Odds are that most hikers who traverse Connecticut’s Metacomet Trail along a spectacular trap rock ridge west of the Connecticut River have little idea that both trail and ridge are named after the Native American chief who in 1675 started a resistance that—if it had been successful—could have emptied New England of English colonists. That’s because Wampanoag Sachem Metacomet (or Metacom) is better known as King Philip, the name the English gave him and which label was assigned to the war that almost nipped their colonization in the bud.

Although, until recently at least, King Philip’s War has been pretty much a historical footnote, it is arguably the goriest war in the nation’s history, with more casualties per capita than any other. By comparison, the renowned Geronimo’s raids and Crazy Horse’s defeat of Custer were minor skirmishes swamped by the tide of Manifest Destiny. By then, the fate of Indigenous people had been decided, given they were up against an enemy armed with the power of the industrial revolution.

In 1675 on the other hand, English colonists were just beginning to extend their toehold in New England, only a few years removed from rude settlements on the knife’s edge of survival. Their military technology had barely emerged from the late Medieval, although the transition from primitive matchlock firearms to flintlock significantly increased their firepower. As often noted, the most telling weapon in the European arsenal was the diseases they transmitted to the vulnerable Native populations, which severely weakened their fighting strength. Even so, Native warriors, who readily adopted English weapons, came within a hair of final victory—in part because the colonists were slow to move away from a European style of warfare.

Philip, King of Mount Hope,” from The Entertaining History of King Philip’s War, by Thomas Church, engraved by Paul Revere, 1772. Image Credits: Getty Images/LeitnerR (brown background). Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale Art Gallery/Public Domain (King Philip). Getty Images/PANGGABEAN (geometic patterns).

King Philip’s War was a bigger, bloodier epilogue to the Pequot War that four decades earlier opened the door to colonization of the Connecticut River Valley, engaging some of the same protagonists. Metacomet was the titular head of what became known as the Wampanoag but was really a decentralized confederation of tribes that included the Pokanoket and Pocasset (part of the Wampanoag), Nipmuc, Pocumtuck, Abenaki, and many other smaller tribes. As in the Pequot War, the powerful Mohawk of New York and Mohegan under Sachem Uncas in Connecticut tipped the balance by siding with the colonists. Rhode Island’s Narragansett, who had also allied forty years earlier with the English against the Pequot, reversed course and joined the uprising after the English foolishly attacked them in a preventative strike.

King Philip’s War is a conflict laden with the tragic irony that the son of the man who had helped the Europeans was forced into war against them. Metacomet was the son of Massasoit, Wampanoag supreme sachem, perhaps the most revered Indian in American history books for befriending the Pilgrims and helping them survive for the first forty years in their harsh new world. Recognizing that native life would never be the same, Massasoit brokered the best deal possible for his people by supporting the English against other native groups, especially the Wampanoag’s foes. About the same time, in Connecticut, Uncas had made the same decision, helping the English nearly destroy his rival, the Pequot, and keeping the Narragansett off his back.

That in a couple of generations people who supposedly gathered amiably around the first Thanksgiving table could be slaughtering each other with gusto testifies to the fact that the alliance between Massasoit and the colonists was a marriage of convenience, headed for divorce. The English never thought of the Native people as equals. Prevailing Puritan ethos, in fact, cast Indians as subhuman, idolaters, even agents of Satan, although perhaps it was as much a cover for grabbing Indian land as a religious tenet. The Native peoples, for their part, were just as desirous for European goods and used the colonists against rival tribes, until they realized the ultimate price.

Tensions had smoldered for years as the Wampanoag—and tribes across New England—were forced to cede more territory to the colonists’ insatiable demand for land. The gasoline that fueled the conflagration was the suspicious death in January 1675 of a Christian Indian, John Sassamon, a one-time Harvard student and former advisor to Metacomet’s late older brother, no less, after he reported to the English that Metacomet was cogitating an uprising. In response, after a show trial, the colonists hanged three Wampanoag leaders for Sassamon’s murder. In retaliation, within a few days the Wampanoag fell upon and burned Swansea, on the border of their territory in eastern Rhode Island and southeastern Massachusetts.

From then on, ineffectual negotiations ran parallel with bloody tit for tat as the colonists destroyed Metacomet’s home base at Mount Hope, Rhode Island. It did nothing to slow down the Wampanoag leader. As other tribes and bands gathered under his banner, settlements throughout Plymouth Colony were attacked. Assault on settlements spread like a wildfire from southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island up the Connecticut River Valley into the interior. Back on their heels and realizing that a small uprising had grown into a region-wide crusade, on September 9, 1675, all colonies in Massachusetts and Connecticut, as the New England Confederation, formally declared war against their assailants. (Rhode Island remained neutral.)

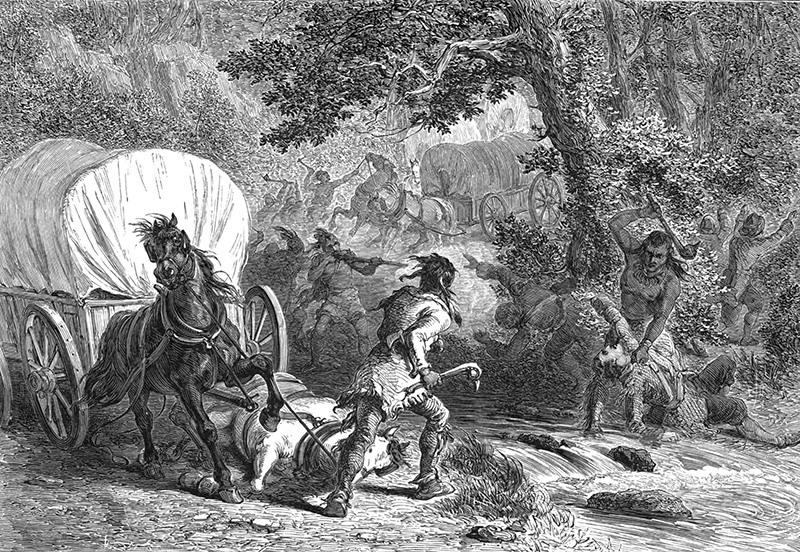

“Battle of Bloody Brook” engraving, artist unknown, Pioneers in the Settlement of America by Williams Crafts, Published by Samuel Waker & Co. 1876. Images Credit: Wikimedia, Public Domain.

A few weeks later, the colonists suffered a horrendous defeat in a battle that has been memorialized in a ballad that mourns, “Oh, weep, ye Maids of Essex, for the Lads who have died, […] The Bloody Brook still ripples by the black Mountain-side.” The song recounts how on September 28, 1675, an English militia contingent (including men from Essex County, north of Boston) blundered into an ambush in South Deerfield by Connecticut River tribes while escorting wagons loaded with corn. More than sixty men died in the attack by several hundred Indians.

As Indians hit again and again, the boundaries of colonization shrank as terrified settlers pulled out of Massachusetts towns from northwestern frontier outposts of Northfield and Deerfield on the Connecticut River’s banks, to Rehoboth and Dartmouth on the southeastern coast, near the colonial heartland. War parties advanced to within ten miles of Boston, where frightened residents considered building a palisade to protect the city.

Meanwhile, the formidable Narragansett, 3,000 warriors strong, had stayed neutral—that is, until the English, fearing they would choose a side—i.e., the wrong one in their estimation—destroyed the Narragansett’s main encampment. On December 19, 1675, more than 1,000 militia and Mohegan attacked the main Narragansett stronghold inside a frozen swamp in West Kingston, Rhode Island. Many warriors were away fighting. Inside were mainly women and children, including Wampanoag refugees. They were butchered, many burned alive as colonists destroyed the village. By some estimates, about 300 Indians and fewer than 100 militiamen died in what is known as the Great Swamp Fight.

Led by their chief Canonchet, the remaining Narragansett attacked Old Rehoboth and set Providence ablaze. Almost wherever the colonists turned, Indian raiders wrought havoc. By April 1676, however, an English party caught Canonchet and turned him over to Uncas, who had him shot, beheaded, and quartered.

Metacomet was also having his problems. Shortly after the Great Swamp Fight, he led 500 warriors into New York, hoping to enlist Mohawk aid. The Mohawk not only rebuffed but attacked him, killing most of his warriors. It was a turning point. Although they would fight on for a while, Metacomet and his allies were finished.

“Death of King Phillip” engraving, artist unknown, Pioneers in the Settlement of America by Williams Crafts, Published by Samuel Waker & Co. 1876.

The deciding blow fell in May 1676 when militiamen and Mohegans attacked a sleeping Native village at Turner’s Falls on the Connecticut River where women and children of Narraganset, Wampanoag, and other tribes had fled to from the south. As customary in war, the warriors were encamped a mile away, but soon joined the battle. With the slaughter at Bloody Brook on their mind, the colonist attackers showed no mercy, killing women and children at will. The Indians mounted a retaliatory strike against Hatfield days later. Nearly 1,000 colonial and allied Native troops from Connecticut and Massachusetts responded by early June. These would be the last coordinated Native attacks in the Connecticut River Valley. At least 200 Indians died, as did about 60 colonists.

Grave marker near the Bloody Brook Monument, South Deerfield, MA. Image Credit: Daderot via Wikimedia Commons/CC0 PD .

Although clashes continued, Native resistance faltered, with many Indians taking advantage of amnesty offered by the English and some tribes signing peace treaties. By midsummer, mass surrenders were occurring and Metacomet had holed up secretly near Mount Hope. A traitor among Metacomet’s men tipped off the English, who, in August, cornered him in a swamp, ironically near where John Sassamon’s body had been found, triggering the entire war. Metacomet was shot through the heart by a Christian Indian in the English party. He was quartered and his head skewered on a spike to be displayed at Plymouth. His wife and son, along with myriad other natives, were sold into slavery in the Bahamas, where some residents today trace their ancestry to the Indian captives.

Had it not been for the pro-English sympathies of the Mohawk in the north and Mohegan in the south, the history of the region that birthed the American Revolution might have been drastically different. As it was, the New England colonies barely escaped collapse. Native warriors had destroyed or ravaged three dozen towns, half of New England including Springfield and Providence, which they burned. More than 1,000 settler homes were destroyed. In fourteen months, the war claimed about 600 settlers and thousands of Native people. Plymouth Colony alone lost eight percent of its adult males. The explosive violence left the region’s colonies and economy in a shambles, although Connecticut, focus of the Pequot War, was spared the worst because of its alliance with Uncas and the substantial forts built in the Pequot War.

English victory broke the back of Native resistance to colonization in New England. Native tribes were destroyed or greatly diminished. To be sure, New England frontiers suffered Indian raids in subsequent conflicts with the French. However, in the French and Indian War, except for northern New England, most Native combatants were from tribes serving as mercenaries for the French in Canada, not locals defending their own land.

Bloody Brook Monument erected in 1838 in South Deerfield. Image Credit: Tom Walsh via Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

King Philip’s War influenced American history well past its end. It reinforced the take-no-prisoners, give-no-quarter conviction that from then on characterized Euro-American dealings with Native tribes. And yet a number of the New England tribes survived, held onto territory, and enjoy a measure of sovereignty today. The war also forced independent, sometimes competing, colonies to work together in their own defense, which would serve well starting on an April morning a century later.

Ed Ricciutti is a veteran journalist and author. He writes mainly about nature. He has written for the Hartford Courant, Science Digest, Field & Stream, Wildlife Conservation, and Fly Rod & Reel. He has published 80 books. He practices what he has preached as he has fished and hunted all over the world. His stories smack of having “been there, done that.”