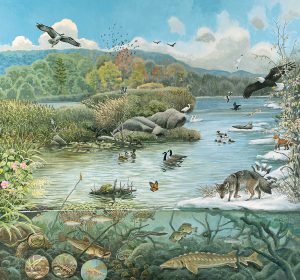

“Seasonal Ecology Mural” by Mike di Giorgio. Courtesy of Connecticut River Museum. Photo by Cultural Preservation Technologies.

In 2016, the Connecticut River Museum commissioned renowned wildlife artist Mike DiGiorgio to create a painting that would bring to life the tidal marshes of the lower Connecticut River. The painting was photographed by award-winning photographer Jody Dole and enlarged to a mural that is 81 ¼” L x 76” H and installed as a permanent exhibit at the Museum.

The goal of the mural project was to complete the important story of the ecological significance of the river, thereby enhancing school programming and visitor experiences, as well as increasing opportunities to foster environmental scholarship. The mural highlights the seasonality of the ecosystem from left to right, spring to winter. From top to bottom, the mural beautifully highlights the terrestrial landscapes of the forests in the background, the wetland transitional ecosystem, and the foreground aquatic ecosystem. The more commonly known native and invasive flora and fauna are accurately depicted in their ecosystems in the season they are blooming or most active. In spring, migratory birds have arrived on the river and it is common to see Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) hunting or preparing their nests, while the Swamp Rose Mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos L.) is blooming and the American Shad (Alosa sapidissima) is migrating to the streams that they were born in. In the summer months, insects such as the Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) and Wandering Glider (Pantala flavescens) are as active as the macroinvertebrates in the water and the frogs lingering on the water’s edge. As fall approaches, animals prepare to migrate south, such as the Tree Swallows (Tachycineta bicolor), and the deciduous trees prepare for dormancy but not before they give us a dazzling display of color. Winter on the river is a time when you can see into the forests and catch a glimpse of a coyote (Canis latrans) or red fox (Vulpes vulpes) or look up in amazement to see a Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) soaring on the wind. This mural captures the essence of the river ecosystem from living to nonliving organisms: the color of the water, the movement of the clouds, and the life cycle of the trees. There are more plants and animals that are well-camouflaged and not easily seen until further investigation. Not to be missed are the invasive species that pop-up in the water such as water chestnut (Trapa natans) and on land such as common reed (Phragmites australis).

The lower Connecticut River is a unique and special place. By bringing attention to the organisms that live and interact in this ecosystem, the Connecticut River Museum enriches both visitor and student understanding of the complex tidelands. Each niche can be further explored and understood in the interactions that make up the biodiversity of the Connecticut River. The mural assists in our appreciation of why we need to be stewards of the river, and how humans can impact the overall health of the Connecticut River.

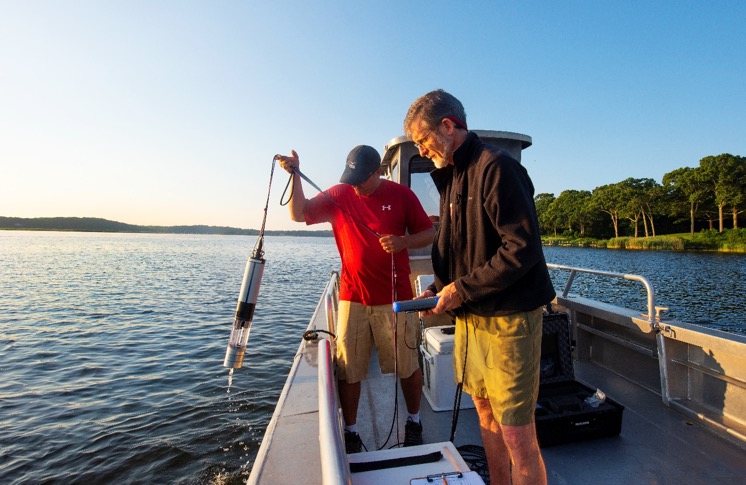

It’s All About the River’s Water Quality

Photograph by Jody Dole

"Clean, Healthy, and Full of Life! "

That’s Andy Fisk’s goal, and not just a dream, for the Connecticut River. Fisk, a patient, persistent, articulate scientist, is executive director of the Connecticut River Conservancy, a water-shed scale conservation organization based in Greenfield, Massachusetts. He can take water samples in the morning and debate experts on water quality policy in the afternoon. Fisk is among those who comprehend the arduous journey from water testing to legislation based on those tests, with a lag time of 5, 10 or even 15 years. Good, sound, effective water policy development must therefore necessarily survive multi-generations of elected officials in governors’ mansions as well as the White House.

A brief history of the environmental movement at the federal level bears repeating. Public opinion regarding air and water pollution was largely shaped by Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, published in 1962, and sensationalized catastrophes such as the 1969 fire on the Cuyahoga River in Ohio. In 1970, President Richard Nixon brought the Environmental Protection Agency into being with William Ruckleshaus as its first head. Ruckleshaus noted that, “public opinion remains absolutely essential for anything to be done onbehalf of the environment.”

The Clean Water Act of 1972 brought voluntary standards for discharges of pollutants into navigable inland waterways. President Jimmy Carter’s EPA administrator, Douglas M. Costle, who had also led the study in the late 1960s that recommended the creation of the EPA and in 1975 was Connecticut’s Commissioner of Environmental Protection, championed the Clean Water Act (as amended) of 1977. This act outlawed the use of any pipe or man-made ditch for discharges into navigable waters. The law also required industry to meet “best technological standards” for specified pollutants with a deadline for compliance of 1984. “Voluntary compliance” was replaced with “mandatory compliance with penalties.”

The die was cast. Industries, farms, and individuals made the necessary investments. The Connecticut River rose from a Class D (basically, dirty and unsanitary) River to a Class B River, which it is today. Fish and people were able to swim in their rivers once again. So, is the battle over? Is clean water here to stay? Not if one believed Ruckleshaus in 1972: “…the environment is a problem you must tend to everlastingly. It doesn’t go away. It’s not like putting out a fire or even building a highway. You can’t do it, then brush your hands and say, ‘On to the next task.’ You have to keep at it all the time; otherwise it starts to slide back.”

Sliding backwards may include acute problems such as bacteria caused by a leak or a broken pipe. Once detected today, however, such impairments are rectified and clean water is restored rather quickly.

The battle’s not over if you’re Andy Fisk, either. Fisk looks to the day when the Connecticut River is “clean, healthy, and full of life.” Just because it’s clean doesn’t mean it’s healthy, says Fisk. “Nevertheless, fish, wildlife, and plants will flourish in and along a healthy river. The goal is that decades from now, we could see the return of millions of blue-back herring, alewives, and shad.”

A river that is “clean, healthy, and full of life” would seem to be in everyone’s best interests. Fisk says work on “healthy” began 20 years ago involving matters such as storm water, nutrient control, and even the depth to which sunlight penetrates the water. The way forward is somewhat more complex, however.

The Clean Water Act has enabled the River to get to “clean” but falls short of helping to restore large populations of fish and desirable aquatic plant life. Now, says Fisk, the CWA must be married with various state wildlife conservation laws to get to “healthy.”

For the way forward, complex interdependencies become more important than simpler dependencies; dependencies such as, “the more dissolved oxygen in the water, the better it is for trout.” As an example of interdependencies, clearer water lets in more sunlight. Sunlight to greater depths allows more eelgrass to grow. Eelgrass is used by fish such as trout to spawn and is used by their young for protection. Therefore, more sunlight to greater depths is good for trout.

In addition, important balances must be maintained. Not all nutrients, nitrogen and phosphorous are bad, for example; they must be managed, however, to reach an optimum balance.

Technology is also a factor. If a subject can’t be measured far and wide and inexpensively then causal relationships cannot be substantiated and used in arguments for conservation policies. According to Fisk, relevant new technological developments will play an important role in showing the way to a river full of life.

Habitat and ecology issues also surface, with conservation advocates taking different positions on the same object in different regions. For example, the parasitic sea lampreys are viewed as undesirable in certain regions, but desirable in others, with both directions based on sound eco-logic. In Connecticut, for example, the state is aiding and abetting the growth of the lamprey population by stocking them upriver, and by providing access to their spawning sites above dams. As noted on the Connecticut River Conservancy website, “adult lampreys are an important source of nutrients for our rivers. After they’re born here in the Connecticut River, they head out into the oceans to live and grow. Once full grown, they migrate back to our rivers to spawn. After they lay their eggs, they all die. Their bodies become a food source for all sorts of other river life including aquatic insects, fish, and mammals. Lampreys support a vast food chain that keeps our rivers healthy and full of life.”

One gets the impression that the road to a clean and healthy River full of life will rely more upon persuasion than upon coercion. Andy Fisk seems primed for the task.

Prior to joining the Connecticut River Conservancy as Executive Director in 2011, Dr. Fisk served as Director of the Land and Water Quality Bureau at the Maine Department of Environmental Protection for seven years. As Maine’s land and water quality director, Fisk had extensive experience with a range of state and federal environmental quality statutes.

Dr. Fisk has a Ph.D. in Environmental Sciences, as well as a master’s degree in City and Regional Planning from Rutgers University. He has served as President of the Association of State and Interstate Water Pollution Control Agencies and Chair of the New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission (NEIWPCC). He has been active in land conservation for over a decade. At NEIWPCC, Fisk initiated the country’s first regional mercury clean-up plan for the seven Northeast states’ impaired waters, which maps out strategies to make the region’s fish safe to eat. Dr. Fisk is a member of Estuary magazine’s editorial advisory board.

A Treasured Refuge Becomes

Permanently Protected

By Bill Hobbs

Photography by Chris Zajac

People who enjoy the Fannie Stebbins Refuge can hike along its easy, wide trails and see a beautiful mosaic of pristine wetlands, ponds, meadows, and floodplain forest.

Alongside the Connecticut River, just a few miles south of Springfield, Massachusetts, is a 371-acre environmental success story, a jewel of a refuge, called the Fannie Stebbins Memorial Wildlife Refuge that will be a safe-haven for wildlife for generations to come.

This is a story about caring and tenacious residents and organizations, including a distinguished bird club, The Nature Conservancy, the town of Longmeadow, and two federal agencies. Together they forged innovative partnerships to raise money and manpower to reduce invasive plants on the refuge and reforest five old hay fields with 7,900 native tree seedlings, shrubs and ferns, creating the largest reforested floodplain on the Connecticut River.

After completing an extensive restoration project, The Nature Conservancy will transfer the Stebbins property to the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge, reaching their collective goal and safeguarding its future.

The 244-acre restoration area will be part of the US Fish & Wildlife-managed Conte Refuge’s four-state network of protected lands. These protected lands now total about 38,000 acres.

The Conte Refuge was created in 1997 to protect the entire watershed of the Connecticut River. Parts of the refuge extend into Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, including many creeks, streams, and tributaries.

People who enjoy the Fannie Stebbins Refuge can hike along its easy, wide trails and see a beautiful mosaic of pristine wetlands, ponds, meadows, and floodplain forest.

“It’s so peaceful, you really are immersed in nature,”

“It’s so peaceful, you really are immersed in nature,” said Cynthia Sommers, president of The Friends of Fannie Stebbins, an oversite group under the Conte refuge.

The Stebbins Refuge is home to nesting wood ducks, rare red-headed woodpeckers, numerous migrating birds, owls, hawks, an occasional bald eagle, including deer, coyote, bobcats, beaver, and river otters, to name a few species.

Enjoyed by hikers, birders, and photographers, alike, this newest addition to the Conte Refuge is the result of many caring women and men, who for over 70 years, endeavored to protect and preserve the property, and did.

One of the early champions of the Fannie Stebbins refuge was Kate Hale (formerly Kate Leary), a retired teacher and avid birder. “My love and appreciation for ‘Stebbins’ grew first from birding there with the Allen Bird Club, whose members began purchasing pieces of land and weaving them together in the early 1950s, to establish the Fannie Stebbins Memorial Wildlife Refuge,” Hale explained in an email.

The Allen Bird Club that Hale mentions is the oldest continually operating bird club in Massachusetts. It was co-founded by Fannie Stebbins, who the refuge was later named after, and Grace Johnson on January 8, 1912. Fannie Adelle Stebbins (1858–1949) was herself a colorful person. Not only was she the supervisor of Springfield’s Elementary School Sciences, but a respected birder.

The Allen Bird Club that Hale mentions is the oldest continually operating bird club in Massachusetts. It was co-founded by Fannie Stebbins, who the refuge was later named after, and Grace Johnson on January 8, 1912. Fannie Adelle Stebbins (1858–1949) was herself a colorful person. Not only was she the supervisor of Springfield’s Elementary School Sciences, but a respected birder.

In 1926, for example, Stebbins made the first regional sighting—rare then—of a glossy ibis. And in 1932, she recorded the second sighting in Massachusetts of a scissor-tailed flycatcher, a bird commonly found in Southwestern deserts.

After Stebbins passed, members of the Allen Bird Club named the refuge in her memory.

Hale, meanwhile, in the early 2000s, began to be concerned about the spread of invasive plants on the Stebbins property. She had taken classes from the New England Wildflower Society in Framingham, Massachusetts, and learned how native plants play a key role in blooming and attracting insects for migrating birds moving north in the spring, and fruiting for birds traveling south in autumn.

Hale, meanwhile, in the early 2000s, began to be concerned about the spread of invasive plants on the Stebbins property. She had taken classes from the New England Wildflower Society in Framingham, Massachusetts, and learned how native plants play a key role in blooming and attracting insects for migrating birds moving north in the spring, and fruiting for birds traveling south in autumn.

She also learned how exotic invasive plants, like Japanese knotweed, multiflora rose, bittersweet, barberry, and stiltweed can severely threaten native flora and fauna in preserves like Stebbins.

Hale made it her “personal mission” to put the Stebbins land under the care of a larger entity that would protect it in perpetuity.

In the spring of 2015, the Allen Bird Club formed a committee of five volunteers. They included Ray Burk, David Miller, Judy and Dudley Williams, and Hale. One of the first organizations they approached was The Nature Conservancy (TNC).

Markelle Smith, landscape partnership manager for TNC’s Massachusetts Chapter and Andrew French, project leader for the Conte Refuge, toured the refuge and liked it, setting negotiations and a two to three-year restoration plan in motion.

Important pieces to the success of the restoration included several actions from major organizations.

For example, AMTRAK, which had a rail line running through part of the refuge, agreed to install signal lights and gates at a crossing on the north end. The town of Longmeadow, which owns conservation lands abutting the Stebbins property, repaved one of the access roads, graveled in a trailhead entrance, and leased a small parcel of land to USFWS to allow them to build a raised platform, ADA accessible, for outdoor classrooms and public viewing of the wetlands.

"This is a positive model for future environmental projects.”

Steve Crane, Longmeadow’s town manager noted, “We wanted to make sure our amenity is a benefit to our residents, and it is with this refuge.”

Finally, The Nature Conservancy and US Fish & Wildlife Service devised a plan to reduce the number of invasive plants, strip five old hay fields down to bare earth and reseed them with 37 different species of trees, shrubs, and ferns.

David Sagan, a USFWS biologist, said, “In 15 years, we’ll get a canopy from these tree seedlings that’ll shade out the field tolerant invasive plants,” killing them.

Generous funding came from the Massachusetts office of the Natural Resources Conservation Service, a federal agency that provided funding for the project under its Agricultural Conservation Easement Program. They contributed nearly a quarter of a million dollars to purchase a permanent easement on the Stebbins property, ensuring the property would remain undeveloped, and $411,000 to fund the restoration.

When French was asked for his final assessment of the collaboration, he said, “There’s tremendous efficiency in partnerships, and invaluable relationships,” adding, “We

executed a strategy that anyone of us could not have done by ourselves.”

“This is a positive model for future environmental projects, and we want to do more of them,” French said.

Bill Hobbs is a nature columnist for The Day in New London, CT. For comments, he can be reached at whobbs246@gmail.com.

Post Cove, Deep River

Arrow-arum, water purslane, and false

pimpernel are new to me now

that I live on a riverine tidal marsh.

These plants grow about or in the cove

where, out with the tide and in,

the common mummichog and banded

killifish swim. I imagine if I’ve seen a thing—

golden club, sweet flag, reed canary grass—

its name will spring to mind when

I want it to, but the deep truth is I enjoy

the luscious touch of common names

about the roof and floor, teeth edge

of my mouth—the salivate, sexy sensation—

my way of kissing the ring of English

for having crowned me English-speaking.

One evening last summer I spied the marsh

bellflower—dabs of blue amid chartreuse-

bright wild rice sprigs—two yards from

bursts of bur-marigold and rosy meadow rue,

and I’m still hunting for the uncommon

Hudson arrowhead, the cut-leaved

water horehound. However did a plant get hound

in its name? But I don’t want a pause for

etymological dreaming to halt the susurrate

and rattling runs of consonants, the shallow

and broad bellow of vowels, all that music

that, in trickles or rills or dips or blows,

trips the switch of this or that synapse:

the Wernicke and Broca areas of my

cerebral cortex flaring up like hydrogen

firestorms on the sun, my entire body

scintillate and quick with the gush-in,

flush-out, whisking blood.

from The Banquet: New & Selected Poems

GRAY JACOBIK is a widely-published, nationally-recognized American poet. A sought-after reader and mentor, she is an emerita professor of literature, a literary critic and painter, and a deeply committed advocate for the literary and visual arts.

Gray has been honored with numerous prestigious awards, including the William Meredith Award for Poetry for a collection entitled The Banquet: New and Selected Poems, in which Name Gourmand appears. She lives with her husband, Bruce Gregory, in Deep River, Connecticut.

The Estuary’s Most [un]Wanted Plant is Under Water

Lily Pad? Guess Again.

It’s the Invasive Water Chestnut.

By Judy Preston

Photography by Jody Dole

The aquatic plant known as Trapa natans has the unfortunate common name of water chestnut, leading people who are first hearing about it to think that it may well be a bonus source of that good appetizer, with a strip of bacon wrapped around it.

The aquatic plant known as Trapa natans has the unfortunate common name of water chestnut, leading people who are first hearing about it to think that it may well be a bonus source of that good appetizer, with a strip of bacon wrapped around it.

But the reality is, this non-native species is an aggressive rooted aquatic plant with floating leaf rosettes and a central submerged cord that can extend up to 16 feet, enabling it to form a dense mat on the water’s surface. By July, plants produce a whorl of seeds (nuts) below the water’s surface that detach and sink once mature. Seeds have been shown to remain viable for up to twelve years, underscoring the threat of long-term establishment once this plant takes hold.

Hadlyme resident Humphrey Tyler surrounded by water chestnut plants removed by volunteers last summer from Connecticut River’s Selden Cove.

This invasive species has gradually been moving down the Connecticut River from several large concentrations in Massachusetts. In 2011, a baseline effort to locate, map, and remove occurrences in the Connecticut River estuary was funded by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, working with the Connecticut River Estuary Regional Planning Agency (subsequently RiverCOG) in Essex. Several large populations have been located in the estuary, including in Salmon Cove, Selden Cove, and even on the Connecticut River mainstem.

Early detection and control is essential to controlling Water Chestnut; extensive infestations in Lake Champlain in Vermont, and the Hudson River estuary in New York make it unlikely that complete eradication will be possible in those waters. Our estuary abounds with largely intact fresh, brackish, and saltwater tidal wetlands that are essential habitat for a concentration of resident and migratory bird and fish species. Water Chestnut has the potential to fundamentally alter the ability of the Connecticut River estuary ecosystem to continue to support the biological, economic, and social amenities that have been its hallmark.

Friends of Whalebone Cove President Diana Fiske, in blue kayak on right, helped organize more than 30 volunteers in kayaks, canoes, and motor boats...who spent more than 125 hours last summer pulling thousands of water chestnut plants out of Selden Cove.

In 2018, after the discovery of large concentrations of another aquatic invasive plant, Hydrilla, in the Connecticut River north of Middletown, an email list serve was formalized to help conservationists problem solve about how to protect the Connecticut River and its many coves and marshes. It will take the persistence, resources, and energy of many people to stem the tide of these plants in the estuary—and the entire watershed.

Hadlyme resident Joe Standart empties a bag of water chestnut plants removed by volunteers of the Hadlyme conservation group Friends of Whalebone Cove.

If you think you have found either of these plants, or are interested in helping join the effort to keep it out of the Connecticut River estuary, please contact Judy Preston ( judy.preston@uconn.edu), Margot Burns (mburns@rivercog.org), or Friends of Whalebone Cove (fowchadlyme@gmail.com).

Judy Preston works for the Long Island Sound Study and CT Sea Grant at UConn’s Avery Point campus in Groton. She lives in Old Saybrook.

One of 10 cartloads of water chestnut plants removed from Lyme’s Selden Cove last summer.

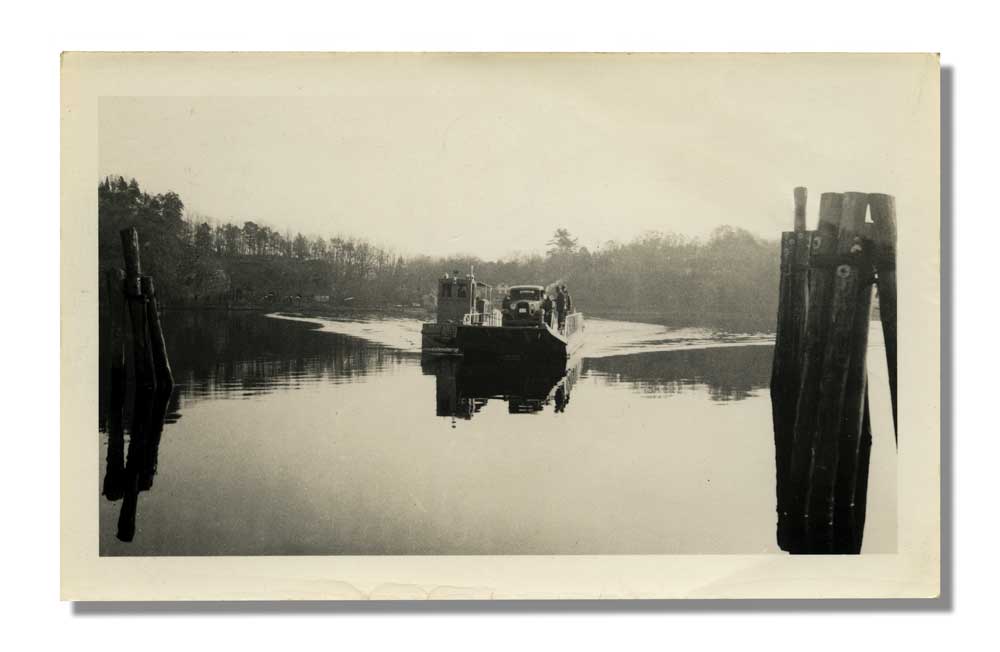

Ferries of the River

By Wick Griswold

Images courtesy of Connecticut River Museum

Hadlyme Chester Ferry, Fall 1933, Chester side

The Connecticut River connects us up and downstream. It also separates us from bank to bank. For thousands of years, indigenous people used dugout canoes to get from one shore to the other. The dugout could easily carry the people, meat, plants, tools, and fish around which their foraging lifestyle revolved. Trees transformed into boats were powered by paddle, wind, current, and tide. These organic craft were totally sustainable.

When English settlers arrived in the early 17th century, the canoe quickly became redundant. The colonist’s agricultural way of life required floating platforms to carry draught animals and wagons. Metal woodworking tools allowed the English Puritans to build scows to transport their livestock and gear across the River. These scows were the first ferries on the Connecticut.

When English settlers arrived in the early 17th century, the canoe quickly became redundant. The colonist’s agricultural way of life required floating platforms to carry draught animals and wagons. Metal woodworking tools allowed the English Puritans to build scows to transport their livestock and gear across the River. These scows were the first ferries on the Connecticut.

As early as 1638, the Colony of Connecticut regulated who could operate a ferry, where it was located, and how much ferrymen could charge for people, livestock, and carts. The family fortunate to get a ferry franchise became prominent citizens. They were first to get the news as travelers passed through. Ferryman often built inns and taverns at their slips to enhance their already steady income. Ferry rights were passed from generation to generation.

In 1655, a ferry was established between Rocky Hill and Glastonbury. Amazingly, that service continues in operation today! The ferry that connects Chester and Hadlyme came on line in 1769 and still chugs across the River. The original ferryman, Jonathan Warner, gave the operation to his son for a wedding present, with the stipulation that if it earned more than $30 per year the excess profit would revert to dad. Although there were once over 100 ferries on the Connecticut River, these are the only two that remain.

In 1655, a ferry was established between Rocky Hill and Glastonbury. Amazingly, that service continues in operation today! The ferry that connects Chester and Hadlyme came on line in 1769 and still chugs across the River. The original ferryman, Jonathan Warner, gave the operation to his son for a wedding present, with the stipulation that if it earned more than $30 per year the excess profit would revert to dad. Although there were once over 100 ferries on the Connecticut River, these are the only two that remain.

Bridges drove the ferries out of business. The boats were susceptible to ice, freshet, debris, and storms. Early wooden bridges could be swept away or burned. However, stone and steel began to span the River, and ferries were no longer necessary. When a bridge did wash away or burn, ferries were pressed back into temporary service until a new trestle could be cobbled together. Ferrymen fought against bridges in the legislature and town halls, but one by one, the charming boats were retired.

Until the early 19th century, ferries were powered by oars, sails, cables, poles, and horses. Steamboats were invented on the Connecticut River by John Fitch and Samuel Morey. Local ferries were quick to take advantage of this new energy source. Larger steamboats connected River towns to New York, Providence, and Boston. But the new technology could power land-based transportation as well. Soon, railroads were competing with steamers for passenger and freight business. Just as bridges were more reliable than ferries, trains were more dependable than steamboats.

Steamboat lines fought bitter political battles against railroad bridges across the River. They were able to block a train trestle from Old Saybrook to Old Lyme. That bascule, still in operation today, was not completed until 1907. Prior to that time, trains stopped at the River’s edge, uncoupled, slid their cars on to barges which navigated across the River and recoupled on the other side. It was a daunting exercise in engineering and logistics. Today, over 50 Amtrak and Shoreline East trains cross the 113-year-old truss every day.

The oldest continuous ferry service in the US in Rocky Hill-Glastonbury features a doughty, little tugboat, the Cumberland, which pushes the barge Hollister across the River from April to November. The rig can carry three cars, or four, if they are sub-subcompacts. Downstream in Chester-Hadlyme, the double-ended Selden lll can load up to nine cars. The trip affords splendid views of Gillette Castle, and can link with the Essex Steam Train for a nostalgic ride back into railroad history. Both ferries are run by the CT Department of Transportation. Every few years, frugal politicians agitate to end the ferry services. Waste of money, they say. So far, legions of ferry devotees have thwarted their efforts with phone calls, emails, rallies, meetings, torches, and pitchforks.

In June of 2019, the ferries and their fans exhaled a huge sigh of relief. The State of Connecticut allotted $4 million to refurbish the crumbling infrastructure at both landings. Deteriorating pilings will be replaced with wood from South American greenheart trees. It is the most rot-resistant wood in the world. This investment ensures that the ferries will continue to cross the River well into the foreseeable future. Come 2055, 400 years of continuous service between Rocky Hill and Glastonbury will be a commemoration truly worth celebrating.

Renwick (Wick) Griswold is a noted author and Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Hartford. His signature course is the Sociology of the Connecticut River. He is an associate producer of the documentary Ferry Boats of the Connecticut River. He also hosts Connecticut River Drift on iCRV Radio in Ivoryton, CT, and is Commodore of the Connecticut River Drifting Society.

Diatoms

On the hunt for what you can’t see in the Connecticut River

By Sally Warring

Scientific images by Sally Warring

Additional photography by Jody Dole

On a hot weekend in July, we headed out on the Connecticut River for a wildlife safari. We weren’t aiming to see osprey, swallows, bald eagles, or turtles, though we saw plenty of those. Instead, we were on the hunt for the River’s smallest inhabitants… its microbial wildlife. The presence of such wildlife can be an indicator of the health of a river.

On a hot weekend in July, we headed out on the Connecticut River for a wildlife safari. We weren’t aiming to see osprey, swallows, bald eagles, or turtles, though we saw plenty of those. Instead, we were on the hunt for the River’s smallest inhabitants… its microbial wildlife. The presence of such wildlife can be an indicator of the health of a river.

For a microbial safari one needs only a receptacle to hold a water sample, a pipette for transporting a small amount of the water sample onto a glass microscope slide, a glass coverslip to hold it in place and, of course, a microscope.

Microbial wildlife thrive all around us. These organisms are tiny, single-celled creatures that lead complex lives and play important roles in our ecosystems. Most are no more than one tenth of a millimeter long, well below the threshold for visibility by the human eye. With a microscope, we can magnify these creatures one hundred, two hundred, or even four hundred times to observe their forms and behavior.

When hunting for microbes there are some signs visible to the naked eye: when microbes grow to large populations, their “communities” can become visible. On our River trip, we were on the lookout for signs of such microbial communities.

Color is an important sign. Microbes come in greens, browns, reds, yellows, and whites, and when you see water or a surface that has taken on one of these hues, chances are you’re looking at a microbial ecosystem.

Once on the River, we scooped up some water that was covered in a whitish foam and streaked with brown. Foam is another sign of microscopic lifeforms. Foam is produced when the movement of the water churns up organic matter, mostly proteins and fats, from suspended microbial organisms. Sure enough, once we got this foamy water under the microscope, we found the cause of these visual aquatic phenomena: Diatoms.

Once on the River, we scooped up some water that was covered in a whitish foam and streaked with brown. Foam is another sign of microscopic lifeforms. Foam is produced when the movement of the water churns up organic matter, mostly proteins and fats, from suspended microbial organisms. Sure enough, once we got this foamy water under the microscope, we found the cause of these visual aquatic phenomena: Diatoms.

Diatoms are beautiful single-celled microbial algae. They are common in freshwater, saltwater, and everywhere in between. All algae diatoms live off sunlight. Inside each cell is a golden-brown chloroplast, the same ingredient that converts sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into food for plants. The diatoms float in the upper strata of water where light is plentiful, making sugars from light energy. This produces much needed oxygen; world-wide it is estimated that diatoms provide 20 percent of global oxygen.

Diatoms are expert builders. Each diatom absorbs silica from the environment, then extrudes that silica to create a shell around its soft single-cell body. These glass shells are called frustules. Many are intricately shaped and beautifully decorated. Some shapes help with flotation and movement, while other features allow for the exchange of gasses and material between the cell and its surroundings.

Some diatoms move by excreting a kind of mucus out of a groove called a raphe; the cell uses this mucus to slide over surfaces. You can find surface-dwelling diatoms all through the River. The next time you see a submerged plant, look to see if it’s coated with a brown or soil-like layer; that layer is probably from diatoms that have attached to the submerged plant.

Diatoms sit at the base of the food chain providing meals for other microbes and zooplankton. When a diatom dies or gets eaten, the tiny silica frustule remains and falls to the sediment layer, slowly building up over time. Under the right conditions that sediment layer can harden and fossilize into a useful sedimentary rock known as diatomite or diatomaceous earth.

In the pictures here, the diatoms with golden-brown colors are living; the ghostly clear shapes are the empty frustules. Each differently-shaped diatom or frustule represents a different species of diatom. There are around 12,000 diatom species currently described and probably many more to discover. As we observed, many diatom species call the Connecticut River home.

Diatoms are beautiful single-celled microbial algae

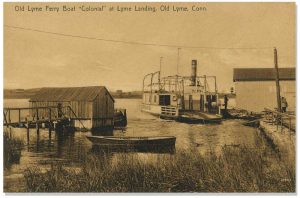

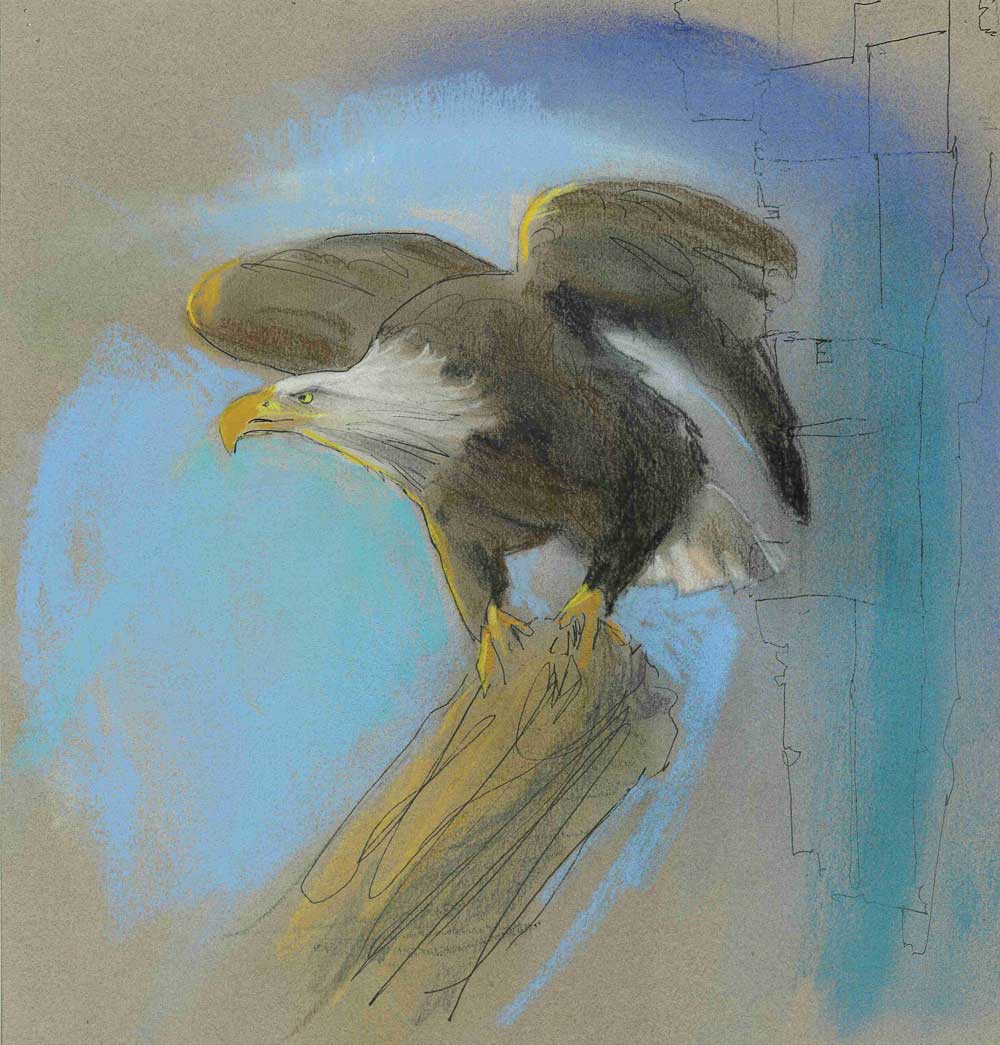

Bald Eagles of the Connecticut River

A Status Report on the Bald Eagle in the Connecticut River Watershed

By John Buck

photograph by Frank Dinardi

sketch by Bruce Macdonald

Dead drifting my canoe along a stretch of the upper Connecticut River a few miles upstream of the Wilder Dam, a flash of white against the dark green pine background revealed the perching spot of an adult Bald Eagle. I had been receiving credible reports of a pair of eagles in the area and wanted to see if I could confirm a nest or at least a territorial pair. Remaining motionless for fear of flushing the bird, I waited in hopes it might reveal a second adult or even a nest. Eagle nests are unusually difficult to spot by themselves, despite measuring as much as six feet in diameter and weighing several hundred pounds.

Dead drifting my canoe along a stretch of the upper Connecticut River a few miles upstream of the Wilder Dam, a flash of white against the dark green pine background revealed the perching spot of an adult Bald Eagle. I had been receiving credible reports of a pair of eagles in the area and wanted to see if I could confirm a nest or at least a territorial pair. Remaining motionless for fear of flushing the bird, I waited in hopes it might reveal a second adult or even a nest. Eagle nests are unusually difficult to spot by themselves, despite measuring as much as six feet in diameter and weighing several hundred pounds.

The upstream breeze counteracted the River’s current allowing me to remain in place for nearly an hour. A second bird never appeared and whether the eagle decided I wasn’t worth the risk of remaining, or it was hungry, or simply wanted to see more of the River, it flew off to the north. With a mighty push of its legs, shaking the pine bough as it released its grip, and a few deep powerful strokes of its six-foot wingspan, the eagle was soon out of sight. Though I had seen many eagles over the years, my feelings of awe and inspiration were just as profound as my first encounter so many years ago. It is no wonder the peoples of the Wampanoag, Pequot, Abenaki, and Quinnipiac, were among the many first Nations to revere the Bald Eagle and place them highly within their tribal rituals and customs.

Ever since the Continental Congress officially adopted the eagle in 1782 as our nation’s national symbol, the species has had a remarkably difficult existence during the past 200 years. Habitat loss due to extensive land clearing and polluted waterways, popular fashion using wild bird feathers, persecution, and later, the introduction of DDT into the food chain resulted in an estimated population of less than 500 nesting pairs in the lower 48 states by the 1960s. And, no nesting pairs were found in the Connecticut River basin as recently as 30 years ago. In fact all of New England was void of nesting Bald Eagles except for some of the coastal and more remote habitats of Maine.

Through public awareness and laws,

habitat quality steadily improved to the

point where eagles could find suitable

nesting and feeding habitat.

Today’s eagle population is a different story. There are an estimated 10,000 nesting pairs in the 48 lower states including at least 50 pairs in the Connecticut River basin. Through public awareness and laws such as the Migratory Bird Treaty ACT (1918), the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (1940), the Clean Waters Act (1972), and the Endangered Species Act (1973), habitat quality steadily improved to the point where eagles could find suitable nesting and feeding habitat. These actions and the banning of DDT in 1972 allowed for the growth and resurgence of Bald Eagles throughout the land. So well has the eagle population recovered that it was removed from the federal endangered species list in 2007. This success story is being repeated in the Connecticut River Basin, too.

The lower part of the River was first to experience the eagle’s return. First to have eagles disappear from the state, Massachusetts last recorded nesting eagles in Sandwich in 1905. But from 1982 to 1988 the state undertook an aggressive effort to reestablish a nesting population by importing orphaned eagle chicks from the Great Lakes region of Michigan and neighboring Canada. The transplanting work centered on the Quabbin Reservoir where, during the six-year reintroduction, 41 eaglets were raised to adulthood, and by 1988, Massachusetts had their first nesting eagles in 83 years. Success at Quabbin extended beyond its borders to include 11 pairs along the Connecticut River by 2018. Eagles are a regular sight along the River in Massachusetts. Turner’s Falls (Greenfield) and vicinity has proved popular for nesting eagles. So well have the eagles faired in Massachusetts that the state has proposed the species be down-listed from threatened to a species of special concern.

Farther downstream, Bald Eagles have experienced similar success. Sharing the story of the eagle’s perilous decline with the other Connecticut River states, Connecticut was fortunate to retain a modest residual population of wintering eagles along its lengthy Long Island coastline, especially at the mouths of major rivers like the Connecticut. But, in 1992, a pair of eagles successfully reared two chicks in Litchfield County. Since then the state’s eagle population has steadily grown to where the state downlisted the eagle population from endangered to threatened in 2010. Connecticut’s eagle population continues to expand and by 2018, state biologists estimated between 50–55 pairs to be residing in the state. Although winter continues to be the best time to view eagles in towns such Haddam and Essex, tributaries of the Connecticut like the Scantic River in Sommersville and Shenipsit Lake in Ellington also support a feeding habitat and potential nesting territories as well as offer viewing opportunities.

Getty Images, Mariusz Stanosz

Vermont and New Hampshire have shared a long and interesting history together. Beginning with the fact that, while New Hampshire was one of the original 13 colonies to form the United States, Vermont (once named New Connecticut) remained as an independent nation from 1777 until 1791 when it was admitted to the union as the 14th state. That subtle but important difference is still played out in many things today including Bald Eagle restoration. The difference is due to the fact that 90 percent of the River between the two states belongs to New Hampshire. The eagles, however, don’t know that, nor do they care. Eagles on both sides of the River hunt the River’s tributaries in both states. The only boundary lines they are concerned with are those established by the eagles themselves. Like so much of the habitat in Massachusetts and Connecticut, reforestation along the upper reaches of the River is, once again, an excellent eagle habitat.

New Hampshire reported its first successful nest in 1988 in the Umbagog National Wildlife Refuge. Though not part of the Connecticut River drainage, the first eagle nest is always significant. As New Hampshire’s eagle population steadily grew other major water bodies began to attract the expanding population including the Connecticut River. From Hinsdale on the Massachusetts line to Northumberland in Coos County, near the Quebec border, eagles have taken advantage of the hundreds miles of unoccupied habitat. New Hampshire officials report over 50 nesting pairs in the state today with nearly a dozen calling the Connecticut River their home.

Vermont, on the other hand, despite its abundant unoccupied habitat, is one of the last states in the lower 48 to have a nesting pair of Bald Eagles. For reasons known only to the eagles, Vermont’s first modern day nesting pair was discovered in Springfield in 2002. As is often the case with new nesting pairs, success often requires more than one season’s attempt. However, nesting success finally occurred with another pair farther upstream in the town of Concord in 2008, and the Springfield pair was eventually successful. With that, Vermont ended a 60-year absence of the species from the state. As with the other three Connecticut River watershed states, Vermont’s repopulation progressed in fits and starts. Today, record numbers of eagle nests and offspring are being reported each year centered on the state’s three major eagle waterbodies (including Lake Champlain and Lake Memphremagog). Vermont wildlife officials report over 30 nesting pairs in the state with nearly a third of them lining the western shore of the River. However, without those first nests along the Connecticut River, the Bald Eagle’s resurgence would have been delayed even further.

A mere 50 years ago there were an estimated 450 nesting pairs of Bald Eagles in the entire continental United States. Today there are that many in New England alone. Whether by human assisted transplant efforts or through natural expansion of populations along the coast of Maine and Long Island Sound, it is clear the Connecticut River has served as a vital destination for Bald Eagle recovery. With continued habitat protection efforts, vigilance towards environmental toxins, and preventing dilution of important legal protections (e.g. Migratory Bird Treaty Act), the upper limits of Bald Eagle occupation in the basin are yet to be seen. There is still much unoccupied habitat within the River basin. Although Bald Eagles are normally quite wary of people, some have shown more tolerance than others and will likely continue to expand in Connecticut and Massachusetts. With so much unclaimed habitat in New Hampshire and Vermont yet to be spoken for, the future for this magnificent species looks very bright along the 410 miles of the Connecticut River.

JOHN BUCK is a fifth generation Vermonter. John’s interest in the natural world was shaped during his early years in rural Orange County at a time when there were more cows than people.

John received his BS and MS degrees in Wildlife Biology at University of Vermont. Following graduation, John was hired by the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department as a founding staff member of the Department’s new wildlife habitat management program for private and public lands. Throughout his 39-year career, John managed habitat conservation projects. Until his recent retirement, John focused on threatened and endangered species and conservation of their respective habitats.

In his new career, along with his family, John runs a small organic bird-friendly maple syrup operation in Washington, Vermont. When not working the woods, John sings in the baritone section with the Burlington-based choral group Solaris Vocal Ensemble and with the Vermont Symphony Chorus.

American folklore has it that Benjamin Franklin suggested to the Continental Congress that the Wild Turkey be selected for the national symbol instead of the Bald Eagle. While that suggestion cannot be substantiated, he did offer in a 1784 letter to his daughter that the turkey is a far more respectable bird as indicated by its cunning and bravery. Franklin went on to describe the eagle as having a “low moral character” for its reputation as a thief and a bully. Though the turkey is all of what Benjamin Franklin described it as, I turned my canoe for the Vermont shore thinking how different history might have been had the Founders chosen anything but the Bald Eagle.

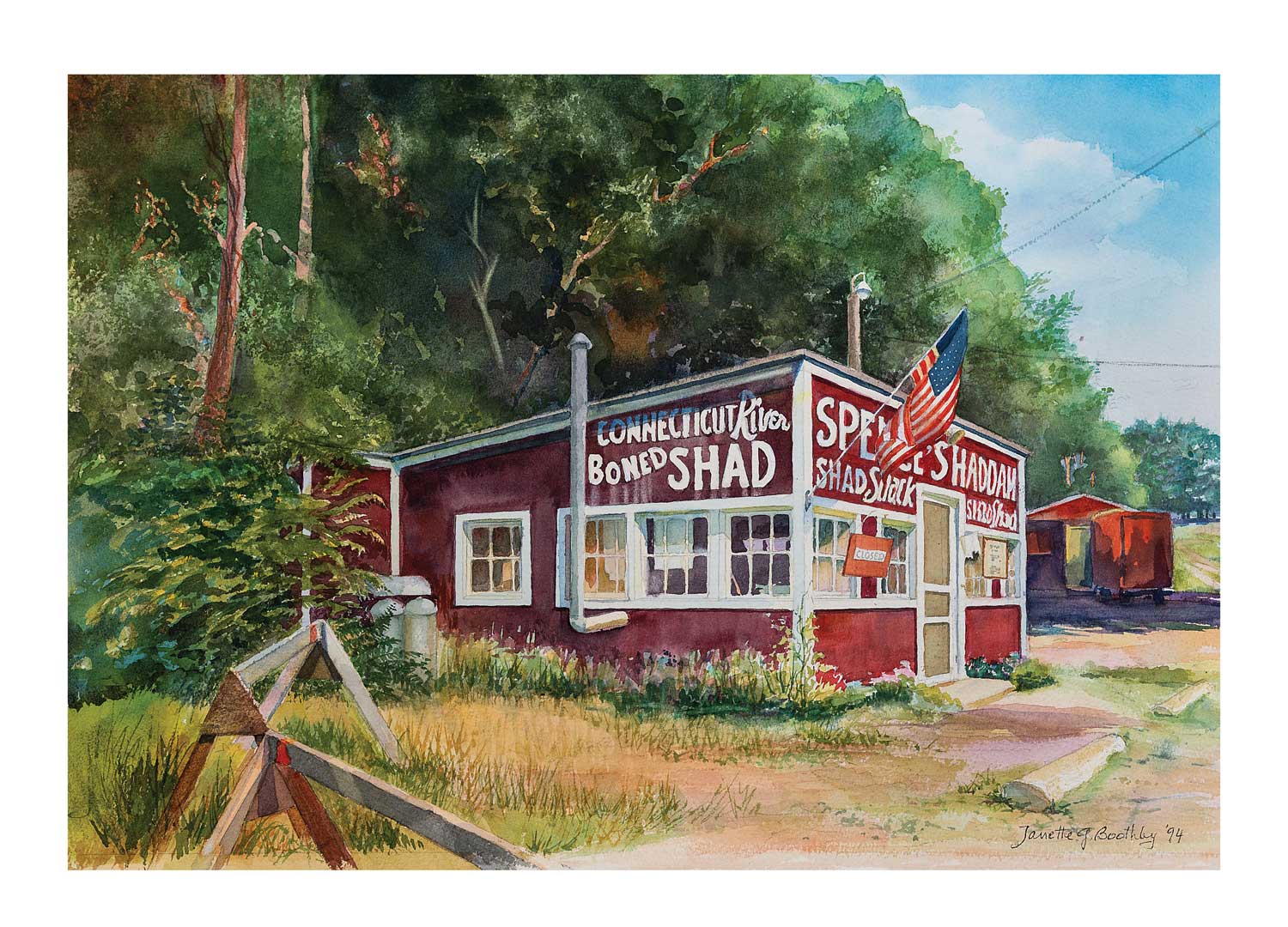

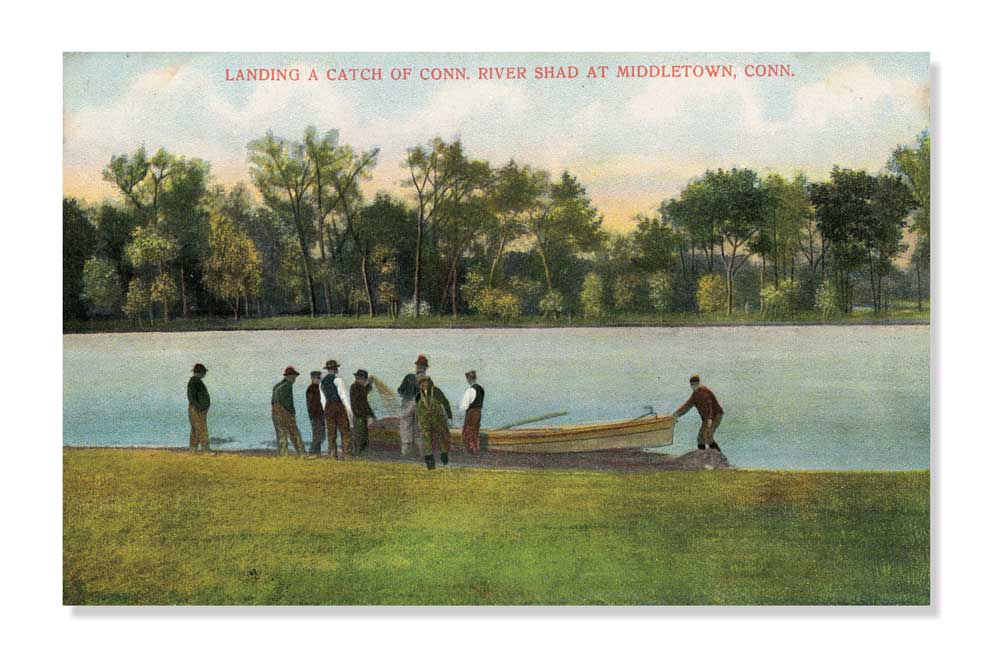

The Shad Spirit

By Erik Hesselberg

Artwork and objects courtesy of the Connecticut River Museum. Shad Shack painting by Janette Boothby. Photography by Jody Dole. Shad Drawing from Getty Images, gyro

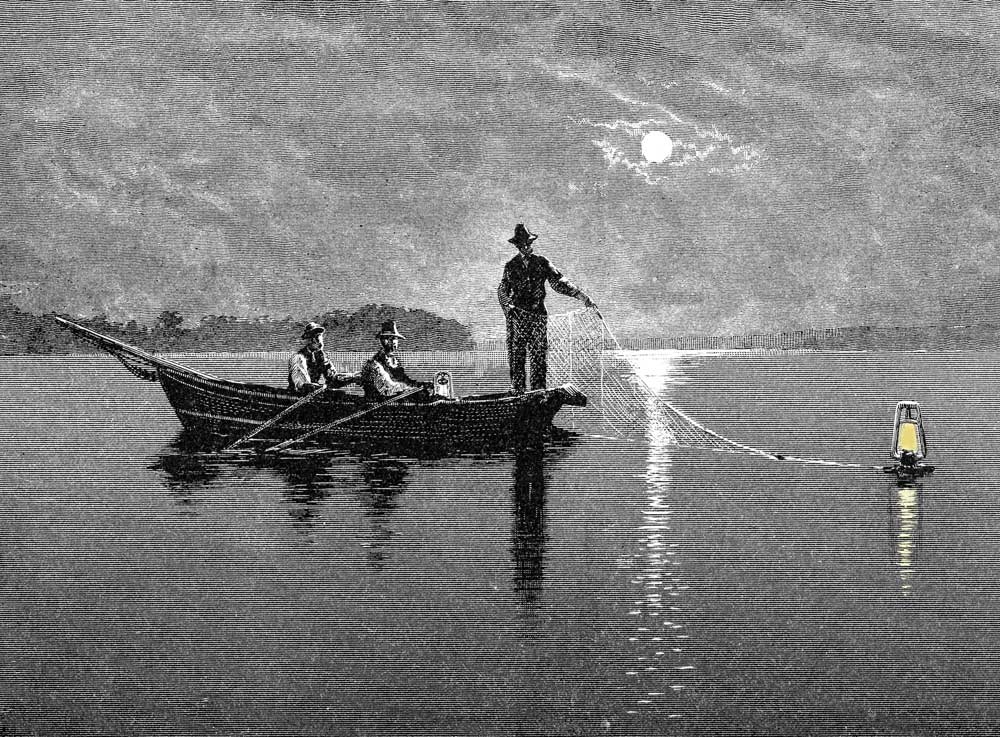

On a fly by day or a gill net by night, when the shad run, we fish!

Early on an April morning, a cold mist lies over the Connecticut River. When the sun breaks through and the mist rises, there is shimmering on the water. Regularly, for a brief moment, the modern melds into the timeless and across the expanse of marshes and blue water you see the silver flash and hear the blare of a diesel horn from the Old Lyme Draw every time an Amtrak train speeds along the old truss railroad bridge. You imagine some of the busy commuters on their way between Boston and New York looking up from their laptops to refresh themselves with a view of the tidal creeks and coves and the wide River meeting the waters of Long Island Sound beyond. The sleeping yachts are still wrapped in their white plastic cocoons for the winter. Marking the shore in the distance stands Lynde Point Lighthouse, and beyond, Saybrook Outer Light.

The brackish water of the wide estuary is warming past 40 degrees Fahrenheit. In front yards, yellow forsythia has appeared, and clusters of yellow daffodils push up. The season has begun, and the shad are running. Where marsh becomes damp woods, you can still see here and there among the bare branches the fresh white blossoms of a small tree above the fiddlehead ferns and green shoots of skunk cabbage. This is a species of Amelanchier, the shadbush, given this homely name by the early English settlers because it flowers about the same time huge schools of shad return from the ocean and swim up New England tidal rivers.

The brackish water of the wide estuary is warming past 40 degrees Fahrenheit. In front yards, yellow forsythia has appeared, and clusters of yellow daffodils push up. The season has begun, and the shad are running. Where marsh becomes damp woods, you can still see here and there among the bare branches the fresh white blossoms of a small tree above the fiddlehead ferns and green shoots of skunk cabbage. This is a species of Amelanchier, the shadbush, given this homely name by the early English settlers because it flowers about the same time huge schools of shad return from the ocean and swim up New England tidal rivers.

A dirt road full of potholes leads down by an abandoned power station to an old stone wharf with weathered wooded slips along one side. Pow erboats are predominant, but once at Ferry Dock, as this wharf is known, you see the remnants of a fishing fleet—a 40-foot trawler, a few lobster boats, and several flat-bottomed, open skiffs about 20 feet long. Back from the water among the fishermen’s cottages is Ted’s Bait Shop, owned by Ted Lemelin, who used to take one of the long skiffs out at night to set his drift nets for the spring shad fishing. Ted is a hard guy to know, but one night in May, he agreed to take me out fishing with him.

erboats are predominant, but once at Ferry Dock, as this wharf is known, you see the remnants of a fishing fleet—a 40-foot trawler, a few lobster boats, and several flat-bottomed, open skiffs about 20 feet long. Back from the water among the fishermen’s cottages is Ted’s Bait Shop, owned by Ted Lemelin, who used to take one of the long skiffs out at night to set his drift nets for the spring shad fishing. Ted is a hard guy to know, but one night in May, he agreed to take me out fishing with him.

There has been shad fishing on the Connecticut River—more or less this kind of laying out of carefully arrange weirs or barriers—for thousands of years. River Indians called the first full moon in March the Shad Moon. (Today, on the Connecticut River shad season runs from April 1 to June 15.) Taking his cue from Native belief, Connecticut poet John G.C. Brainard in 1824 wrote “The Shad Spirit,” telling of a spirit guide in the form of a great bird who appeared in early spring to lead the fish schools up the coast to the mouth of the Connecticut River:

To fair Connecticut’s northernmost source,

O’er sand-bars rapids and falls,

The Shad Spirit holds its onward course,

With the flocks with his whistle calls.

The broad estuary between Saybrook and Old Lyme bristled with fishing piers. From the piers haul-seining crews worked nets a quarter mile long. A thousand or even two thousand fish in a single sweep of the net was not uncommon. Shad was so plentiful it was used as fertilizer or shipped to the slave-worked sugar plantations of the Caribbean. However, with the steamboat the fresh catch could be packed on ice and sent overnight to New York and Boston. The humble fish began to rise in estimation, and soon Connecticut River shad and shad roe graced the tables of flossy restaurants like New York’s Delmonico’s.

A planked shad dinner is still a seasonal treat, although the market for the fish has dwindled, as an older generation raised with shad bakes and the like slowly disappears. Today, only a handful of boats go out at night to lay drift nets for shad, classified as an “artisanal fishery” fading into folklore. In 10 years, the gillnet shad fishery will have likely disappeared altogether. “It’s hard work and you fish at night, so you’re going without sleep for the five- or six-week season,” a fisheries biologist told me. “The gear hasn’t changed in 100 years. Only a few diehards do it now.”

Some years ago at Ferry Dock, I met Reginald “Butch” Rutty, a commercial fisherman for 40 years. Rutty talked about the days when 20 boats raced out to the Railroad Bridge at night during shad season to be the first on the fishing grounds. The bridge marked the top of the “reach,” the territories of water allotted to fishermen over generations to lay their nets. “The first boat on berth earned the right to the first drift,” Rutty said. “You’d anchor your boat on the south side of the bridge to establish your spot. Some guys got out there early, which was O.K. as long you left your net in the boat.”

Some years ago at Ferry Dock, I met Reginald “Butch” Rutty, a commercial fisherman for 40 years. Rutty talked about the days when 20 boats raced out to the Railroad Bridge at night during shad season to be the first on the fishing grounds. The bridge marked the top of the “reach,” the territories of water allotted to fishermen over generations to lay their nets. “The first boat on berth earned the right to the first drift,” Rutty said. “You’d anchor your boat on the south side of the bridge to establish your spot. Some guys got out there early, which was O.K. as long you left your net in the boat.”

Rutty got his start fishing with Kenny Swain, a hardnosed commercial fisherman out of Old Saybrook who described his line of work as “a tough racket.” Rutty signed on as Swain’s “striker,” or junior partner, but a few weeks in, may have questioned the decision when their 35-foot fishing boat was broadsided by a 54-foot cabin cruiser, nearly slicing it in two. Swain and Rutty were thrown into the water but were plucked up by a passing vessel. Both were bruised and battered but refused medical attention and were back fishing the next day.

Kenny Swain fished right to the end. They still talk about the bitter cold January morning in 1980, when Swain collapsed on his boat on Long Island Sound. A passing boat spotted the distressed vessel, but it was too late. Swain’s death was a blow to the tight-knit Old Saybrook fishing community, especially Lemelin, who also got his start fishing with Swain. Indeed, much of what he knew about shad, he said he learned from Swain.

There was fog in the evening. The next day, Ted called to say the weather would be clear and he was fishing that night if I wanted to tag along. It was long after midnight when we pushed off from the dock and headed out into the blackness of the Connecticut River. John Rogers, Ted’s fishing partner, was in the bow. Approaching a red buoy, Ted cut the motor. With his free hand he directed a floodlight onto the downstream side of the buoy—No. 14, marking the eastern edge of the dredged channel. Shad gill-netters typically fish an ebbtide, letting the net drift down with the current a mile or so before taking it up. You don’t want it to move too fast. “I don’t know, Johnny,” he said to Rogers. “The current’s still running pretty good.” When shad, a schooling ocean fish, come into the River to spawn, they follow the deep channels. Approximately half a million fish would head upriver that year, which meant a half million fish would pass Red Buoy No. 14. Ted would be happy to intercept 150 of these fish, but his success tonight seemed to depend on how well he read the eddy coming off the buoy. “I don’t want the current to take my net down too fast and get all hung up in South Cove,” Ted said. “It’s kind of a crap shoot.”

Leaning on the throttle, Ted cruised upriver to a spot just south of the railroad bridge where he would make his set. He and John wear the uniform of commercial fishermen everywhere—flame-orange, rubberized bib overalls and wool caps. They are heavily bearded. Working in tandem, they began paying out 1,500 feet of net across the channel in a long, lazy arc. Shad have a remarkable ability to detect and avoid nets. But they can’t see them at night. Swimming into the nylon monofilament, the fish are caught at the gills.

These gill nets have 5 1/2-inch meshes which select for the coveted female roe shad. (Males are called bucks.) Ted’s net is 15 feet deep, about the depth of the channel, held down in the water by metal rings and buoyed by plastic floats, still called “corks” from the old days. The rings tear off if the net gets hung up on the bottom. Battery operated lights mark the ends, a rare concession to modern technology. One is blue, blinking—a signal to other boaters to stay clear. Ted and John would let the net drift down with the current about a mile before taking it up, just above South Cove. If they’re lucky, they would catch some fish.

Between us and the bridge we saw the lights of a fishing boat. “That’s Gary,” Ted said, referring to Gary Rutty, Butch Rutty’s brother. Amos Swain and his crew were also out tonight. Ted shook his head. “Three boats! Hell, I remember when you had to fight for your spot there were so many shad boats on the water. One guy would set, then another and another right on down the line. If you didn’t set in time, you’d lose your spot. There were fistfights back at the dock.”

Originally from Bath, Maine, Ted came to Old Saybrook in the 1970s. Shad fishing was booming. “I had 12 people working for me,” he said. “Sometimes, we boned 1,000 fish a day. Dock & Dine was buying 200 pounds of fish a week. It was good money. You could clear $5,000 even $10,000, in just five or six weeks. Today, kids don’t even know what a shad is. All my customers are old. When they come to pick up their fish, I’ve got to bring it over to them because they can’t walk.”

Originally from Bath, Maine, Ted came to Old Saybrook in the 1970s. Shad fishing was booming. “I had 12 people working for me,” he said. “Sometimes, we boned 1,000 fish a day. Dock & Dine was buying 200 pounds of fish a week. It was good money. You could clear $5,000 even $10,000, in just five or six weeks. Today, kids don’t even know what a shad is. All my customers are old. When they come to pick up their fish, I’ve got to bring it over to them because they can’t walk.”

At 3 a.m. on the Connecticut River, the air is cool, damp, and salty-tanged. Mist rises from black, glassy water. The long, low silhouette of Great Island stretches away to Long Island Sound. Off in the distance, Lynde Point Light winks on, then off. Ted shined his floodlight along the length of his net. It was lying diagonally across the channel.

“She’s sagging and I ain’t bragging,” Rogers said, referring to the belly in the —not an encouraging sign. “We’ll be lucky if we catch 10 fish,” Ted grumbled.

“She’s sagging and I ain’t bragging,” Rogers said, referring to the belly in the —not an encouraging sign. “We’ll be lucky if we catch 10 fish,” Ted grumbled.

The two fishermen start hauling. The first 50 feet contain only stripers, the bane of the shad fishermen, as they eat shad. They also foul your nets. Commercial striped bass fishing is banned, so this bycatch goes over the side. Finally, a shad. Then two, three. Ensnared in the net, the fish barely twitch. Ted and John extract the gilled fish by gripping them tightly between their knees and forcing their heads through the tight meshes. The shad are tossed into a plastic tub in the stern. More net, more shad. The tub is filling up. By the time all 1,500 feet of net is in the boat, 40 shad lie in the tub, their big silvery scales shimmering under glaring lights.

Ted would go broke if he had to rely just on shad fishing for his income. His real work is running his bait shop and a car-towing business. Ted was discouraged when his son didn’t want to carry on the tradition. “The other day I asked him what wanted to do when he was older,” Ted said. “You know what he said? ‘Dad, I can tell you what I’m not going to do. I’m not going to be a fisherman.’”

Two hours on the River and all Ted has to show for it is 40 fish. Still, there are other compensations. Few places are as peaceful as the Connecticut this May night. At 3 a.m., Ted and John own the River. Looking down at hiscatch, Ted says, “I don’t know John. It ain’t great. But it ain’t bad. I think we’ll make another drift.”

Erik Hesselberg has been writing about the Connecticut River for twenty years, first as an environmental reporter for the Middletown Press, and then as executive editor of Shore Line Newspapers in Guilford, where he oversaw twenty newspapers. He lives in Haddam, Connecticut, where he is at work on a book about Connecticut River steamboats. A portion of this story previously appeared in the New Haven Register in a slightly different form.

In Awe of the Osprey

By Eleanor Robinson

Image Credit: Kris Rowe

During the month of March, the onset of spring in New England is revealed by the arrival of a conspicuous coastal and estuarine raptor—the Osprey. It may be blowing hard on Connecticut salt marshes with temperatures hovering in the 40s, but for Osprey, this time is ripe for reproduction.

Just when winter is feeling too long, and cooped up New Englanders are suffering from weather-induced grouchiness, this magnificent flyer returns from South America to dazzle us. The return of the Osprey and everything about the subsequent nesting season is “bird TV.” Ospreys put on a show on the sometimes snowy March shoreline as we await the release of the brutal grip of winter.

If you are fortunate enough to care for a child or a grandchild, the possibility of a late March Osprey sighting is an excuse for a foray outdoors, to observe the shift in seasons and to witness the wonder of nature. Ospreys can be helpful as nature’s gateway bird to some 2nd or 3rd generational fun outside. Ospreys are low hanging fruit for environmental education. Ospreys are large and exciting birds. They are often heard before seen. While they perform their “sky dance” flights they sound off with bracing, high-pitched calls to announce themselves to intruders or to garner attention in courtship. In Ospreyspeak, they are announcing, “See me here, this is my nest, and she is my mate.”

Ospreys mate for life but migrate and spend their winter “vacation” separately. During the breeding season, the males rise up some 30 feet above the water, hover in place for better focus on the fish below, and perform spectacular plunge dives 8–10 times a day, to secure enough fish for themselves, their female mates, and eventually, their young. Females do not catch any fish for nearly 5 months while they are in their nesting and motherhood phase. Ospreys coexist with humans unusually easily, preferring to erect their impressive stick nests on structures like man-made platforms, ship masts, electrical poles, cell towers, and bell buoys. The nesting cycle can be witnessed in full view from the shoreline or from a boat. Taking time to sit on the shoreline and simply observe the ancestral benchmarks of fish hawk reproduction is a treat for any age.

Osprey drawing from Getty Images, Andrew Howe

With a child at your side, there are many entry points to begin the process of inquiry and excitement. Adults can set the stage for anticipation. Guess the date of the first Osprey sighting. Hint: male birds almost always return first to Connecticut coastal marshes March 19–24. That is a good time to set up an Osprey calendar. Become a nature detective and witness nest site selection, courtship, nest building, incubation, chick emergence, fledging, and migration. Observe it, track it and have fun! Identify one or more nest platforms to adopt and return to as often as possible to take mental or real field notes with photography, drawings, and written descriptions of breeding bird behavior. It helps that Ospreys prefer to remain loyal to their particular nest year after year, which has the advantage that the work of nest building is already accomplished but with considerable repair work often necessary after the ravages of winter.

When the females return a few days later, suddenly there will be two active birds virtually tethered to the platform. For the most part, the soon-to-be Dad birds will be busy gathering hefty sticks, one at time, to build or enhance their nests. Children can scatter large sticks on the ground nearby for the Osprey to snatch up on their homebuilding forays. It won’t be long before egg-laying occurs in early May and two to three chicks pop up above the mass of woven sticks five weeks later. Hunting and fish delivery activity are now in full force with downy chicks ravenous for protein. After about 50 days of watching and waiting in the nest, young Ospreys with sturdier feathers are nourished enough with a diet of daily fish that they attempt their first awkward flights, just like children with their first steps. Once the young are independent and airborne, Mom Osprey leaves the roost to regain strength and head south. Meanwhile, Dad Osprey continues his fish forays back and forth from the nest to supplement the diet of his fledglings. Neither parent teaches their offspring to hunt fish, which becomes an inefficient trial and error survival test for each fledgling. By early September, our Connecticut River Ospreys start heading south with the first-year birds trailing in the subsequent weeks. It is probable that this family group will never be united again. They disperse on their own and fly solo over 3,000 miles south on an epic and arduous monthlong migration. They have strong memories for the visual cues of stopover feeding areas and usually forage along the Atlantic coastline, Haiti, and Cuba before ultimately reaching South America, often as far as the Amazon Basin. Satellite transmitters placed on migrating Ospreys show that they navigate these long distances with uncanny precision, especially when travelling over open water like the Caribbean Sea. They never rest on open water, perhaps orienting to varying intensities of earth’s magnetic fields. Scientists also project that Ospreys use the position of the sun and stars as navigational aids.

Observing Osprey breeding season events from chilly March until balmy September is to witness about as clearly as humanly possible, the primordial cycle of life, as seen through the lens of an iconic and dramatic estuary bird. Happy Osprey-ing!

Eleanor Robinson grew up on the shores of Long Island Sound in the neighborhood of the Cold Spring Harbor Biological Laboratory and was indelibly influenced by the nearby estuary and sand spit as well as the lectures and programs of lab scientists and educators.

She graduated from the University of Washington in Seattle where she was a work/study student with jobs including field work for the University’s Burke Museum of Natural History, the Provincial Museum of British Columbia, and for a PhD student writing the Catalogue of Washington Seabird Colonies.

Eleanor earned a Master’s degree in Science Journalism and a graduate certificate in nonprofit management. She has worked as a teacher and writer for Tabor Academy, the Massachusetts Audubon Society, the Denison Pequot Nature Center, and the Science Center of Eastern Connecticut. Her most recent position was that of founding director of Connecticut Audubon’s Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center serving Southeastern Connecticut and focused on the Connecticut River Estuary.

Some Osprey trivia to share at strategic times with a young one at your side:

♦ Osprey females are significantly larger than males.

♦ Ospreys are the only raptor that feed completely on a diet of live fish.

♦ Ospreys mate for life and return to their nest site year after year

♦ Ospreys are a global species and nest from Australia to Japan, Europe to Canada and the USA

♦ Ospreys are one of the few large birds that hover

♦ Ospreys have naked legs and especially long, curved and sharp talons. The bottom of their feet are covered with rough spines—all adaptations for seizing fish.

♦ Osprey adult birds have a yellow iris. Younger birds have orange-red eyes.

P.S. For more information and enjoyment, learn more through the Connecticut Audubon Society Osprey Nation program. View the live stream Osprey Nation “Osprey cam” on the nest. Maybe you and your family members will be motivated to become official Connecticut Audubon Osprey Stewards. Check out the migratory routes of individual Ospreys equipped with transmitters and tracked by satellite on Rob Bierregaard’s website ospreytrax.com and described in his children’s book, Belle’s Journey. Also recommended is the recently published book of Dr. Alan Poole, Ospreys, the Revival of a Global Raptor.

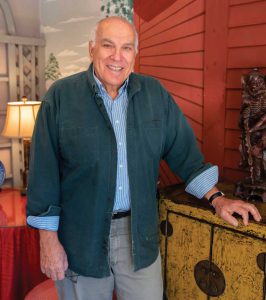

A Room With a View

By Rita Christopher

Photography by Jody Dole

Tom Rose does not live on the Connecticut River, but he lives surrounded by a panoramic River view. His view is not obstructed by buildings, by trees or by traffic-laden roads because he created it himself.

Rose, an artist, painted a large mural of the River along a wall of his antique shop, Black Whale Antiques at Rattleberry Farm in Hadlyme, CT. The mural depicts the River as it might have looked in the mid-19th century at the site of the Chester Ferry. The ferry landing itself is just over a mile from Rose’s shop. The mural includes boats, both steam and sail, among them the most famous steamboat on the Connecticut River in the 19th century, The City of Hartford. It came into service in 1852, though it is best known for a spectacular accident in 1876. On a run from Hartford to New York City, the steamboat plowed into a railroad drawbridge at Middletown. The City of Hartford remained immobilized for four days while wreckers separated the steamboat from the debris of the bridge but it was not the end of the City of Hartford. Renamed Capitol City, the steamboat continued travelling the River for ten years after the accident until 1886.

Rose painted the mural about a year and a half ago, and since then has done at least ten more for various clients, sometimes including boats belonging to the people who commissioned the painting.

“I like what a mural does to a room,” Rose said. “It adds depth of interest.”

Rose, who displays his own paintings along with the antiques in his shop, also does maritime scenes, which he describes as done in the manner of 19th century English artist James Buttersworth, who lived for many years in the United States. Some of his most famous works, in fact, are of early America’s Cup races.

Rose, who displays his own paintings along with the antiques in his shop, also does maritime scenes, which he describes as done in the manner of 19th century English artist James Buttersworth, who lived for many years in the United States. Some of his most famous works, in fact, are of early America’s Cup races.

Rose said his own maritime scenes are larger than Buttersworth’s. “I paint in Buttersworth’s style, but I blow him up,” Rose said. Size is not the only difference between the two artists. “Buttersworth will cost you a couple of hundred thousand dollars, at least. You can get mine for a lot less,” Rose said.

Rose’s art encompasses another completely different genre, humanized animals that combine realism and whimsy to notable effect. The first animal portrait he did was a Jack Russell terrier dressed in a naval uniform; the dog is now known as Admiral Jack. Another of Rose’s creations is a clumber spaniel, a breed with a sturdy and substantial build, dressed as a solidly respectable English gentleman.

Rose sometimes paints animals as canine versions of famous portraits. John Singer Sargent’s well-known portrait of Madame X, a long-necked beauty in a black dress, is transformed into the graceful lines of a whippet shown in the very same black evening gown, and a snub-nosed pug with a pearl in its ear is the canine version of Vermeer’s famous Girl with a Pearl Earring.

Rose sometimes works from pictures taken by the pets’ owners. “I tell them to get down to the dog’s level and photograph eye to eye,” he explained. Because Rose has done the anthropomorphic canines for so many years, he has had time to observe both the pets and their owners. “It’s amazing how much dogs can look like people,” he said.

When Rose bought Rattleberry Farm for his shop and studio, friends advised against it. “They told me it was the middle of nowhere, but I bit the bullet and it has worked out well for me,” he said. Now, however, the complex is for sale, and Rose would like to move back to the Farmington area where he grew up. But he doesn’t have to abandon his view of the Connecticut River. He can always paint the mural again on another wall.

Rita Christopher is a free-lance writer who has lived in Connecticut near the mouth of the Connecticut River for 40 years.

A dreamed of trip becomes a reality— paddling down our Connecticut River

Bald Eagles of the Connecticut River

A Status Report on the Bald Eagle in the Connecticut River Watershed

By John Buck

photograph by Frank Dinardi

sketch by Bruce Macdonald

Dead drifting my canoe along a stretch of the upper Connecticut River a few miles upstream of the Wilder Dam, a flash of white against the dark green pine background revealed the perching spot of an adult Bald Eagle. I had been receiving credible reports of a pair of eagles in the area and wanted to see if I could confirm a nest or at least a territorial pair. Remaining motionless for fear of flushing the bird, I waited in hopes it might reveal a second adult or even a nest. Eagle nests are unusually difficult to spot by themselves, despite measuring as much as six feet in diameter and weighing several hundred pounds.

Dead drifting my canoe along a stretch of the upper Connecticut River a few miles upstream of the Wilder Dam, a flash of white against the dark green pine background revealed the perching spot of an adult Bald Eagle. I had been receiving credible reports of a pair of eagles in the area and wanted to see if I could confirm a nest or at least a territorial pair. Remaining motionless for fear of flushing the bird, I waited in hopes it might reveal a second adult or even a nest. Eagle nests are unusually difficult to spot by themselves, despite measuring as much as six feet in diameter and weighing several hundred pounds.

The upstream breeze counteracted the River’s current allowing me to remain in place for nearly an hour. A second bird never appeared and whether the eagle decided I wasn’t worth the risk of remaining, or it was hungry, or simply wanted to see more of the River, it flew off to the north. With a mighty push of its legs, shaking the pine bough as it released its grip, and a few deep powerful strokes of its six-foot wingspan, the eagle was soon out of sight. Though I had seen many eagles over the years, my feelings of awe and inspiration were just as profound as my first encounter so many years ago. It is no wonder the peoples of the Wampanoag, Pequot, Abenaki, and Quinnipiac, were among the many first Nations to revere the Bald Eagle and place them highly within their tribal rituals and customs.

Ever since the Continental Congress officially adopted the eagle in 1782 as our nation’s national symbol, the species has had a remarkably difficult existence during the past 200 years. Habitat loss due to extensive land clearing and polluted waterways, popular fashion using wild bird feathers, persecution, and later, the introduction of DDT into the food chain resulted in an estimated population of less than 500 nesting pairs in the lower 48 states by the 1960s. And, no nesting pairs were found in the Connecticut River basin as recently as 30 years ago. In fact all of New England was void of nesting Bald Eagles except for some of the coastal and more remote habitats of Maine.

Through public awareness and laws,

habitat quality steadily improved to the

point where eagles could find suitable

nesting and feeding habitat.

Today’s eagle population is a different story. There are an estimated 10,000 nesting pairs in the 48 lower states including at least 50 pairs in the Connecticut River basin. Through public awareness and laws such as the Migratory Bird Treaty ACT (1918), the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (1940), the Clean Waters Act (1972), and the Endangered Species Act (1973), habitat quality steadily improved to the point where eagles could find suitable nesting and feeding habitat. These actions and the banning of DDT in 1972 allowed for the growth and resurgence of Bald Eagles throughout the land. So well has the eagle population recovered that it was removed from the federal endangered species list in 2007. This success story is being repeated in the Connecticut River Basin, too.

The lower part of the River was first to experience the eagle’s return. First to have eagles disappear from the state, Massachusetts last recorded nesting eagles in Sandwich in 1905. But from 1982 to 1988 the state undertook an aggressive effort to reestablish a nesting population by importing orphaned eagle chicks from the Great Lakes region of Michigan and neighboring Canada. The transplanting work centered on the Quabbin Reservoir where, during the six-year reintroduction, 41 eaglets were raised to adulthood, and by 1988, Massachusetts had their first nesting eagles in 83 years. Success at Quabbin extended beyond its borders to include 11 pairs along the Connecticut River by 2018. Eagles are a regular sight along the River in Massachusetts. Turner’s Falls (Greenfield) and vicinity has proved popular for nesting eagles. So well have the eagles faired in Massachusetts that the state has proposed the species be down-listed from threatened to a species of special concern.

Farther downstream, Bald Eagles have experienced similar success. Sharing the story of the eagle’s perilous decline with the other Connecticut River states, Connecticut was fortunate to retain a modest residual population of wintering eagles along its lengthy Long Island coastline, especially at the mouths of major rivers like the Connecticut. But, in 1992, a pair of eagles successfully reared two chicks in Litchfield County. Since then the state’s eagle population has steadily grown to where the state downlisted the eagle population from endangered to threatened in 2010. Connecticut’s eagle population continues to expand and by 2018, state biologists estimated between 50–55 pairs to be residing in the state. Although winter continues to be the best time to view eagles in towns such Haddam and Essex, tributaries of the Connecticut like the Scantic River in Sommersville and Shenipsit Lake in Ellington also support a feeding habitat and potential nesting territories as well as offer viewing opportunities.

Getty Images, Mariusz Stanosz

Vermont and New Hampshire have shared a long and interesting history together. Beginning with the fact that, while New Hampshire was one of the original 13 colonies to form the United States, Vermont (once named New Connecticut) remained as an independent nation from 1777 until 1791 when it was admitted to the union as the 14th state. That subtle but important difference is still played out in many things today including Bald Eagle restoration. The difference is due to the fact that 90 percent of the River between the two states belongs to New Hampshire. The eagles, however, don’t know that, nor do they care. Eagles on both sides of the River hunt the River’s tributaries in both states. The only boundary lines they are concerned with are those established by the eagles themselves. Like so much of the habitat in Massachusetts and Connecticut, reforestation along the upper reaches of the River is, once again, an excellent eagle habitat.