This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

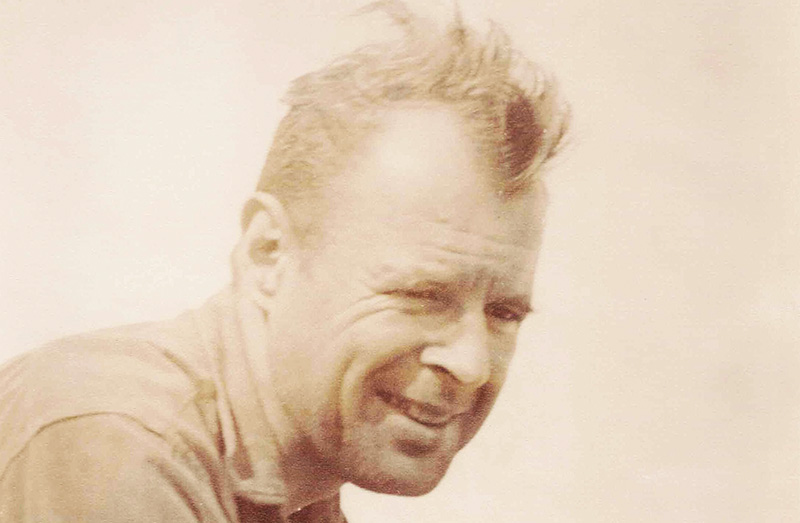

Ernest “Ernie” Feske. Photos courtesy of Ned and Carol Libby.

It was a lazy summer afternoon in the mid-1950s when Ernest Feske dumped a load of bricks into the Connecticut River.

Kersplash!

He and his wife, the Broadway actor Bettina Cerf, were wet and embarrassed, but otherwise OK, as was their boat.

A gaggle of bored adolescents were watching the New Yorkers screw up, shaking their heads as 500 bricks tumbled into the water off Essex Dock.

But Ernie Feske was not your average bumbling out-of-towner. He was a naval architect, and a member of Mensa who had been involved in the design of the amphibious Duck Boat, which had ferried American troops onto the beaches of Normandy a decade earlier.

Bettina was no slouch herself. In the 1940s and early ‘50s she acted in Broadway plays, and when she wasn’t on the stage, she was behind the curtains as a stage manager or casting director. Her credits included the smash Broadway debut of Oklahoma! in 1943.

Ernie and Bettina were hauling the bricks out to their island, Brockway Island, an elongated squiggle of land that separates Essex from Lyme on the far shore, like an ungainly comma. They were building a house on its eight precarious acres that previously had served only transients—that is, shad fishermen and duck hunters. The couple planned to live there year-round. No, these were not your average New Yorkers.

The island is named for the Brockways of Lyme who also have a ferry landing, a road, a reach on the river, and a popular wooden boat named after them. Brockways designed ships on the Connecticut River from the 1700s right up until the dawn of this century.

Brockway Island.

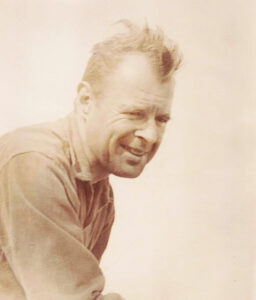

Ernie, still damp, surveyed the scene and challenged his smirking audience. “Who wants to make some money…penny a brick?” Ned Libby and David Hyde, two middle schoolers, stepped forward. Those steps would change the lives of the boys and the two adults profoundly, as few moments in time ever do.

The lads donned their trunks and dove in. It was the start of a beautiful, watery, lifelong friendship. The retiring couple had no children and found that they liked having Ned and David around. The boys were always looking for something to do, and an island smack dab in the middle of the mighty Connecticut River was a swell place to do things—or just lounge about. It beat the shore all to hell.

When the house was finished, Ernie spent a lot of time in the lower of the two floors, his drafting room, which occasionally was waist-deep in water. The boys came and went on weekends and even weekday evenings in the summer and during school, commuting in their boats. They’d watch Ernie work on his boat designs. They also helped around the place, cutting firewood, for example. They learned not to mess up an assignment. Ernie was easygoing except when he wasn’t.

But mostly they fished, swam, and explored the island. There was a beach on either side, separated by a mere 150 feet of terra (usually) firma. In high water, Ned could drive his outboard right across the island.

“When did you do your homework?” Ned was asked. “I never did homework,” he replied evenly. His classroom was the river, and he learned plenty navigating it, both days and nights, and watching Ernie patiently going about his business. Ned, now 81, turned out just fine. He started his own marine contracting business, did some shad fishing, and captained a river tug. David Hyde grew up to found Essex Hardware. He passed away in 2013.

Ernie and Bettina were not your average adults. Ned recalls spontaneous odysseys: “At 9 p.m. Ernie might say, ‘I could go for a cheeseburger,’ so we’d all jump in my boat, motor to Essex, get in his car, and drive to Wallingford because that was where the nearest McDonald’s was back then. We’d buy a bunch of burgers and milkshakes and get back to the island after midnight.”

Ned Libby and David Hyde.

Over the decades Ned would ferry necessities like kerosene and apple cider out to Brockway. “We bought a 30-gallon drum from E. E. Dickinson [manufacturer of Witch Hazel], and we’d go to a local cider mill and have them fill it up,” he says.

Ernie designed and built a unique one-seat hydroplane for Ned to zoom about the river in. “It had a very funny shape to it,” he recalls. “It looked just about like a big cello case. In the front where you’d sit, that would have been the big part of the case, and then it went narrow in the back where the engine was.” It could skip above the waves at about 30 knots.

“I had a lot of fun in it,” says Ned, who also learned a thing or two during its creation.

The winters on the island presented challenges, and opportunities, too. When the river froze hard, as it did back then, the couple would host skating parties for Ned and David and their no-longer-smirking schoolmates. Ned, by then in his late teens, would drive his truck out to the island. The couple also would drive to Essex and back in their much heavier Oldsmobile to shop.

Once, they didn’t make it.

“They lost their Olds in the river,” Ned recalls. “When the front end went through the ice, they panicked, and they opened both doors and jumped out, he and his wife. And as the front end went down the open doors settled the car on the ice. It sat there for quite a while. He was afraid to go back. Their groceries and ice skates were in the car.”

There were times when the couple got iced in and didn’t want to push their luck. One winter they passed the time learning how to speak Greek.

Bettina Cerf died first, of cancer. Ernie lived his last years at a house David owned on the mainland. The couple had no biological heirs. When Ernie died in 1994, he left the island to Ned and David.

Ernie and Bettina had registered the island as a federal seaplane base. Friends from New York would land there to visit, including Broadway types such as Basil Rathbone. Ernie was designing and planning to build his own seaplane, but never finished the project.

David and Ned, and their wives, children, and friends, continued to enjoy the island and rented it occasionally to sportsmen and vacationers. They built a new house with three bedrooms in 1995 to replace the old one. They introduced a flock of Guinea hens to keep the ticks at bay, but then along came the great horned owls; they picked them off one by one. “At nighttime, when it was dead still, their calls would make the hair stand up on the back of your neck,” Ned says.

In 2013, after David died, the island was sold to the Clark Group of Essex. The firm has rented it in recent years, but states on its website that its future is uncertain.

David Holahan is a writer, critic, and commentator.