It would be hard to proclaim which plant wins as the worst terrestrial invasive species in the US, but Japanese Knotweed, Polygonum cuspidatum, is a clear contender.

What’s for DINNER?

Lamb vs. Mutton

They are both domestic sheep…but hardly interchangeable.

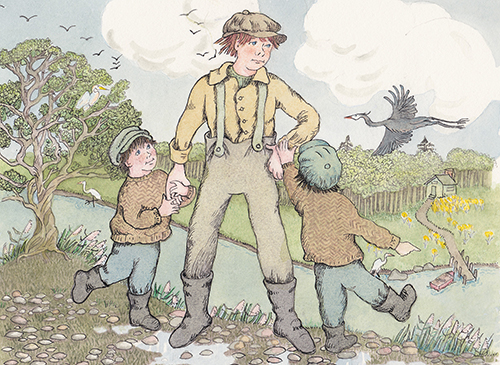

Tales of a Connecticut River Ferryman’s Son

I put my hand out in front of me like I’m offering to shake and say: “How do you do, sir. I’m called JJ, just like my father, and his father, and his father before him. We’re all ferrymen here in Old Saybrook, and we’re all called JJ.”

Last of the Legendary Watermen

Oliver LaPlace was born on the Connecticut River, almost. The family homestead in Lyme backed up to its eastern shore. They had to keep a close watch on young Ollie, especially during the spring freshet. He was drawn to the water something fierce.

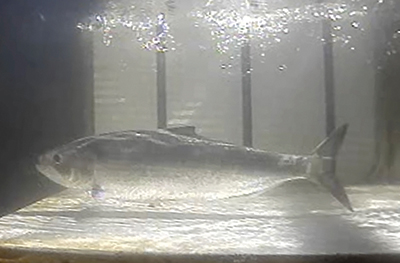

Up and Over, Clearing Obstacles to Reach Habitat

Historically, each spring throngs of migratory fish from the ocean surged up the Connecticut River and its tributaries as far inland as they were able.

Hydropower

We are publishing two articles about the hydropower industry in this issue of Estuary. The first offers an overview of, or a peek at, the hydropower industry, an important but largely behind-the-scenes stakeholder in the Connecticut River watershed.

Dams, Fish, & Relicensing Major Power Plants

Believe it or not, there are more than 3,000 dams on the mighty Connecticut River and its myriad tributaries.

Loons

I saw my first common loon in January of 1958, at the mouth of the Connecticut River. In those days, Griswold Point was connected to the mainland. As a twelve year old, on my own, I could hike dry-shod to the point’s end and survey the River’s mouth.

Colt

Heading up the Connecticut River, just below downtown Hartford, the west bank reveals an incongruous vision. Eyes are pulled to a blue, onion-shaped dome, spangled with golden stars and tipped with a rampant colt finial.

Crossing the Bar

There’s a sailor superstition about changing a boat’s name. State of New York, largest and costliest steamer ever to run on the Connecticut River, was to be called Vermont.

Moose

Moose comes from the Algonquin word Mooswa, meaning “the one who strips twigs.” To fulfill its life functions, the North American moose, Alces alces, requires some 10,000 calories per day, equating to between 50 and 100 pounds of food.

About Our Blog:

In case you missed it, our luscious website (estuarymagazine.com) also features a blog.

From the Publisher:

This issue of Estuary contains our first article by a descendant of Indigenous people. These people inhabited North and South America for thousands of years, maybe 12,000 years, long before the word “America” existed.

The Elusive Bobcat

Meet the bobcat, an elusive, captivating animal that is prevalent in the Connecticut River Valley, yet one that many of us—myself included—have rarely seen in the wild.

What’s for Dinner?

Pekin Duck and Peking Duck are wildly different! Peking Duck is the cooking preparation and presentation of a duck dish originated in Peking (Beijing), China, during the Imperial era and is still popular today.

Your Best Shot

“Sunset Over the Connecticut River”

Photo by Susanne Hall

The Falls

A poem by David Leff, an award-winning essayist, poet, and former deputy commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection.

Hydrilla

By now, knowledge that invasive plants are bad news is pretty widespread. Numerous articles and agencies cite “billions of dollars” in damages annually to agriculture and fisheries; they are the “leading cause” of population decline and extinction in animals.

Turners Falls Area Winter Birding

In March 2019, a flock of 20 tundra swans made an unexpected overnight visit to a historic canal at Turners Falls, Massachusetts, one of the Connecticut River watershed’s finest winter birding destinations. The swans, which breed in the Arctic and overwinter on the mid-Atlantic coast and other regions, delighted fortunate observers before departing the next morning.

Introducing a Regular Column About Migratory Fish in the Watershed

Some of the most historical and ecologically-significant migrations of the Connecticut River are missed by most. These are the annual migrations of fish—specifically diadromous fish.