Lydia Sigourney

Lydia Sigourney

The Sweet Singer of Hartford

By Wick Griswold

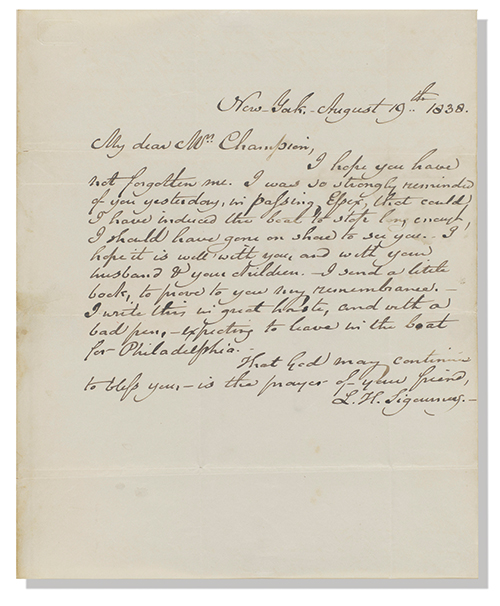

In 1831, Amelia Champlin, wife of Captain Henry Champlin, Master Mariner from Essex, Connecticut, wrote a letter to her dear friend Lydia Sigourney. She posted it up the river to Hartford on a steamer. She asked Lydia to compose a poem in memory of her recently deceased 3-year-old daughter, Louisa. The result was “Lost Darling,” one of thousands of memorials that Sigourney wrote in her career as a prominent female author of the 19th century. Virtually forgotten today, Lydia published dozens of books and hundreds of magazine articles. High childhood mortality rates assured her an ongoing audience for elegies, but she also wrote self-help treatises, history, etiquette, and social commentary. Her poetry spanned an eclectic array of subjects, including the riverscape she shared with her close friend, Amelia.

In 1831, Amelia Champlin, wife of Captain Henry Champlin, Master Mariner from Essex, Connecticut, wrote a letter to her dear friend Lydia Sigourney. She posted it up the river to Hartford on a steamer. She asked Lydia to compose a poem in memory of her recently deceased 3-year-old daughter, Louisa. The result was “Lost Darling,” one of thousands of memorials that Sigourney wrote in her career as a prominent female author of the 19th century. Virtually forgotten today, Lydia published dozens of books and hundreds of magazine articles. High childhood mortality rates assured her an ongoing audience for elegies, but she also wrote self-help treatises, history, etiquette, and social commentary. Her poetry spanned an eclectic array of subjects, including the riverscape she shared with her close friend, Amelia.

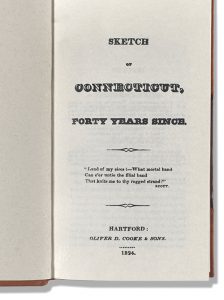

Lydia Sigourney’s “The Connecticut River” isn’t the best poem ever written about that waterway, but it’s one of the longest. The style is stuffy, some themes are dated, and she does go on, but currents of her wisdom still resonate. Sigourney appreciates the Connecticut’s place in the world’s riverine hierarchy. She ranks it with the St. Lawrence, the Nile, the Ganges, and the Rhine. She rhapsodizes about an era of agrarian bliss. Its river banks are peopled by industrious families who work harmoniously to engender bountiful crops and happiness. Sigourney’s words value freedom and democracy. They denounce despots and slavery. Her stanzas portray women equal to men as they toil together. She bemoans the fate of Indigenous people whose canoes no longer grace the river. Gender dynamics, a hatred of slavery, and anger over the fate of Native Americans recur throughout her work. She also wrote, perhaps, the first poem ever about a steamboat ride on the Connecticut.

Today, the Sweet Singer of Hartford’s name is most often read on Sigourney Street signs in that city’s west end. She is cast into a limbo of bygone literati, no longer cited much or celebrated. Once she was the most famous woman writer in the United States, and there are inklings of renewed interest in her work. Born in 1791, she was the daughter of a handyman named Huntley and his wife in Norwich, Connecticut. Her father’s employer, a widow, took a liking to young Lydia and saw that she was well-educated. She introduced her protégé to the influential Wadsworth family in Hartford. This serendipitous circumstance provided an entrée to her writing career.

Today, the Sweet Singer of Hartford’s name is most often read on Sigourney Street signs in that city’s west end. She is cast into a limbo of bygone literati, no longer cited much or celebrated. Once she was the most famous woman writer in the United States, and there are inklings of renewed interest in her work. Born in 1791, she was the daughter of a handyman named Huntley and his wife in Norwich, Connecticut. Her father’s employer, a widow, took a liking to young Lydia and saw that she was well-educated. She introduced her protégé to the influential Wadsworth family in Hartford. This serendipitous circumstance provided an entrée to her writing career.

She created a school in Norwich to teach children from impoverished families and African Americans. Over 200 years ago, this was a bold undertaking. She then moved across the river to Hartford and, with the backing of the Wadsworths, established a school for girls in 1814. Her educational focus was ahead of its time. Rather than concentrate on traditional “feminine” subjects, the curriculum highlighted math, literature, philosophy, and history. She was among the first to teach deaf children to read and write English. Her work solidified a commitment to gender equality, although it would be tested in the future. With the help of Daniel Wadsworth, she published “Moral Pieces in Prose and Verse.” It was well received, and young Lydia Huntley gained renown as an educator and a writer.

She created a school in Norwich to teach children from impoverished families and African Americans. Over 200 years ago, this was a bold undertaking. She then moved across the river to Hartford and, with the backing of the Wadsworths, established a school for girls in 1814. Her educational focus was ahead of its time. Rather than concentrate on traditional “feminine” subjects, the curriculum highlighted math, literature, philosophy, and history. She was among the first to teach deaf children to read and write English. Her work solidified a commitment to gender equality, although it would be tested in the future. With the help of Daniel Wadsworth, she published “Moral Pieces in Prose and Verse.” It was well received, and young Lydia Huntley gained renown as an educator and a writer.

In 1819, she married Charles Sigourney, a Hartford widower. She closed her school but kept putting pen to paper. This led to contention. Her husband didn’t approve of her writing. She wrote anyway, but Charles didn’t make it easy. She initially published anonymously. Lydia produced prose and poems. She used what money she made to help her parents and aid charities. Temperance, missionary work, and war relief were her favorite causes. Charles railed against her writing. He once chuffed that “If she were less of a poet, she would be more of a wife!” But her chastening spouse softened his opposition when his economic situation deteriorated and Lydia’s income became critical to keep their household intact.

In 1819, she married Charles Sigourney, a Hartford widower. She closed her school but kept putting pen to paper. This led to contention. Her husband didn’t approve of her writing. She wrote anyway, but Charles didn’t make it easy. She initially published anonymously. Lydia produced prose and poems. She used what money she made to help her parents and aid charities. Temperance, missionary work, and war relief were her favorite causes. Charles railed against her writing. He once chuffed that “If she were less of a poet, she would be more of a wife!” But her chastening spouse softened his opposition when his economic situation deteriorated and Lydia’s income became critical to keep their household intact.

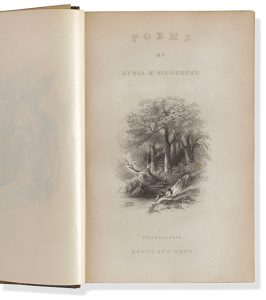

She began to publish under her own name. Sigourney was a shrewd businesswoman and negotiated favorable contracts. She wrote school texts and etiquette books. Some of the advice she imparted to young women was at odds with her early feminism, but it sold well. In addition to self-improvement books, Sigourney churned out reams of poetry. Her rhymes aligned with the ethos of her era, their patriotic and religious themes found eager audiences as did her talent for death-related work. Her combined successes led her to be among the first women to have a significant career as a professional writer in the United States.

She ran into harsh criticism from male peers. No less a scribbler than Edgar Allen Poe called her “a determined imitator.” He claimed she cannibalized the works of others and passed them off as her own. Poe had to walk back his vitriolic remarks when their publisher reminded him that her immense popularity basically kept their magazine in business. Another peccadillo that irked colleagues was her intimations that mere acquaintances among literary elites were her close friends. She often inflated her importance with an eye towards enhanced branding and increased sales. Her exaggerated self-promotion notwithstanding, Sigourney is credited with opening corporate publishing to women. At one point, Godey’s Magazine paid her just to stick her name on its masthead. She is acknowledged as a pioneer who inspired women writers to seek and attain commercial success.

Today academic interests in Lydia Sigourney focus on her trail-blazing, gender sensibilities and vehement opposition to slavery and racism. She was an ardent, lifelong abolitionist. Her awareness of the terrible injustice wrought upon Indigenous people finds renewed notice on area campuses. In several poems, she mulls over the poignant irony that after they appropriated land and water from Native Americans, European transplants continued to use their original designations. She cites Connecticut and the Connecticut River as prime examples. A verse from her poem “Indian Names” delineates this cultural appropriation.

Their light canoes have vanish’d

From off the crested wave…

But their name is on your waters

And you may not wash it out.

One might hope that the Sweet Singer of Hartford will enjoy a renaissance. Perhaps not as a great poet but as an integral part of America’s literary history and tradition. It is only fitting that she should be acknowledged pride of place for her efforts that prompted women and girls to take up the pen and contribute to our canon of the written word. One might further hope that the city on the banks of the Connecticut River that inspired her sobriquet will also revivify and flourish as the future unfolds, engendering new dimensions of community, diversity, and spirit that Lydia Sigourney would applaud.

Renwick (Wick) Griswold is a noted author and Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Hartford. His signature course is the Sociology of the Connecticut River. He is an associate producer of the documentary Ferry Boats of the Connecticut River. He also hosts Connecticut River Drift on iCRV Radio in Ivoryton, CT, and is Commodore of the Connecticut River Drifting Society.