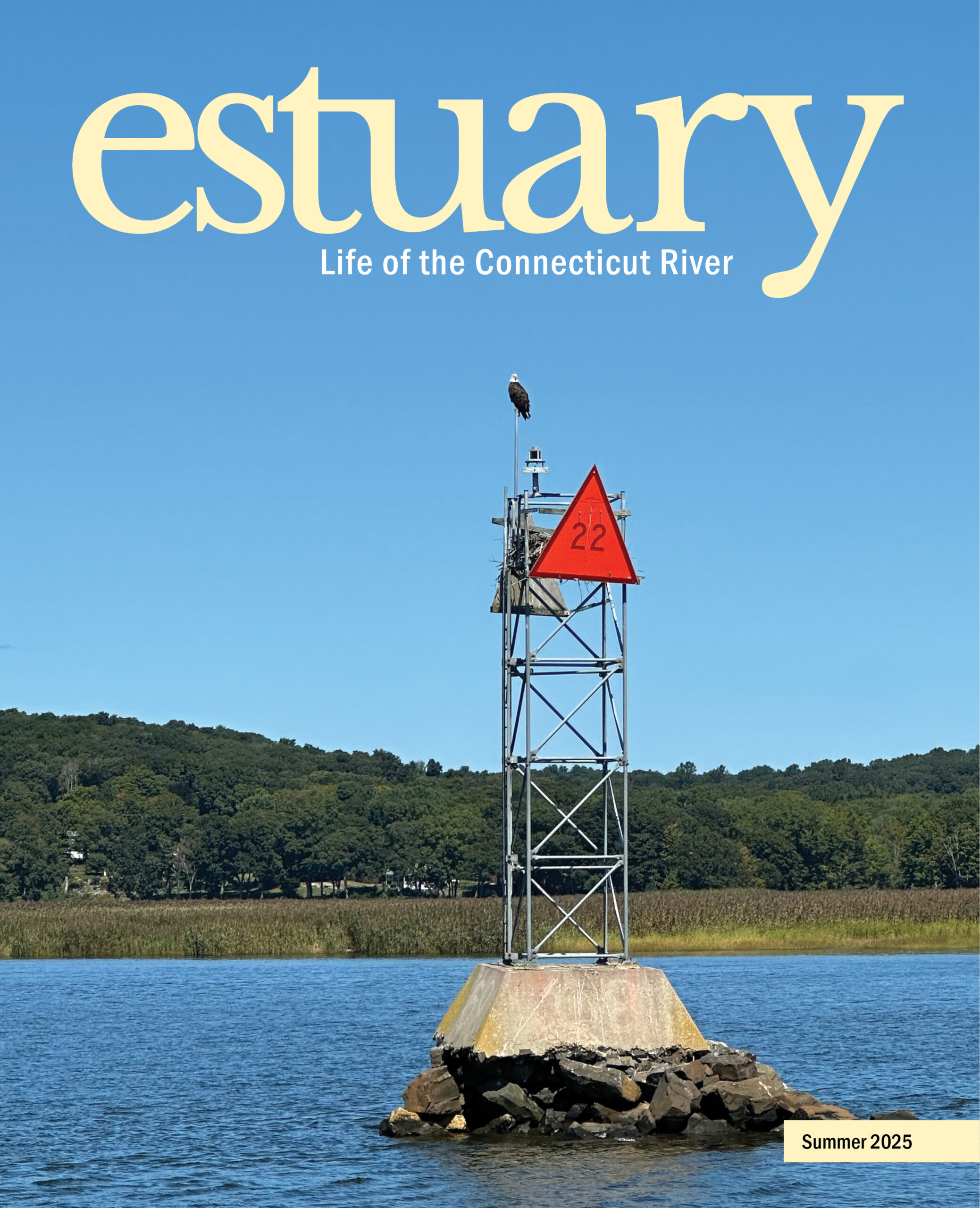

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue

An Ancient Fish, A Modern Mystery

by Steve Gephard and Sally Harold

Shortnose Sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum). Image Credit: Jeff Cherry, Wikimedia Commons.

Two species of sturgeon are found in the Connecticut River—the Atlantic and the shortnose. Both are anadromous, at least to a degree, and both are listed as endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA). Atlantic sturgeon (which in the past reached lengths of ten to twelve feet!) are rare upstream in the Connecticut River. Although they are commonly found in the mouth of our river, most are from the Hudson River and have come east to feed in coastal New England waters.

The spawning stock of Atlantic sturgeon in the Connecticut River may have diminished to less than ten individuals. In contrast, the shortnose sturgeon population is currently in the thousands! Shortnose reach only three to four feet in length. Both species were quite abundant at the time of European contact, but a commercial fishery that began in the 1600s, water pollution, and dam-building devastated populations in the Connecticut and all East Coast rivers.

Historically both species were found from the mouth of the river up to Turners Falls, Massachusetts. The bedrock falls there blocked the migration of the relatively weak-swimming sturgeon species even though salmon, shad, and river herring got past the falls.

James Gardner, a PhD candidate at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and Dr. Kate Buckman, an ecologist with the Connecticut River Conservancy (CRC), used eDNA to investigate the presence of sturgeon above the sturgeon’s previously documented range. Image Credit: Connecticut River Conservancy.

The Atlantic sturgeon is a classic anadromous species: it leaves freshwater for the ocean after a juvenile riverine phase. At sexual maturity (around twenty-five years) it returns to the river to spawn, typically survives spawning, and then returns to the ocean to resume feeding. It may live up to 100 years or more and spawn repeatedly during its lifetime.

The shortnose follows a variation of that theme—it may or may not go to the ocean, and evidence suggests most do not, at least routinely. Important spawning areas in our river are the Enfield Rapids (Windsor, East Windsor, Windsor Locks, and Suffield, Connecticut) and below Turners Falls (Montague and Greenfield, Massachusetts).

Since the shortnose does not have to go to sea, dam-building created two spawning populations. Much of what we know about the lower river population came from the work of now-retired Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CTDEEP) biologist Tom Savoy. Much of what we know about the sturgeon between the Holyoke and Turners Falls dams is from the work of retired researcher Dr. Boyd Kynard and, currently, Dr. Micah Kieffer, both of the Conte Lab (US Geological Survey) in Turners Falls.

Dams were built at Enfield and Turners Falls in the 1700s. The Enfield Dam was first partial and then very low—sturgeon were probably able to get past it during most times. The Turners Falls Dam was beyond the fish’s historic range. But the Holyoke Dam, built in 1895, became a significant barrier that resulted in a lower river population that spawns in the Enfield Rapids and an upstream population that spawns in the Turners Falls rapids.

In the winter the fish drop downstream to congregate in deep water areas. For the lower river population, two such places are off Bodkin Rock (Portland, Connecticut) and Joshua Rock (Lyme, Connecticut). In the spring they move up to their spawning grounds.

The two sturgeon populations remained effectively separate until 2017. From the mid-1970s until 2016, sturgeon were lifted at Holyoke Dam, but the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), which manages the species’ recovery under the ESA, required the power company to capture them and release them back below the dam. The reason for this was that if they were allowed to pass upstream, there was a likelihood that individuals that returned back downstream after spawning would die while passing through the dam’s turbines. That changed when the owner of the hydro-project built a downstream bypass that was shown to safely pass sturgeon around the dam. Since 2017 between 20 and 100 sturgeon from the lower river have passed up over the Holyoke Dam annually and many have presumably spawned below Turners Falls, likely mating with fish that had been isolated in that upper population.

Shortnose sturgeon caught by an angler and released alive—the first documented report of a shortnose sturgeon in the Connecticut River upstream of the Turners Falls Dam, August 2017. Image Credit: NH Fish and Game and USGS.

In 2017 an angler posted a video of himself catching and releasing a large shortnose sturgeon, reportedly above the Turners Falls Dam—considered to be above the fish’s range. There had been anecdotal reports of other sturgeon observations above Turners Falls and even above the next dam (Vernon Dam just south of Brattleboro), but most experts had been skeptical of these reports. Dr. Kate Buckman, an ecologist with the nonprofit conservation group Connecticut River Conservancy (CRC), and James Gardner, a PhD candidate at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, decided to investigate the presence of sturgeon above the sturgeon’s accepted range by using eDNA technology.

Short for “environmental DNA,” eDNA reflects the fact that all living organisms constantly shed DNA into the environment, leaving telltale biochemical tracks of their presence behind. DNA can be found in waste products like urine and feces, sperm and eggs, mucus, or even byproducts of decomposing carcasses. Scientists have developed a tool to detect such DNA in the water at very low concentrations. Water samples are taken, amplified, and processed and then analyzed for the presence of DNA from the target species—in this case, shortnose sturgeon.

Kate and James took their first set of water samples in the early summer 2024 at various locations between Turners Falls and Bellows Falls. Results came back positive with many “hits” at four locations between Northfield, Massachusetts, and Westmoreland, New Hampshire, where there have been local reports of sightings. (See https://www.ctriver.org/post/edna-shortnose-sturgeon-connecticut-river.)

In September, Kate and James collected additional samples, and only one such “hit” (although a strong one) was detected at a new site between Turners Falls and Vernon. The sensitivity of the technology and strength of the signal varies for many reasons, including the amount of flow in the river and the amount of time since the sturgeon was in that location, etc. More analyses are required to clarify the results, and the CRC is seeking additional funds for future sampling. Based on these two sampling efforts, however, it seems clear: there are shortnose sturgeon upstream of the species’ accepted historic distribution. The number of fish is unknown.

Three possible explanations come to mind for their occurrence upstream of Turners Falls: 1) the species has been there since before the dams were built but eluded detection over the past 220+ years; 2) individual sturgeon ascended the Turners Falls and Vernon fishways and recolonized the area naturally; 3) someone moved them there. Veteran fish biologists, some of them retired after a long career, doubt the first theory. The states of Vermont and New Hampshire have regularly and extensively sampled the river (netting and recording captured species), and additional studies were mandated for the licensing and relicensing of Vermont Yankee and the hydroelectric projects. None of these efforts ever detected sturgeon. As for the second theory, sturgeon are notoriously poor swimmers and rarely use fishways. They’ve never been documented using the fishways at Turners Falls and Vernon. These fishways are monitored with video cameras, and it would be very hard to miss a sturgeon passing by the fishway’s observation window. Fish passage experts agree: there is no way a sturgeon went up the Turners Falls fishway. That leaves the third theory: Someone caught a sturgeon(s) below the Turners Falls Dam and released it above the dam(s).

How will this recent development guide the ongoing relicensing process for the hydro-electrical projects and Northfield Mountain Pumped Storage Facility? The CRC has submitted a comment letter to the Massachusetts DEP requesting that it consider this new evidence as it drafts its Water Quality Certificate as part of the relicensing process. (See https://www.ctriver.org/post/massdep-sturgeon-hydropower.) If there are sturgeon above Turners Falls, should the new Turners Falls fish passage facilities allow for the safe, timely, and effective upstream passage of shortnose sturgeon so the uppermost population can be reconnected with the lower two populations? Would the NMFS allow upstream passage as part of its sturgeon management plan since it doesn’t accept the upper river as part of the species’ natural range? Regardless of what is decided about passage, what is to be done about the sturgeon already upstream? Do they warrant protection under the ESA? It may depend upon the details of the listing, which occurred in the 1980s before more modern ESA processes were adopted.

During our recent conversation with Kate, she said, “Confirming the presence of endangered shortnose sturgeon in reaches of the Connecticut River where they were not considered to exist has exciting implications for gaining greater protections for the river and habitats that are important for the whole ecological community. CRC is actively working to engage in this research. More data will help us advocate for these amazing fish and further CRC’s mission to support clean water, healthy habitats, and resilient communities throughout the watershed.”

We applaud Kate, James, and the CRC for this novel work that has expanded our knowledge of migratory fish in the Connecticut River. As for the impact of this new information…? Stay tuned!

Steve Gephard is a fish biologist who retired from the CTDEEP and has a long association with the Connecticut River. Sally Harold has worked on dam removal and fish passage projects for over twenty years, including as Director of River Restoration and Fish Passage for the Connecticut Chapter of The Nature Conservancy. Steve and Sally collaborate on dam removals and fishway projects through RiverWork, LLC, and can be reached at Riverworkllc@gmail.com.