We weren’t settled for very long in Glastonbury before I joined the Connecticut Audubon Society and became a member of the Regional Board of Directors of its nature center in Glastonbury and then was elected to the state Board of Directors. These responsibilities introduced me to still more dimensions of the Connecticut River. Volunteering at the Eagle Festival, which the Society used to host as a major fundraiser toward the end of winter each year, brought me in contact with the charming village of Essex, which I quickly grew to adore—a liking born of the scenic bicycle ride along the Connecticut on River Road, the breathtaking view to the east across the River, the Connecticut River Museum, and the choice of very good restaurants in town.

I fondly recall one festival day when the temperature didn’t rise above 0° F. We froze on the ferry that was plying the river in search of eagles; despite the cold, we spotted 17 bald eagles and one golden eagle. Afterward, we warmed up at the Griswold Inn with a steaming bowl of their gourmet New England clam chowder while seated beside a crackling fire in the Inn’s colonial-era fireplace.

Another allure of Essex is the steam train that chuffs and whistles along the River pulling restored Pullman cars and, as an option, off-loads passengers for a 2-hour boat ride on the Becky Thatcher up and down the River. We’ve also taken our grandkids on the train ride option that drops passengers off at the road (Route 148, Ferry Road) to the Chester-Hadlyme Ferry and gives travelers enough time to cross the river on the ferry, hike up the trail to visit Gillette Castle, eat a picnic lunch, and make their way back to the return train. The vista of the Connecticut River seen while standing on the Gillette Castle’s porch is nothing short of spectacular.

Vista of the Connecticut River as seen from Gillette Castle.

When I was chairman of the Connecticut Audubon Society’s Board, one day I received a call to meet with some citizens in the town of Old Lyme, across the River from Essex. This amazingly talented group had a vision to establish a nature center in Old Lyme that would focus on conservation research, environmental education, and artwork of subjects in nature. (For those who don’t know, the bedrock of Old Lyme’s culture is art; the town is home to The Florence Griswold Art Museum, The Lyme Academy of Fine Arts, The Lyme Art Association, an art gallery, and a sculpturing studio. Old Lyme was also the home of Roger Tory Peterson, who was a prolific painter of birds and published bird and other wildlife field guides made popular by the simplified identification techniques that he devised. An article about him is planned for the Fall 2020 issue of the magazine.)

The group wanted to explore joining the Connecticut Audubon Society as its nature center in southeastern Connecticut. I caught their enthusiasm and became a champion of their cause, which came to fruition four years ago as The Connecticut Audubon Society’s Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center (RTPEC). Early on the founders of RTPEC had solicited the help of the Mentoring Corps for Community Development (MCCD), a collection of very capable people, mostly retired (much like Encore), who have the mission to assist individuals, small organizations, and whole communities solve problems and develop strategies for sustaining themselves. Together, RTPEC and MCCD became sources of new friends and challenges, particularly with respect to the River.

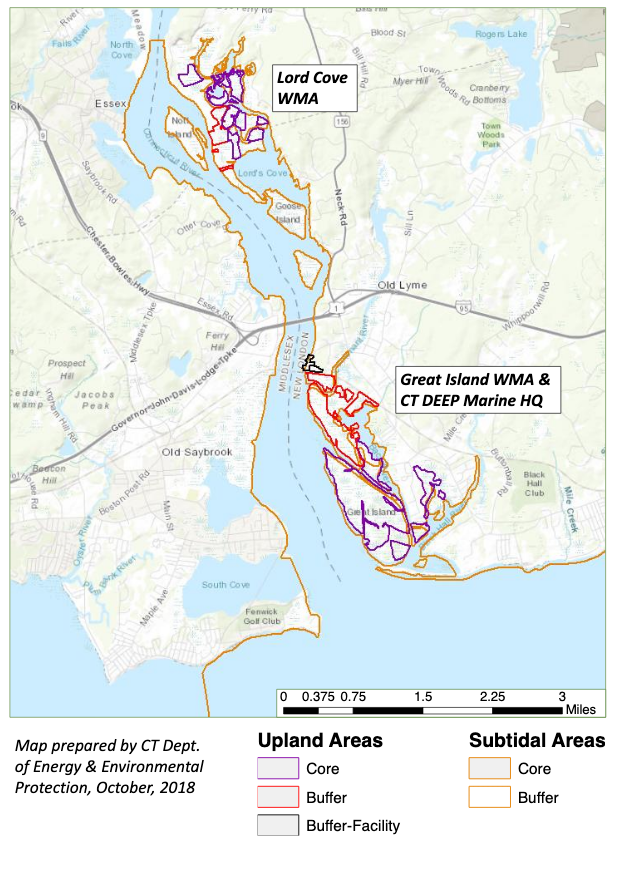

My activities with RTPEC led to my membership, with its board’s vice-chair, on a team responsible for justifying and selecting a site for a proposed National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) in Connecticut. Led by Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP), our team’s two-year effort culminated with a site recommendation that has subsequently been approved by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which oversees a system of 29 NERR sites in coastal states across the country, including Hawaii. In the northeast region there are already NERRs in Maine (Wells), New Hampshire (Great Bay), Massachusetts (Waquoit), Rhode Island (Narragansett Bay), and New York (Hudson River). Connecticut’s NERR promises regional benefits in the areas of conservation research, environmental education, training for coastal decision makers, and environmental stewardship.

Of particular value is the NERR system’s extensive library of knowledge, applications, tools, techniques, and education and training programs for environmental issues facing estuaries and wetlands. The library holds the results of a large number of projects that were undertaken system wide. In the northeast sector, about 12 projects involve science collaborations among several NERRs that are facing common environmental challenges (i.e., climate change, sea level rise, shoreline stabilization, wetlands and other habitat preservation, endangered species, water quality).

To complete the designation process for Connecticut’s NERR, RTPEC and the Connecticut Audubon Society are now working in collaboration with NOAA, DEEP, and the University of Connecticut on developing a management plan and an environmental impact statement for this site, which includes part of the lower Connecticut River and an eastward stretch of Long Island Sound. Look for more details about Connecticut’s NERR Site in the Fall 2020 issue of Estuary magazine.

Proposed CT National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) site map- Western areas.

For me, working on Connecticut’s NERR site selection and designation teams has been both a labor of love and an extremely rewarding experience in building my knowledge of the Connecticut River and the organizations and people that call it home.

One day I was talking with Dick Shriver, whom I had met at MCCD and partnered with to deliver enrichment sessions to classes at the Bennie Dover Jackson Middle School in New London. We were discussing the large number of organizations and interests that exist along the entire length of the Connecticut River—soon to be joined by the CT NERR. The idea of a magazine, to be a focusing voice and vehicle of collaboration among these various interests, suddenly struck us. Finding nothing extant that would meet our concept for such a voice, we initiated the planning and designing of Estuary magazine together with a business and marketing strategy.

The first issue demonstrated that our team of talented writers, editors, photographers, graphic designers, and media and printing professionals can produce a high-quality product that is a credit to the beauty of the River and its watershed. I believe that where we go from here, as I hope that I have illustrated in my story, will depend considerably on the depth of the emotional commitment and affection—love—that our readers either have or will develop for the River.