This article appears in the Spring 2024 issue

This article appears in the Spring 2024 issue

Sally Harold releases salmon fry into the Jeremy River upstream of where the Norton Mill Dam was removed by a project that Sally managed. These tiny fry will live in the stream for two years before growing to six inches and heading to sea, where they spend another two years before returning as an adult. Image Credit: Steve Gephard.

Atlantic Salmon, a New England Icon

By Steve Gephard and Sally Harold

The Atlantic salmon is a near mythical creature, long prized by indigenous people, royalty, anglers, artists, and gourmands. It is found on both sides of the North Atlantic Ocean, and early English settlers to New England knew it well. During Colonial times the rivers in the British Isles were controlled by nobility, and salmon were reserved for the wealthy. Early settlers to New England could not believe their good fortune to have rivers full of salmon, theirs for the taking.

The cold-water-loving Atlantic salmon were only found in the New England English colonies and Canada. There were no salmon runs farther south, but historical accounts in the New England colonies/states abound in references to salmon. Today there remain many places named after the powerful fish, including places in the Connecticut River valley such as one Salmon River, several Salmon Brooks, and a number of Salmon Holes. The Connecticut River supported one of the largest runs of salmon in New England.

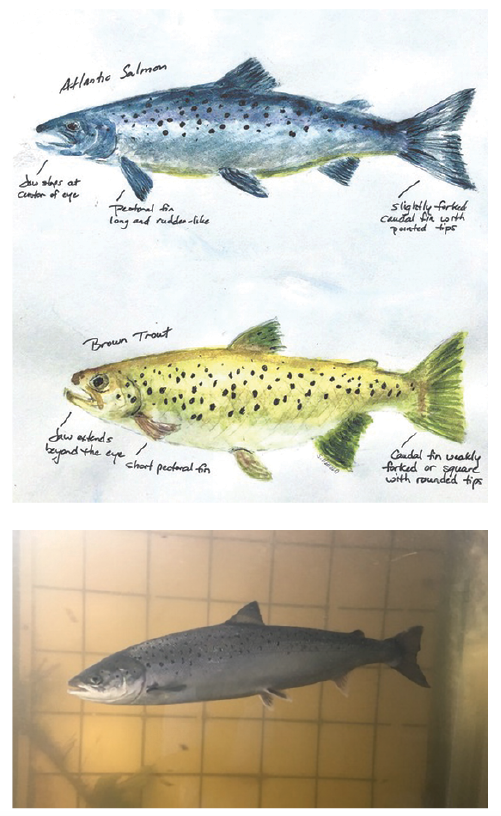

The Atlantic salmon is anadromous like American shad, sturgeon, river herring, sea lamprey, and others: they begin their lives in freshwater streams, living alongside and very much resembling trout (see accompanying sketch). After one to four years of juvenile life as a parr, they migrate out to sea as a six-inch smolt. There they feed, grow, and mature for one to three years and return as dazzlingly silver adults between 26 and 36 inches long. They return (home) to the same stream that they departed as a smolt due to their ability to memorize (imprinted to) the unique odor of their home stream. Moving upstream, they are able to power their way through heavy rapids and leap up to twelve feet in the air to surmount waterfalls. Salmon can go where few other fish can.

The Connecticut River was among the elite of the twenty-eight New England rivers that supported salmon runs, including the Merrimack, Saco, Androscoggin, Kennebec, and Penobscot and a number of smaller coastal streams. The Connecticut River lost its salmon run long before scientists started to study them and collect data, so we don’t know how many fish annually entered the river, but modern-day biologists have surveyed the amount of suitable habitat in the river today (more than any other New England river) and applied appropriate survival rates at the various life stages to estimate that at one time the watershed could have supported around 40,000 salmon a year.

The salmon were able to penetrate upstream nearly to the Connecticut lakes. A waterfall at the present-day site of Beechers Falls, Vermont, near Pittsburg, New Hampshire, finally stopped them. (Don’t look for the falls today. The logging industry blasted it out of existence to expedite the passage of rafts of logs.)

Top: Atlantic salmon and trout resemble each other. These sketches show how to distinguish them. The trout that is shown is a brown trout (most closely resembling an Atlantic salmon) but the features indicated for it also pertain to brook and rainbow trout.

Bottom: An adult Atlantic Salmon fresh from the ocean photographed through the viewing window of the Rainbow Fishway on the Farmington River in Windsor, CT. Each background square is six inches. Image Credits: Sally Harold (drawing). Steve Gephard (photograph).

Interestingly, the main stem of the Connecticut River does not provide suitable salmon spawning habitat downstream of northern Vermont and New Hampshire. The bulk of the habitat that produced young salmon was in the tributaries, which flowed east or west down the mountains and hills into the Connecticut. Notable salmon streams were the Salmon, Farmington, Chicopee, Westfield, Deerfield, Millers, Ashuelot, West, White, and Ammonoosuc, but plenty of other smaller streams all the way up to the Northeast Kingdom also supported salmon. Most of these streams had rapids and falls that stopped shad, but salmon were able to leap these barriers and reach habitat far upstream. Exceptions may have been the Sugar and possibly the Black rivers. Bellows Falls, Vermont, was not so much of a classic waterfall as an incredibly powerful gorge or chasm that stopped most fish. The conventional wisdom is that the falls even stopped small salmon and only the really big, powerful salmon (30–40 pounds) could muscle their way through the tumultuous waters and reach the upper river. There’s reason to believe that some of these larger salmon entered the river months earlier than the typical April–May window, so that they had time to move through Bellows Falls before the heavy spring freshet. An ad in an Old Saybrook newspaper in the 1700s advertised the first salmon of the season—in December. That fish would not have spawned until the following October.

Indigenous people from all over the Northeast—not just the Connecticut River tribes—came to the river to fish for salmon. Mohawks were known to visit favorite fishing sites such as Bellows Falls, Turners Falls, and Hadley Falls. These early fishers subsisted on shad and lamprey but smoked and dried the salmon to take back to their villages. Early settlers frequented the same locations but later also used boats and nets to catch salmon and shad in the lower river. There are all sorts of legends about landings, including the oft-told yarns that indentured servants were fed so many salmon they complained, and that netters insisted that buyers of shad had to buy salmon as well to take them off their hands. The historical record, though, is full of conflicting and borrowed accounts, so it is impossible to separate fact either from fiction or, at least, exaggeration.

The Connecticut River lost its salmon incrementally in the Colonial period as settlers in Connecticut and Massachusetts built dams on the tributaries for ice ponds, sawmills, and gristmills. This practice spread north, and by the time of the Revolutionary War, most streams in the two colonies were completely dammed and devoid of salmon. Much of Vermont and New Hampshire were lightly settled or downright wild, and all of the returning salmon continued to spawn in that northern area. The Industrial Revolution resulted in the construction of larger dams to power large-scale manufacturing. In 1798 the first dam across the main stem Connecticut River was built just upstream of the present-day site of the Turners Falls dam. It was the engineering marvel of the world—reportedly the largest dam in the world—but it blocked all salmon from reaching the last remaining spawning habitat, and by the War of 1812, no more salmon entered the river.

In the 1860s early conservationists who were returning to New England from the Civil War initiated a restoration program creating the nation’s first state fish and game agencies in our four states to oversee the effort. This was about the time that increased leisure time gave rise to sport fishing in the US. The agencies imported salmon eggs from Maine, but Connecticut was unable to stop the netting of salmon in shad nets, Massachusetts was unable to construct effective fishways at dams, and the effort failed.

A second restoration effort began in 1967, fueled again by four-state cooperation, federal funds, and improved scientific understanding and technology. Fishways were built at the dams at Holyoke, Turners Falls, Vernon, Bellows Falls, and Wilder (by then all of these had become hydroelectric dams), and a modern salmon hatchery was built at Bethel, Vermont. Hundreds of salmon returned annually but then returns declined. After Tropical Storm Irene damaged the Bethel Hatchery in 2012, the program ended. Books can be written about this program, but the essence of its lack of success likely lies with climate change.

The State of Connecticut still stocks a few salmon fry out of one of its hatcheries into the Salmon and Farmington rivers as part of its so-called Legacy Program. So there are still young salmon found in these streams, but every year fewer than ten adults return to spawn. They are no longer retained at fishways but allowed to continue upstream. The program also supports a very popular educational program run by the Connecticut River Salmon Association called Salmon-in-Schools, in which the State of Connecticut gives 200 fertilized salmon eggs to each of 50 or so schools. Students incubate and hatch them, and eventually stock the fry into those two rivers, all the while learning about salmon, rivers, ecology, and conservation. It is unlikely we’ll ever see significant numbers of Atlantic salmon in our watershed again, but it is important to remember this species that was so important to the river, to teach our children, and to use these fish as a cautionary tale so that under our watch we strive to never lose another species.

For more information about the Salmon-in-Schools program, visit ctriversalmon.org.

Steve Gephard supervised Connecticut’s participation in the Connecticut River Atlantic Salmon Restoration during his long career as a fish biologist with the Connecticut Fisheries Division. He continues to serve as a US Commissioner to the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization.

Sally Harold worked on dam removal projects that benefitted salmon restoration when she worked with The Nature Conservancy.