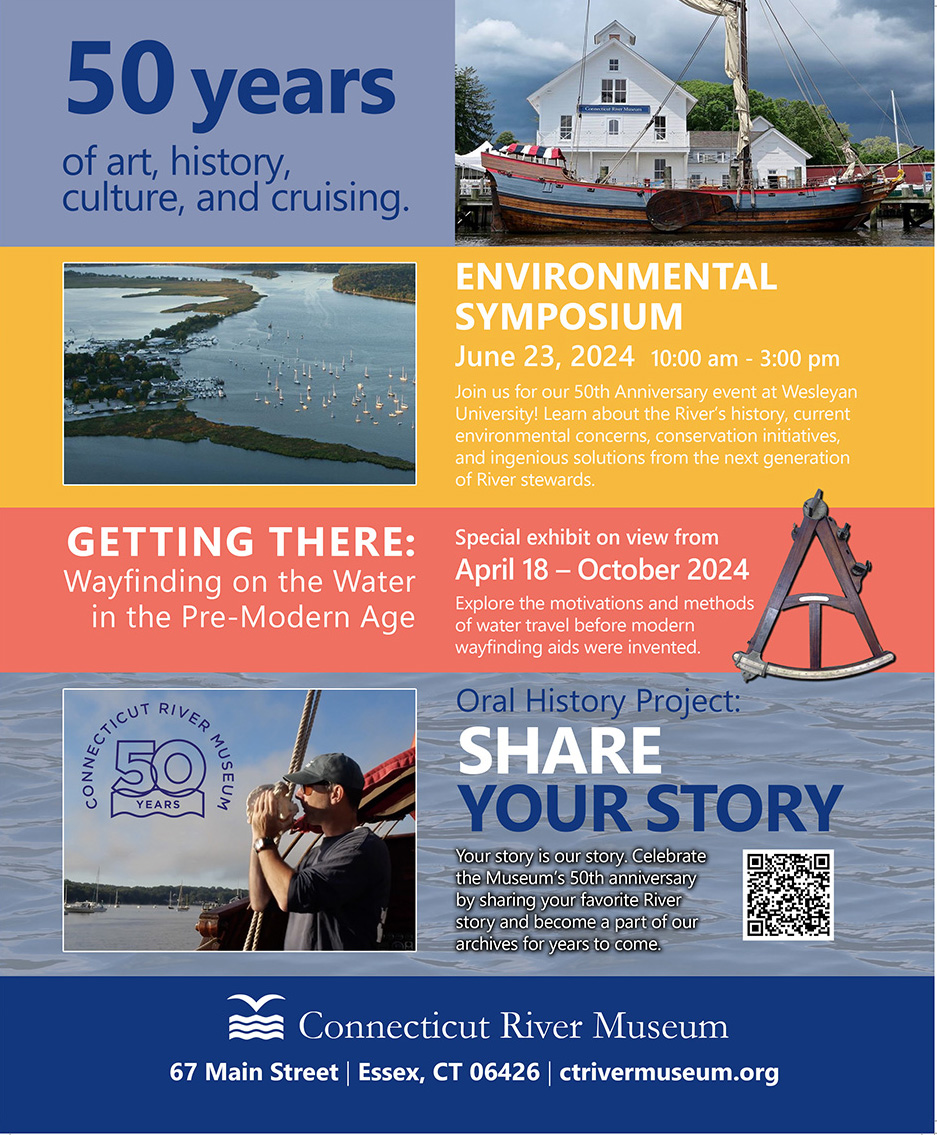

This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

This article appears in the Summer 2024 issue

The old Steamboat Dock building was restored to this pre-1930 footprint to become the Connecticut River Museum. Image Credit: Courtesy of Connecticut River Museum

During the 1970s the increasingly decrepit Steamboat Dock building at the foot of Main Street in Essex, Connecticut, was a topic of conversation for visitors and residents alike. For fifty years, from 1878 to 1931, steamboats served towns along the river, stopping at fifteen landings, loading and discharging cargo and passengers. Built in 1878 on the earlier Starkey’s Wharf, the building served as a warehouse for goods traveling by steamboat between Hartford and New York. Improved railroad connections, the rise of trucks for transporting goods, and the grim Depression economy doomed water transportation on the Connecticut River.

Mural of the Comeback River. Image Credit: Amy Trout

As the number of yachts in the harbor grew after World War II, though, the fabulous waterfront location made it a perfect site for a marina and chandlery. For a time both the Hartford and Middletown yacht clubs used the Steamboat Dock’s second floor as their downriver stations.

Later it was the Upper Deck Restaurant. The restaurant added seating with large windows and extended the building toward the water. By the 1970s the last tenant was a busy and noisy discotheque called The Backside Saloon—that is, until it was cited by the State of Connecticut for lack of proper sanitation. After that, the old Steamboat Dock became vacant and unsightly.

William G. Winterer and his wife, Vicky Winterer, purchased the Griswold Inn, just up Main Street, in 1972. Casting about for a solution to the nearby eyesore, Bill began talking with regular patrons about his plan to turn the building into retail shops with two attractive apartments upstairs.

Thomas A. Stevens, regional historian and former managing director of Mystic Seaport, strongly objected to privatizing what he considered “the most historic site on the Connecticut River.” A chorus developed that included Bob Wilkerson of Pequot Press, Connecticut author and filmmaker Ellsworth Grant, First Selectman Carl Ellison, New Era publisher Curtiss S. Johnson, and State Senator Richard Schneller. Over a shad dinner for sixty “stakeholders” at the Griswold Inn, a Steering Committee was formed to consider the feasibility of a nonprofit corporation to purchase the building and use it for community purposes.

Connecticut River Museum. Image Credit: Courtesy of Connecticut River Museum

Plans were formalized in 1974 through the creation of The Connecticut River Foundation at Steamboat Dock, a bicentennial project of several lower-valley communities. The aim was to preserve the historic landing, warehouse, and site on the Essex waterfront, and renovate the building.

The lead up to the Bicentennial of the American Revolution in 1976 created enthusiasm for community projects focused on preserving history that would last long after the fireworks faded. The foundation’s new board of trustees agreed to the creation of a museum.

The price for the property was negotiated down to $200,000, a considerable sum in 1974. Four banks split the loan, guaranteed by a group of trustees, and fundraising began. Every technique was employed: benefit concerts, river cruises, a costume ball, cocktail parties, and an antique auction. A planning grant from The National Endowment for the Humanities paid for restoration plans by architects Moore, Grover, and Harper, and for plans to transfer Tom Steven’s important research library to the chandlery and for future exhibitions. With those plans in hand and a grant from the State of Connecticut, work began in earnest. Excitement built when, on July 4, 1976, after a Bicentennial celebration in Town Park, the crowd followed the Sailing Masters of 1812 drum corps down to the Steamboat Dock where Governor Ella Grasso dedicated the future museum.

Objects, photographs, and even a ship’s log were donated; the chandlery was taken over as a temporary museum with a part-time director to manage it. I was hired as full-time director in 1979. A membership program was created. The board raised funds to renovate the Hayden Chandlery and create the Thomas A. Stevens Library. The library’s contents were given in his bequest when, unexpectedly, Tom died in 1982. Two years later the museum opened a first-floor exhibition to the public and dedicated an area of lawn where a potholed parking lot had long been.

The re-creation of David Bushnell’s Revolutionary War submarine, Turtle, found a permanent berth in the museum. Image Credit: Courtesy of Connecticut River Museum

By the organization’s tenth anniversary in 1984, there was a long-term exhibition on the second floor, a corps of volunteer Dock Keepers, a robust Winter Lecture Series, and a publications program underway. A growing collection of watercraft were housed in the Boat House built in 1987.

Today the museum serves some 25,000 visitors and over 3,500 students annually. School groups come from all parts of the state for interactive, engaging, and curriculum-based programs that support teachers with experiential learning. The acquisition of two vessels that put visitors and students out on the river was a huge game-changer—with a naturalist on board, the river and valley shore became an exhibition. Read on to find out more about how we’re growing and celebrating our 50th anniversary.

Getting There:

Wayfinding on the Water in the Pre-Modern Age

Sitting atop the 1848 Chart of the Bahama Banks and Gulf of Florida by Edmund Blunt is a 19th century spyglass and a pair of wooden calipers.

Image Credit: Courtesy of Connecticut River Museum

The Connecticut River Museum’s 50th anniversary presented an opportunity to look anew at our collections as we began to imagine navigating our next 50 years. Dan Thompson, the museum’s Captain and Watercraft Operations Manager, extols the virtue of asking three key questions when thinking about navigation: Where am I? Where am I going? and How do I get there? As it turns out, these were key questions for our institution as well. We began to answer the first of the three questions by diving into the archive of maritime historian Thomas A. Stevens’s bequest to the museum. Those objects and photographs became the inspiration for an exhibition focused on navigation—the coming and going of people to and from the Connecticut River valley—and also the answer to our second question.

This movement of people, some from thousands of miles away, took place over centuries when navigation was part art and part science—when water travel often meant sailing or paddling into the wilds of nature. Why would anyone take such risk—facing storms, getting lost, and encountering a multitude of dangers found in an unknown environment? The answers are what still motivate people today. But in the days before radar and GPS, the urgency and determination of getting there—safely and successfully despite the challenges—was profound.

The Middlesex in a Storm, by William K. McMinn, oil on canvas, 1853. Gift of William Wright, 2021. Image Credit: Courtesy of Connecticut River Museum

Getting there starts with the first navigators—the indigenous people who lived in the lower Connecticut River valley. For centuries the Nehantic, Wangunk, Podunk, and other River tribes took their dugout canoes along the waterways of the valley and into Long Island Sound for fishing, trade, and travel. Lucianne Lavin, author of Connecticut’s Indigenous People, called the rivers, streams, and sound “the major highways by which Woodland peoples communicated and traded.” Native Americans navigated by carefully observing celestial bodies, weather, geographic features, and wind direction and by “reading” the water. Today we call this “Natural Navigation.” For centuries people traveled confidently, using their experience and skills observing nature.

The Age of Discovery came to the Connecticut River when Dutch explorer Adraien Block sailed his small yacht, Onrust, upriver in 1614. For the Dutch, it was a time of exploration in search of raw materials for trade. They found what they were looking for in the abundance of fur-bearing animals in the Connecticut River valley, particularly Castor canadensis—the North American beaver. They established an outpost along the Connecticut River at present-day Hartford, called “Fort Good Hope,” to foster a peaceful and profitable trade with the Native Americans.

The river was not easy to navigate, however, as noted by Dutch envoy David DeVries in 1639 when he came to negotiate with the English settlers who were encroaching on the fort. “They cannot sail with large ships into this river, and vessels must not draw more than six feet of water to navigate up to our little fort….” Despite the river’s navigational challenges, it was a desirable place to live with ample natural resources, so much so that the English soon overtook the Dutch, who lost their claim to “the long tidal river.”

Settlers sought new markets for their farm and timber products. Motivated by the desire for the Caribbean specialties of sugar and molasses for the making of rum, enterprising colonists risked a voyage to explore this trade. In 1650 the Tryall, the first vessel built in the Connecticut Colony, was loaded with barrel staves and sent in search of trading partners. That voyage pioneered a trade between the Connecticut River valley and the Caribbean islands that benefited both regions for some 200 years—at the expense of tying the region’s economy to the developing slave economy in the colonies.

The Onrust, a replica of Adriaen Block’s boat that sailed up the Connecticut River in 1614, seasonally takes visitors out on the Connecticut River. Image Credit: Courtesy of Connecticut River Museum

In the 19th century, shipyards that had sprung up along the Connecticut River provided the shipping firms of New York with a variety of vessels. Merchants and mariners with ties to the river valley commanded many vessels making regular passage first to coastal ports and, then, to ports all over the world. They soon became veteran navigators, some of whose tools—quadrants, charts, telescopes, and the like—were passed down in families, and ended up in the collections of the museum. Through these objects, visitors will come face-to-face with the challenges of navigating through hurricanes, coral reefs, and treacherous fog without aid of modern technology. The insatiable drive to find new markets, new trading partners, and new resources has always and continues to motivate people along the Connecticut River who still must address the question of getting there.

The Connecticut River Museum’s 50th anniversary presents an important opportunity to reflect on our first five decades and to imagine our future. To that end, we have exciting programming planned over the course of the year. But first, let us consider the intertwined story of our river and the museum that tells its story.

Second floor gallery showing yachting and industry exhibits. Image credit: Amy Trout

As readers of Estuary know well, the Connecticut River represents a tremendous ecological success story. This would have seemed unlikely in the 1960s, when the river was filthy, unsafe, and clogged with sewage and industrial waste. Toxins and chemicals, especially DDT, were killing off eagles and osprey. Through the hard work and engagement of activists, students, politicians, and concerned citizens, the river was transformed. In 2012 it was named a National Blueway. Eagle sightings are now the norm rather than the exception on the museum’s popular river cruises, which run from February to October each year. But we are only able to continue to enjoy this tremendous riparian resource because, collectively, people made—and continue to make—choices to protect the Connecticut from abuse, runoff, and invasive species.

The Connecticut River Museum exists to tell stories that will inspire future generations of river stewards. We have a unique setting in our historic steamboat dock building overlooking the river roughly at the salt wedge, where the estuary gives way to fresh water. The museum takes seriously its responsibility to tell 12,000 years and 410 miles of history, through exhibitions, collections, and public programs.

Why does the work of a museum matter so much to the future of the river? In part because the river fell into such a polluted state when people ceased to pay attention and prioritized industrial use and transportation infrastructure at all costs. In places the river was covered by masses of highways and culverts, or was simply seen as a place to dump unwanted effluent. But the river has always been the backbone of New England.

Essex Auto Club Annual Car Show at Connecticut River Museum, September 2023. Image Credit: Elizabeth Normen

The museum gives voice to this ecological treasure that has impacted lives for millennia, that has shaped trade routes, given rise to industries, and in many ways given birth to the nation. By telling visitors about its history, we make people aware of choices—decisions that were made in the past and that must inform the choices ahead. It’s tempting in thinking about ecology to become stuck in binary thinking. And yet, part of the challenge of ecology—and a reason why museums are so suited to launching these conversations—is that stewardship is rarely black or white. Every choice has consequences, and we are all involved in those choices. To understand the Connecticut River, you need to immerse yourself in multiple vantage points, and to see the beauty and opportunity of every mile.

Whether you grew up coming to the Connecticut River Museum or have never been, we’d love to have you visit during this our 50th anniversary year. To mark this milestone, we launched an oral history project, in which we ask people to share their stories and memories about the river and the museum. It’s easy to do, and we want to collect as many stories from a range of experiences as possible—and I’d love it if you would take a moment to record your own thoughts and memories about the river. Find out more below.

On June 23, 2024, we’re hosting an all-day symposium at Wesleyan University—your chance to learn from experts and activists who are working to preserve the river from source to sound. We’d love to see you there (find out more on our website), and also at our community day—our Block Party—in September. I also invite you to visit our new exhibition, Getting There. We have lots of other programming—from lectures to summer camps to weekend activities for kids and adults, and of course, our ever-popular boat cruises on our eco-cruiser RiverQuest and our replica of Adriaen Block’s sailing vessel, Onrust.

Museums tell stories that breathe life into the past; they help visitors reimagine the world and their place in it. I see this every day when I watch children in our school programs learn that there is no minimum age required to be a citizen scientist. Indeed, everything we do is in service of our goal of helping people connect with the Connecticut River and to foster better stewards of the river by understanding the history of our choices to use and abuse it over the past millennia. I hope you’ll visit us soon and help us chart our course for the next 50 years and beyond.

Elizabeth Kaeser is the executive director, Brenda Milkofsky is founding director, and Amy Trout is curator of The Connecticut River Museum. Connecticut River Museum is a River Partner of Estuary magazine.

Resources

Getting There: Wayfinding on the Water in the Pre-Modern Age

On view through October 13, 2024

Connecticut River Museum

67 Main Street, Essex, CT

860-767-8269 | ctrivermuseum.org

Find more information about the symposium on June 23, 2024, and all museum events online at ctrivermuseum.org/events/.

Record your story about the river:

Visit ctrivermuseum.org/oral-history-project/ for instructions and a link to record your story.