Walking through the Connecticut River Valley woodlands in the autumn, you might happen upon a large understory plant with gentle golden star-flowers and few leaves, a strange anomaly this late in the year. This is witch hazel, sometimes called spotted alder or winterbloom, and grows throughout New England, appearing to be a large, irregular shrub or small tree.

Land Trusts in the Watershed

Land trusts as a mechanism for preserving land for public use have existed for thousands of years. However, most land trusts in the United States established for conservation purposes were created after World War II, starting in the 1960s and 1970s, and continuing today.

From the Publisher:

My wife and I had just spent the night in a tent high up in the Tien Shan Mountains of eastern Kyrgyzstan, just down the road from where the Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin

prepared his physique for space flight.

A Magnificent Obsession: Our Fascination with Wildlife (Part 1)

One theory of our fascination with animals holds that we observe them, in their native habitats and in zoos, to discover deep origins of our current behavior. In short, we view animals as reflections of ourselves and we watch them to learn more about us.

Invitation to Public Comment Meeting for the Proposed Connecticut National Estuarine Research Reserve

You are invited to attend a virtual public comment meeting for Connecticut’s proposed National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR).

The meeting will be held on Tuesday August 4th, 2020, from 7:00 to 9:00 PM EDT via WebEx.

Become an Environmental Activist (Part 2)

Last time, we parted with my advice to first become informed about the state of the environment and then develop the conviction that you can make a difference to the environment by volunteering in an area that interests you.

If you are still left wondering what you can do, you can start your involvement by looking no further than your personal lifestyle, back yard, or neighborhood.

Become an Environmental Activist

I started to write this blog on the topic of citizen science for the Connecticut River environment but soon realized that the concept could be too narrowly interpreted as just “science.” To be clear, citizen science usually involves a collaboration between non-scientists and scientists in which non-scientists collect data needed by scientists to resolve real-world issues.

Solving Environmental Problems

Environmental problems can be complex and hard to resolve. The complexity arises because the components of the environment are linked, and their interactions may be separated by both time and distance.

The Connecticut River’s Tranquility

In these times of stressful living, designed to contain the coronavirus, more and more people are seeking solace in nature. The fall 2020 issue of Estuary magazine contains several personal essays on this topic.

From the Publisher:

I’ll not dwell on the wonderful testimonials to the first issue…only to say they were as intimidating as they were gratifying as we realized how this second issue, with its theme of recreation, would be measured against the first. Once again, we count on our readers to tell us how we did, and always, how we can do better. We also look forward to submissions of articles and photos through our website at estuarymagazine.com.

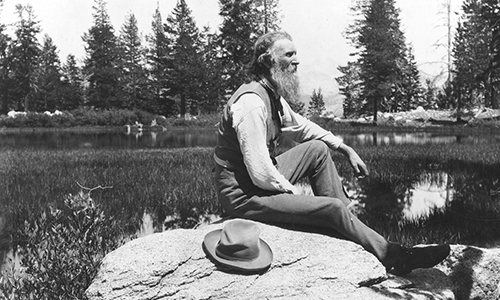

Editor’s Log: Island Solitude

“Come to the woods, for here there is rest,” wrote John Muir, the pioneering environmental activist and writer. “There is no repose like that of the green deep woods.” Few knew the healing power of nature better than Muir (1838–1914), whose deep connection with the outdoors was forged through a convalescence.

Vermont Center for Ecostudies

SPONSORED CONTENT

Just about a mile as the crow (or cardinal, or chickadee) flies from the Connecticut River’s western bank in Norwich, Vermont, sits a nondescript building that houses one of the most effective wildlife conservation organizations in the Northeast that

you’ve probably never heard of: the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE).

Watery Wilderness

The Connecticut River meanders for almost 200 miles from north to south along the entire border between Vermont and New Hampshire. It’s a gentle river, beloved by paddlers of all abilities for its unspoiled shoreline, abundant wildlife, and ample public access points.

Improved Clinch Knot

Step-by-Step Instructions

My Love Affair With Kayaking

When I was nineteen, I moved from Texas to Massachusetts to attend Hampshire College. I had lived my whole life up to that point in a hot, flat landscape, so when I moved North, I wanted to get to know the landscape as intimately as I could.

Where Have All the Birds Gone?

A recent study by Cornell University found that there are nearly 30 percent fewer birds in North America than there were in 1970

A Rude Awakening and Call to Action

This fall, scientists at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology spearheaded a sobering report, “Decline of the North American Avifauna,” Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.aaw1313 (2019), that forces us to moderate our pride in environmental regulations at home.

Take Me Fishing!

Can you take me fishing?” If you are a parent who fishes, that request from your child may prompt the proverbial happy dance. Most anglers pray that their kids will follow in their waders. However, if you can’t tell an improved clinch knot from a Windsor, or a yellow perch from a bullhead, you probably would rather be asked where babies originate.

Verse

A Kipling classic.

Who Owns the Connecticut River?

Our Connecticut River has a storied past—especially the struggles between contenders for who owned the River. As one of our most discernible landmarks flowing down the center spine of New England, the River was referenced as a boundary of the various states beginning as early as 1644 with kerfuffles lasting nearly 300 years.