Chapter 1: The Rescue

I put my hand out in front of me like I’m offering to shake and say: “How do you do, sir. I’m called JJ, just like my father, and his father, and his father before him. We’re all ferrymen here in Old Saybrook, and we’re all called JJ.”

Oh spit! What I just said, that’s not a whole truth. Cap—he’s my father—Cap says never start out with a lie when you first meet a man because he’ll never believe a thing you say from then on. Truth is I’m not a ferryman yet because I’m thirteen, but when Cap decides I’m old enough and I’ve learned enough, I will be. It’s not a law; it’s just the way it is here on the Connecticut River: father-to-son, father-to-son, all ferrymen. No boy in my family named JJ ever thought of being anything but a ferryboat captain.

Until me.

I jump nearly out of my boots when my cousin Ray comes up behind me and says, “Who you talking to, JJ?”

“Oh, nobody, really.”

“You in the practice of offering to shake hands with nobody?”

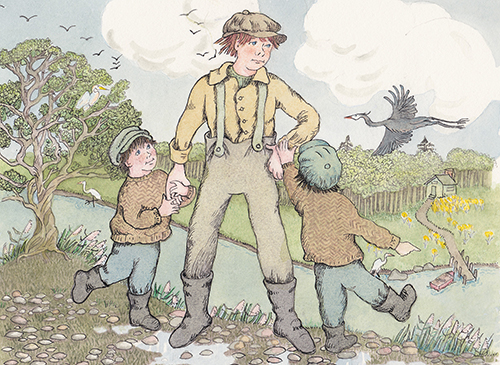

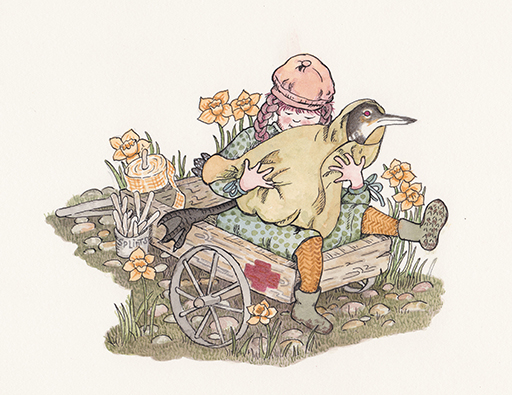

Three houses, all side-by-side, all close relations. Ray’s father and mine are brothers and live in side-by-side houses; Grandfather JJ to both Ray and me lives alone in the third house. Lots of other relatives live on streets near here, but they aren’t all ferrymen. Many of the ladies, who are the mothers, come from fine houses upriver, the sort of house with a library and stained-glass windows. The kids you might see on these streets here are likely my cousins of one rank or another.

Ray joins up with me most mornings, and we head off together to some place we need to be—like the ferry landing, school, or church—or someplace we don’t need to be, which is always more fun.

“Talking to Nobody, JJ?”

“Never you bother, Ray. I’m practicing asking a man about a job.”

“I keep reminding you, you got a job; you’ll be a ferryman, just like me.”

“Come on, Ray, haven’t you ever at least thought about doing something else? With all the talk about building a bridge across the river, right here, well, if they build that bridge before we get any older, we’ll be left without a job.”

“Unless the river washes that bridge away; you watch, JJ, just who they come running back to when they gotta get across that river.”

“Even so, you and me, Ray, we’re probably the last. I’m just thinking about what I might do if I knew I wasn’t going to be a ferryman.”

A little voice shouts up to us from down below, by the river bank, “Can you help us, JJ? Please?”

Adam and Ben, 5-year-old twin boys; Clara, their 6-year-old sister. The boys are struggling to pull their cart up to the road; Clara sits inside the cart; she’s hugging something all swaddled in a blanket. Ray, who has 7 brothers and sisters, says, “You go. I already broke up two punching fights this morning in my own house and that was before I even finished my porridge or put my boots on. I’ve done my big brother work for one morning.”

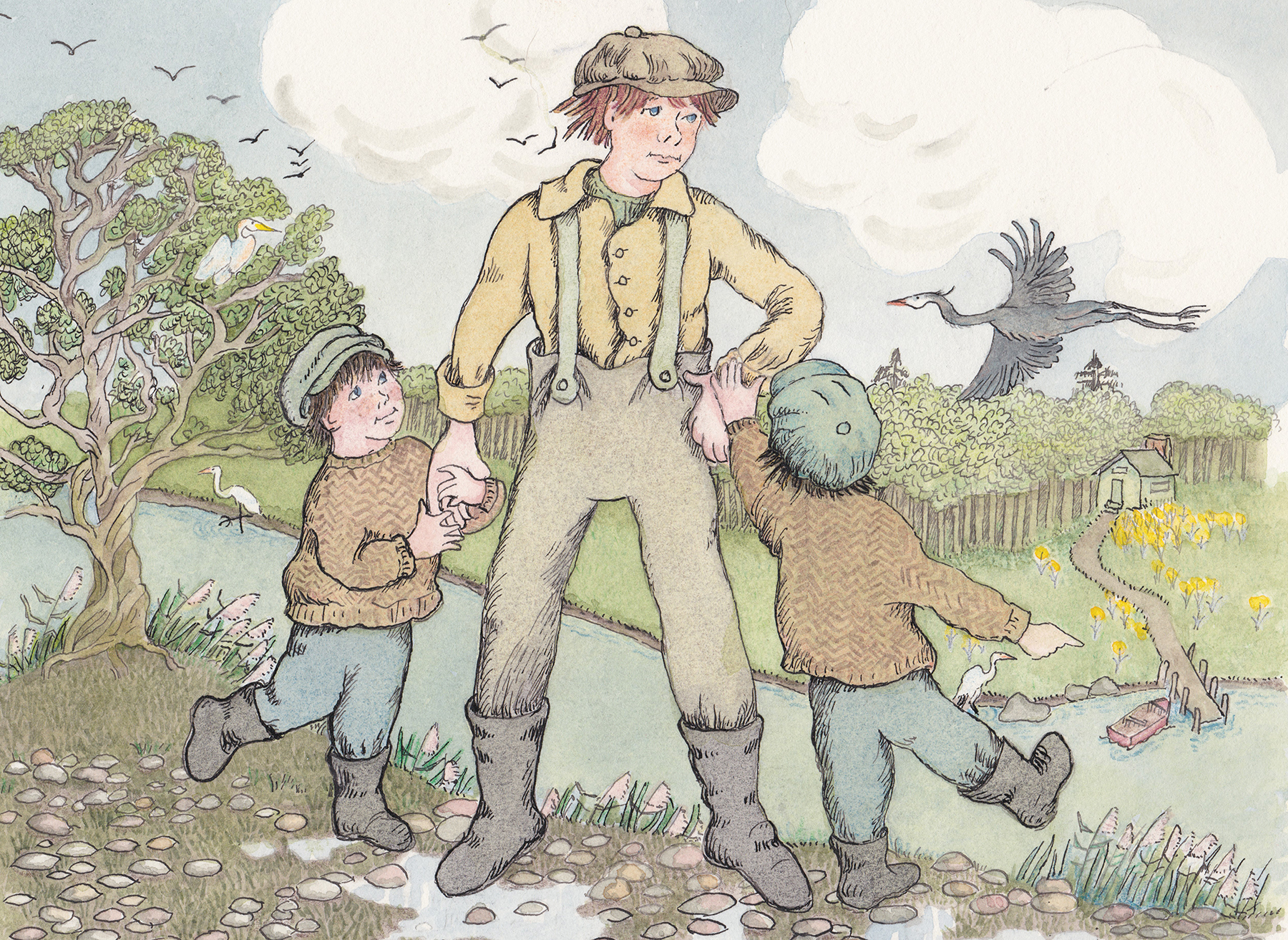

So, I go down the bank and pull the cart up to the road for them. “What’ve you got all wrapped up there, Clara?”

“Rescuing another bird, JJ, never saw the likes of this one.”

“It’s really sick,” Adam said. “It took all three of us just to wrestle it into the blanket stumbling all over the bank like it was; maybe got a broken wing.”

“Not a broken wing. Lame, that’s what it is,” Ben said.

These three pull their cart up and down the dock neighborhood like a tiny Greek chorus, seeking out and announcing tragedy and distress in the animal world. Ever since the day they found an injured seagull, took it home, wrapped it in a blanket, put it in a basket, and nursed it back to health, they marked their wagon with a red cross and made it their mission in life to save all birds in distress.

“He can’t walk, and he’s been plucked bald as a chicken,” Adam and Ben report as nearly in a single voice, “just one or two little black feathers with white dots left.”

“I’m pretty sure it was that new boy that done it,” Ben says.

“I think he’s mean, that one,” Adam adds. “If he’s the one what plucked him naked, it will be all his fault if this bird dies.”

“Like last Sunday,” Adam says, “when the preacher read part of that rhyme story about a man what killed a sea bird, and because it was such a mean thing to do, he had to tie the dead bird with a rope and hang it around his neck and wear it forever, so he’d never forget how evil his deed was.”

“Like last Sunday,” Adam says, “when the preacher read part of that rhyme story about a man what killed a sea bird, and because it was such a mean thing to do, he had to tie the dead bird with a rope and hang it around his neck and wear it forever, so he’d never forget how evil his deed was.”

“True is true,” Ben says. “That’s Bible truth; I heard the preacher say it.”

I laughed. “You two tadpoles telling me your sister’s got an albatross wrapped up in that blanket?”

“You think you’re so smart, JJ,” Adam says. “Well, we know how to fix him, just you watch. We’ll take him home and put some splints on his legs; they’re probably broken; we witnessed him; he can’t walk without falling over forwards.”

“The splints, that’s my job,” Clara says, hugging the bundle to her chest.

Judging by the size of the bundle, I decided it must be a goose. I unwrapped the blanket just enough to reveal a bald head and neck and one terrified red eye looking back at me.

“Oh spit! It’s a loon in molt,” I said, and quickly covered his head again.

“You have to put this poor bird back in the exact place where you found him. Where did you pick him up?”

“There.” Adam and Ben both pointed. “Past the outcrop we use to jump off of; by the swimming spot; where the mink lives between the big stones.”

I pulled the cart back down the grassy bank, Clara still clutching the loon, while the twins lead me to the scene of the rescue. As we walked, I told them about how when the loon molts, it loses every last feather on his body and can’t fly back to the lakes up north until it grows them all back. Then I told them how no loon can walk much on land because it’s legs are set all the way back by the tail feathers.

“Poor baby,” Clara says, stroking the blanket. “Did someone put you together all wrong?”

I watched as the three of them eased the featherless loon back into the water, just like I told them to, then they sat on the bank and watched to make sure he didn’t need any more help. As I walked away, I heard Clara say: “JJ knows so much about everything; it seems to me like there is always one more thing to learn about in life. I would have made some really fine splints, though.”

“Oh,” Adam says with a shrug, “he’s not so smart, just older.”

I catch up with Ray, who says, “What’d she have in that blanket?”

“A loon,” I say. “Funny, she was about to put splints on it. They thought its legs were broken because it couldn’t walk. They’re learning. Who knows, maybe they’ll be veterinarians when they grow up, all three of them.”

“And not work in the ferry business?” Ray said, smiling.

“Listen, Ray, we’re not all destined to work on the river.”

“Didn’t you decide a while back that you wanted to be a boat builder, JJ?”

“Yes, but I’d still be stuck here on the wharf; I’d like to see Boston, you know, other places, maybe New York. I could do all of that if I was a post rider.”

“But you don’t know how to ride a horse,” Ray says.

About the Author

Leslie Tryon is an award-winning author-illustrator of children’s books (Simon & Schuster publisher). Tryon has spent her life working in the arts. Her experiences include dancing on a cruise ship, working for the book review of the Los Angeles Times, choreographing theater productions, and creating books for children, earning her an ALA Notable award among many others.

Leslie Tryon is an award-winning author-illustrator of children’s books (Simon & Schuster publisher). Tryon has spent her life working in the arts. Her experiences include dancing on a cruise ship, working for the book review of the Los Angeles Times, choreographing theater productions, and creating books for children, earning her an ALA Notable award among many others.

Five generations of Tryon’s family served as ferrymen on the Connecticut River between Old Saybrook and Old Lyme, Connecticut, and many of those men were named JJ, which gave Tryon the perfect place to begin this series for Estuary.

Tryon lives in Westerly, Rhode Island, with her husband, JR Fowler; together they spend as much time as possible in their tandem kayak, along with their kayaking friends, tracing and exploring the coastlines of Rhode Island and Connecticut.