This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

Squish them. Squash them. Stomp them. Smash them. That’s been the order of the day from multiple government agencies inciting the citizenry to bring down the boot on any invasive spotted lanternflies they encounter. People throughout the Northeast have responded with gleeful bloodlust to stop the invasion of this gaudy planthopper native to Asia, ballyhooed as a multi-billion-dollar threat to crops and a befouler of homesteads.

Spotted lanternfly on the invasive tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima). Image Credit: Molly Schafer. Image Credit: Molly Schafer.

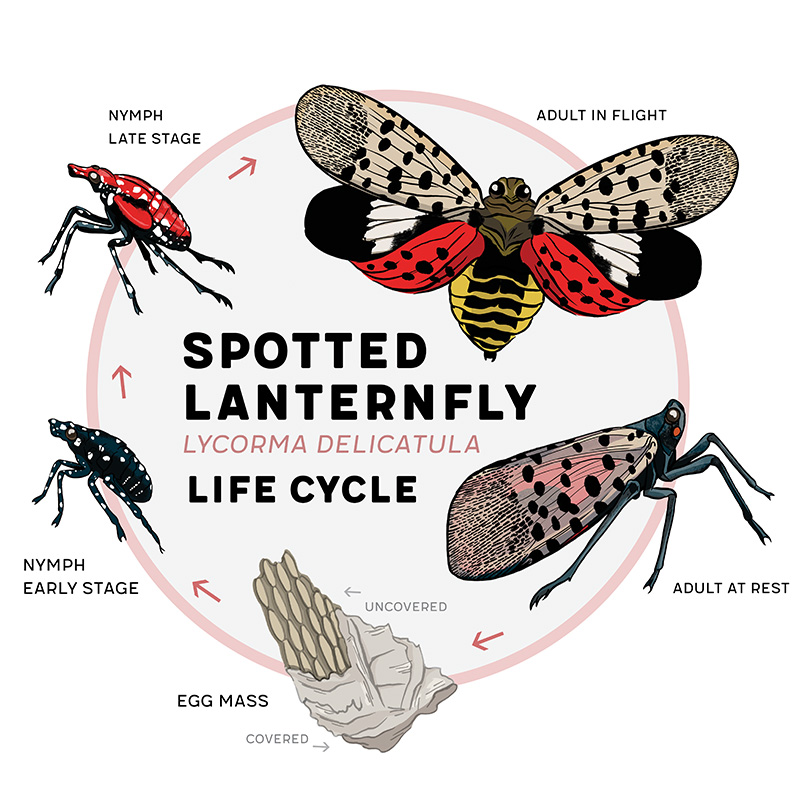

This so-called fly is really a planthopper approximately an inch long and one-half inch wide. The adult is so colorful it could make the most gorgeous of butterflies envious; its forewings are light brown with black spots in the center. The hind wings have contrasting patches of red and black with a white band in between. The legs and head are black; the abdomen is yellow with broad black bands. Its flashy display is warning coloration that discourages predators by advertising that it can be unpalatable as it picks up noxious chemicals from some of its host plants.

First detected in Pennsylvania a decade ago, the lanternfly spread like wildfire not because it’s a particularly good flyer but because its crusty, gray egg masses stick to almost any surface and readily hitchhike on planes, trains, and automobiles. Recent studies suggest nymphs and adults can literally hop a ride as well, but perhaps only for short distances.

The first lanternflies reported in Connecticut were in Greenwich, on the Purchase-New York line, not far from the Westchester County Airport. It has established itself in much of the Northeast, has shown up in the Midwest, and is predicted to ravage California vineyards by 2027.

Some scientists, though, are having second thoughts about whether the state-sanctioned slaughter and hysteria are merited. Their take on the threat posed by the lanternfly flies in the face of the panic that has erupted since it first appeared in Pennsylvania.

Some studies now suggest that lanternflies do less damage to trees and crops than originally thought. Typical of planthoppers, lanternflies use piercing, sucking mouthparts to penetrate and then siphon sap out of stems and branches causing wilting, leaf curling, and dieback. It feeds on more than 100 different plant species, from grapes to hardwoods.

Image Credit: Molly Schafer.

Feeding, says Kelli Hoover, professor of entomology at The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State), does not mean killing. Recent discoveries suggest trees and other plants attacked by lanternflies have a good chance of surviving, although the sooty mold they leave behind can disrupt photosynthesis and stunt growth. A fungus, the mold ruins the look and taste of fruit, such as grapes and apples. The lanternfly seems to be especially attracted to plants that have high hydrostatic pressure, the process by which water swells cells and keeps them firm, like a balloon. Grapes are one of these plants which, along with the lanternfly’s ability to travel, make vineyard owners nervous.

Other scientists wonder if predators might take a welcome toll on their numbers, lessening the threat. Also, lanternflies may be overly dependent on another noxious invader from Asia, the tree of heaven, which is their preferred host. Proving there is a little good in almost everything, the lanternfly may help control the tree of heaven, which crowds out native plants.

The tree of heaven, says Dr. Claire Rutledge, entomologist at the Connecticut Agricultural Research Station in New Haven, seems to be the only healthy, mature tree the lanternfly can kill outright. As for the long-term threat it poses, says Rutledge, “I have no crystal ball, but it may become only a nuisance pest, except to grapes.” That’s a big exception because the lanternfly can wipe out 90 percent of a grape crop in a heartbeat. “They suck grapes dry,” says Dr. Victoria Smith, Connecticut State Entomologist.

Whether such optimism is justified, if you live in northern or mountainous parts of the Connecticut River watershed a recent study suggests you are probably home free. It may be too cold for the lanternfly’s liking, although, as Smith notes, parts of its native range in China are as cold as, or colder than, here. Indeed, while freezing temperatures kill adults, eggs overwinter. A favorable climate may be one in which summers are warm enough for the lanternfly to complete its life cycle, during which it undergoes four wingless nymphal stages (instars) before becoming adults. “What we don’t know is how warm it needs to be for females to become reproductively mature and lay eggs,” says Dr. Julie Urban, researcher at Penn State, a pioneer of lanternfly research.

Urban is co-author of a paper recently published in the journal Environmental Entomology indicating that the ability of this invasive insect to develop through all stages and survive decreases as temperatures drop with higher latitude and altitude. It suggests that much of the Connecticut River watershed in Vermont and New Hampshire is out of bounds for the lanternfly, although a fine ribbon of potential habitat threads along the river’s shores. Essentially the farther north and the farther away from the river you live, the less chance lanternflies will attack your apples and excrete sugary honeydew that attracts bees and wasps and feeds black sooty mold, creating a noxious mess that defiles everything from lawn chairs to vehicles. So far, the insect has not colonized either state, but officials advise citizens to keep an eye out. Says Urban, “There will be pockets that are warm enough. So my sense is that there will be some areas where there would still be pockets of potentially high population numbers, and they could move into less permissive environments, especially as adults fly and move around in the late season.”

Massachusetts’ share of the watershed is much more vulnerable, with only the Berkshires and hills of the central portion of the state less hospitable to the lanternfly. It first showed up in the Bay State as a single dead adult in Boston in December 2018. The first established population was detected in Fitchburg in 2021. Last year, additional colonies began to pop up in the eastern, central, and western parts of the state, with colonies detected in Springfield in 2022 and last year in Agawam and Holyoke.

Except for a small area of the Litchfield Hills and Northwest Highlands, Connecticut seems at the invader’s mercy. Multiple adult populations were detected in Fairfield, Hartford, Litchfield, Middlesex, New Haven, and New London counties. The distribution of this insect continues to expand, says Rutledge.

The Penn State study used the concept of degree days (DD) as a basis for their calculation of the lanternfly’s ability to survive and thrive here. In entomology, a degree day is a measure of the time and extent to which temperatures are within the range that allows an insect to develop. If the average temperature on one day is, for example, ten degrees above an insect’s base threshold temperature for development, then ten-degree days are accumulated that day. Entomologists use accumulated degree days (ADD) to calculate the total heat demands an insect needs to grow through a stage or its entire life cycle. With ADD, scientists can peek into the hidden facets of insect growth and thus figure out the total heat demands required for survival. They’ve estimated the geographic range where spotted lanternfly can potentially complete a partial or full life cycle, from spring egg hatch to fall egg-mass deposition.

Researchers hope that the results of the study will enable them to accurately predict the geographic range of the spotted lanternfly. Scientists believe that the turning point for viable lanternfly reproduction is 991 ADD. In areas like the northern parts of the watershed, says Urban, the distance between habitat in which the lanternfly can or cannot reproduce may be very small. Areas in the Connecticut River Valley, she says, can have 500 more degree days than immediately adjacent uplands, so only a few miles may separate places shielded from lanternflies from those in which they can reproduce and cause damage.

All that said, the verdict remains out on how far the lanternfly will spread and how much damage it will cause. If research into the limiting effects of colder temperatures hold, however, lanternflies that voyage into the northern parts of the watershed may be heading into a dead end. Nevertheless, say researchers, stay vigilant and remember the Boy Scout motto to “Be Prepared,” just in case.

Ed Riccuiti is a freelance writer and published author who writes about history, nature, science, conservation, and law enforcement.